Sometimes a piece of thinking arrives that forces an industry to re-examine its foundations. Thomas Marzano’s new manifesto, Brand Constitutions: The Legible–Lovable Standard for Building Equity in an Agentic Economy, is for me such a moment. Published only recently, its implications are already resonating. For the first time, someone has articulated what it means to build brands in a world where intelligent agents will mediate a significant part of discovery, consideration, and experience. The moment I read it, it connected immediately with a concept that has played a foundational role in my career.

For years, my perspective on brand building has been anchored in the idea that meaning and emotion are what give brands their lasting power. This belief was formed during my years at Saatchi & Saatchi, carrying forward the thinking of Kevin Roberts and his bestseller Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands. For a long time, this book was my branding bible. At its core lies a simple but enduring insight: Brands become “Lovemarks” when they earn both love and respect.

Thomas Marzano reframes this idea for a fundamentally different environment. As intelligent agents begin to shape how people navigate choices, brands must now speak to two audiences simultaneously: the human beings whose hearts they want to win and the intelligent systems acting on those humans’ behalf. This will no doubt influence how branding is practiced.

While reading Marzano’s manifesto and speaking with him in preparation for this article, an urgent question occurred to me. What will happen to “Lovemarks” in this agentic age?

Lovemarks revisited

Before we can understand what happens to “Lovemarks” in the agentic age, let’s return to where the idea comes from. When Kevin Roberts published Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands, he declared that brands were dead and that the future belonged to those able to become Lovemarks. His point was that brands had become too rational, too functional, and too easily commoditized. Lovemarks was his plea to make brands more emotional, more distinctive, and more deeply rooted in myth, sensuality, and intimacy.

At the heart of Roberts’ Lovemarks philosophy sits the love-respect axis. Respect is the rational foundation, built on performance, reliability, reputation, and consistency. Love adds a deeper emotional layer. It explains why people form deep, often irrational bonds with certain brands while feeling nothing for others. A Lovemark is the union of both—high love and high respect. Trusted and desired. Rationally sound and emotionally resonant. A brand people choose even when alternatives are cheaper or more convenient.

For years, this framework has encouraged marketers to move beyond functional brand building and toward genuine human connection. Great brands are irreplaceable, but Lovemarks are irresistible. This core insight remains valid, even as the world tilts on its axis: brands become meaningful and valuable when they combine consistent, reliable delivery with real emotional resonance.

But the concept of Lovemarks was born in a world where people largely made their own choices. In the agentic age, trust must also be verified by intelligent systems, while love must be strong enough to influence automated and agent-induced decisions. The mechanics of respect and love need to evolve. Love remains essential as respect broadens.

From respect to machine trust

In the original Lovemarks model, respect forms the rational foundation of every enduring brand relationship. It’s earned through performance, reliability, integrity, and consistency—the behaviors that build human trust over time. Without respect, love cannot take root. In a human-led world, this logic is both intuitive and sufficient. People compare experiences, remember how brands behave, and form judgements based on interpretation and context. Trust lives squarely in the human mind.

In an agentic world, that mechanism shifts. Not because respect matters less, but because it now operates in an environment where intelligent systems help determine what becomes visible, what is considered, and what is ultimately chosen. Agents compress the decision journey. They collapse stages that were once human, interpretive, and temporal into system-driven filters. What humans once noticed or remembered becomes a function of pattern recognition and structural clarity.

Systems cannot feel respect; they can only evaluate it. They recognize patterns, verify provenance, assess consistency, and analyze structure. This is precisely what McKinsey describes as the new operating logic of modern marketing systems: not persuasion first, but qualification first, with the system deciding which brands earn the right to enter the field of consideration.

This means that the rational pillar of the Lovemarks model needs a second expression. Not a new idea, but a new form. The substance of respect remains what it has always been—what a brand proves through its behavior—but in an agent-mediated environment, it must also become accessible to systems. Brands must now present their reality not only to people, but also to the systems that increasingly shape and mediate choice.

This is where legibility comes in, meaning the structural clarity with which a brand presents itself to a system. As Thomas Marzano articulates in his Brand Constitutions, brands must not only be lovable to humans but also legible to machines. Legibility isn’t about story or emotion; it’s about coherence, origin, metadata, evidence, and behavioral consistency. People may tolerate ambiguity, but systems treat it as a risk. A brand may be deeply loved by humans yet remain invisible to systems, if its structure is unclear.

This is how respect will evolve in an agentic world. By becoming legible, it will translate into trust at the system level, or what I call “machine trust.” Machine trust doesn’t replace respect; it allows respect to be read. Respect provides the substance, while legibility provides the structure through which that substance can be interpreted. And when a brand’s machine trust is high enough, the system includes it in the shortlist.

Marzano’s manifesto goes on to point at a second implication: Lovability is beginning to leak into the machine. What once appeared to be a purely human, irrational preference is now becoming partially interpretable by intelligent agents. Systems can infer emotional inclination from language, behavioral cues, and recurring choices.

