The American Marketing Association defines a brand as a “name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers.” While this shorthand definition is convenient, it completely misses the inextricable mental associations and emotional linkages that consumers create when valuing brands.

On the continuum from cave paintings to social media updates, symbols have created an infinite sensory palette of visual and verbal expression which instantaneously produces the intended perceptual recognition – belonging, love, respect, loyalty and advocacy.

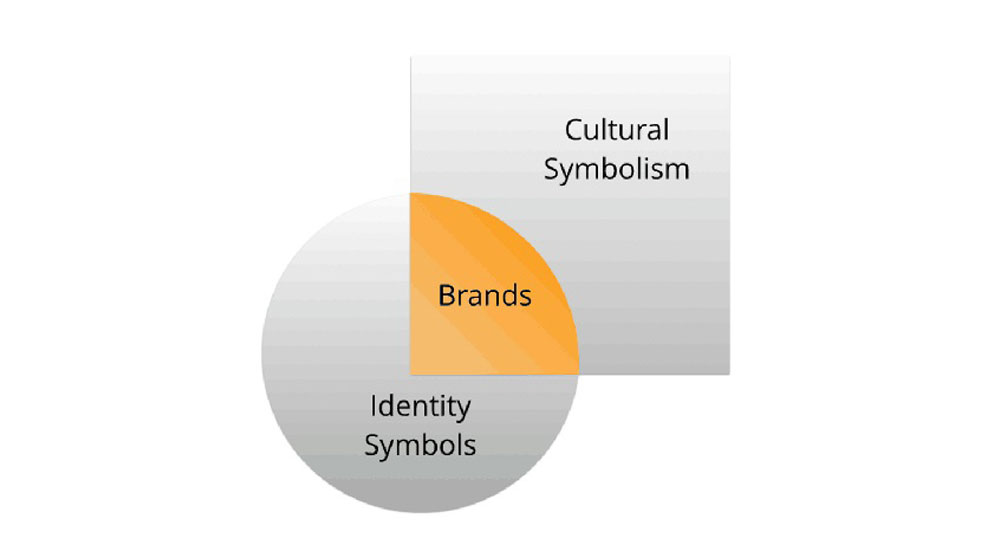

Brand identity elements, from names to tags to designs, are only the material markers completely devoid of meaning. It is often the case not what the brand stands for, but what consumers perceive the brand stands for. If a consumer is intimately attached to a symbol, close examination divulges that there is actually less to the symbol than meets the eye. A wedding ring does not mean a marriage has occurred. For instance, the bride from the Syrian Christian communities of Kerala wears minnu (a pendant) to signal marital union. Should we apply principles of cultural anthropology to advance branding from mere material symbols to the realm of symbolism, a collective understanding of the plots and metaphors that spur customers’ imaginations and mental associations begin to be defined.

Symbolism is a culturally-determined activity, more as a totality than as the arithmetic sum of a group of symbols. In branding, the object of symbolism is the enhancement of the importance of what is symbolized. This enrichment to symbolic meaning occurs when brand stories are recited by various authors: Company, culture intermediaries, critics, retail sales personnel and customers.

SEE ALSO: Patagonian Toothfish or Chilean Sea Bass: Names Matter, Especially Internationally!

I spent three years pursuing a ‘going native’ type of interpretive ethnographic research on customer evangelists who pompously wore a brand logo as a tattoo. Harley Davidson loyalists don’t care about the torque generated by the engine; rather, it is the Harley brand values espoused by sociocultural, symbolic, and ideological aspects that transform the casual biker into a Harley loyalist. In fact, many car buyers ignore and/or are completely ignorant of product attributes and technical specifications, such as a multi-point fuel injection system, the engine compression ratio, etc. None of the brands are found in lists of attributes, nor sets of form and function. Instead, brands can be known only by the unfolding of their unique stories within the context of the symbolic perception they create and manage for long periods of time.

When we look at brands through a cultural anthropological lens, it becomes more discernible as to why consumers tattoo themselves with the Harley Davidson or Nike logo in permanent ink to proudly claim membership of a tribe; sprinkle the rim of a Corona bottle with sea salt and insert a lime wedge to flavor the beer; never mind paying $2.59 for a cup of Starbucks when they can brew coffee at home for $0.07/cup. As we move into the consideration of symbolic perception, our concern with fields, organizations, and relationships shifts our framework of brand discourse to approach brands as vessels of symbolic meanings that evoke personalities and emotion through myth, rituals, symbolism and ethos.

Brand is a noun. It is a verb. It may be about what we do. But, overall, it is all about what is in the mind – the mind of the consumer and the mind of the employee. Regrettably, most books, articles, and practices (like AMA’s imprecise definition of a brand) approach, analyze and articulate brand as a mere material marker from a business economic perspective. It is about time that we start examining brands and branding from a cultural perspective. And anthropology can amply help.