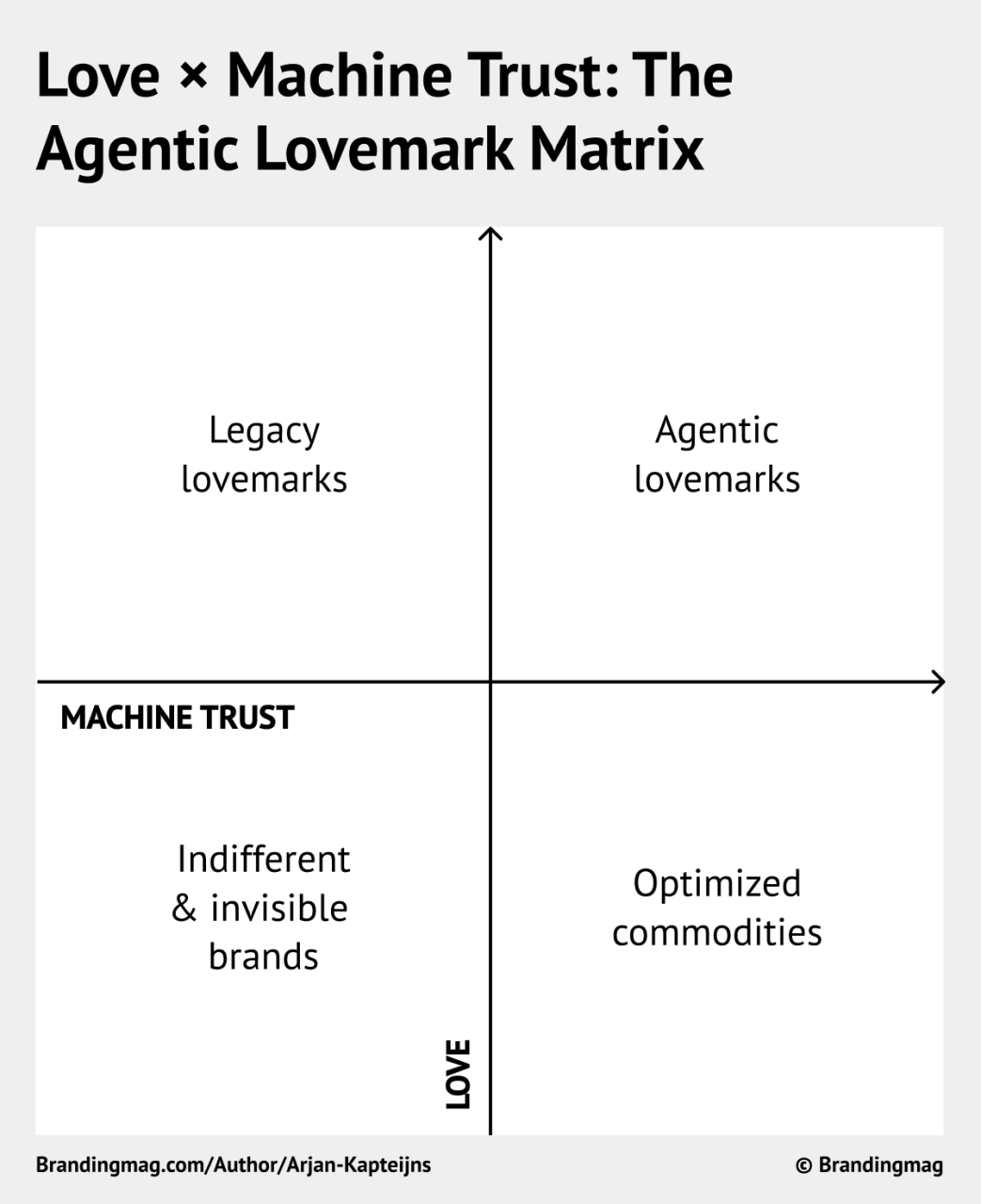

Seen through this lens, love and machine trust form two axes that redefine the classic Lovemarks model. We have the same vertical axis that Kevin Roberts used (love), but the horizontal dimension is expanded from respect to machine trust. This reflects the system-side expression of reliability, clarity, and consistent delivery required in today’s agentic environment.

Mapping love on one axis and Machine Trust on the other lead to four relatively new territories:

- Low love, low machine trust: Indifferent & Invisible Brands

Brands that carry no emotional meaning for people and offer no structural clarity to systems. They fade into irrelevance. - High machine trust, low love: Optimized Commodities

Perfectly legible to systems—efficient and comparable—yet emotionally interchangeable for humans. - High love, low machine trust: Legacy Lovemarks

Brands that earned deep emotional meaning in a human-driven world, but have not yet evolved structurally for an agentic one. As long as love remains alive, these brands tend to trigger human override. If their meaning isn’t translated into machine trust, they risk becoming ghosted over time. - High love, high machine trust: Agentic Lovemarks

The aspiration zone. Brands loved by humans and understood by machines, emotionally meaningful and structurally reliable.

It’s in that upper-right quadrant (the traditional home of Lovemarks) that something new happens. Emotional meaning remains human in origin, yet its signals become patterned and structured enough for systems to recognize, interpret, and act upon. Not because Lovemarks change, but because the environment around them does.

Brands now talk to two audiences—people and agents—at once.

People respond to identity, story, and experience, while agents respond to structure and proof. If you only speak to people, you may be loved but never found. If you only speak to agents, you may be found but never really chosen. The task for modern brand builders isn’t to choose between these logics, but to reconcile them and reinterpret the original love-respect dynamic.

Through that reinterpretation, love remains the fully human dimension of the Lovemarks model, encompassing that which is emotional, irrational, and fueled by mystery and passion. The rational dimension remains respect, but given that the rational judgment is now exercised by both humans and systems, respect now manifests as machine trust in an agentic context. Meaning that legibility is the mechanism, and machine trust is the outcome.

But what will happen when the two collide? If people have a strong emotional relationship with a brand, they probably won’t accept a machine recommendation that ignores said connection. They’ll simply correct the system instead. When I ask an AI assistant to recommend the best car for me, it will utilize performance, sustainability, reviews, and price to return a perfectly rational shortlist. But if my Lovemark BMW is missing, I might just ignore the advice.

This means that, even in a world shaped by intelligent systems, love still will play a role. Because while systems can advise and rank, they still can’t decide what’s emotionally meaningful to someone.

The role of the Lovemark organizing idea

The Lovemarks philosophy evolved in practice, not only in Kevin Roberts’ book but also in the Saatchi&Saatchi method we taught during Lovemarks Academies. And there were effectively three working pillars within it:

- Respect, the rational foundation

- Love, the emotional engine

- The Lovemark organizing idea—the strategic center that brought everything together.

This third pillar became especially important in how we applied Lovemarks. The organizing idea served as the guiding thought of the brand—the principle that aligned strategy, creativity, culture, behavior, and experience. It translated meaning into action and ensured that the brand moved with a coherent sense of purpose.

For decades, many of the world’s strongest brands have been built around a clear organizing idea. Nike was shaped by the belief that athletic potential exists in everyone. Apple grew from the conviction that technology should empower creative individuals through simplicity and human-centred design. Dove challenged category conventions by redefining beauty as something real rather than idealized. In each case, the organizing idea functioned as a strategic compass, aligning product, experience, culture, and communication.

In the agentic era, that strategic center doesn’t disappear. If anything, it becomes more important. The organizing idea must now operate in a dual environment: one shaped by human meaning and one shaped by machine interpretation. It must inspire people while also being interpretable by systems. It must hold emotional depth while offering structural clarity. It must express what the brand stands for while also revealing how it fits into a world governed by metadata, behavioral signals, and machine-driven selection. It’s also the place where love remains fully human, while the behavioral patterns it creates become structured enough for agents to recognize.

This synthesis of love and respect isn’t mere nostalgia for brands of a bygone era; it’s a structural necessity. Brands now operate within “always-on” engines that demand a unifying logic. Without a central organizing principle, these engines fragment brand meaning; but with one, they amplify it.

In this new reality, the organizing idea becomes the bridge between love and machine trust. Love provides the emotional truth, while machine trust provides the structural reliability. Only the organizing idea can unify them into a single, coherent identity. It creates a logic that humans can feel and machines can follow. And when articulated well, it also becomes the essential center of the agentic Lovemark—the force that holds its emotional meaning and structural logic together inside a single, coherent brand ambition.

The Agentic Lovemark

At this point, the pieces come together. Love remains essential, machine trust and legibility become conditional, and the Lovemark organizing idea becomes the operating principle that unites both inside the brand constitution.

What do you call a brand that fosters both human love and machine trust? An Agentic Lovemark.

Be sure to note that this path isn’t limited to brands already perceived as Lovemarks. Some brands inspire love in millions, others in a smaller circle. And many brands are on a neverending journey trying to become a Lovemark. In the agentic era, that journey becomes more structured and necessary.

McKinsey’s recent analyses show that as GenAI compresses the funnel and content becomes increasingly commoditized, emotional distinction isn’t a romantic luxury but a competitive requirement. The more systems optimize the functional layer, the more value resides in the human layer.

Agents aren’t merely calculating what fits but picking up on what resonates. In that light, an Agentic Lovemark is a brand whose emotional preference doesn’t live solely in people’s minds, but also appears as a detectable pattern in behavior, data, and interactions.

In such a brand, the emotional DNA isn’t only claimed in campaigns, but codified into the system in choices, rituals, interfaces, service moments, and data structures. That’s the difference between love as a story and love as a signature. Agents will ultimately not respond to what you say about yourself, but to the encoded traces of the love you’ve actually created.

In a world of automated shortlists and machine-mediated choice, only brands that offer both emotional meaning and structural legibility will consistently surface. An Agentic Lovemark is that brand. It’s a brand with both a soul and a system—a brand that makes people feel something and leaves enough of a trace for agents to pick up on and reinforce.

In other words, becoming an Agentic Lovemark is the new gold standard. Humans choose your brand because it matters to them, and agents choose it because they understand it.

What happens to the banana principle?

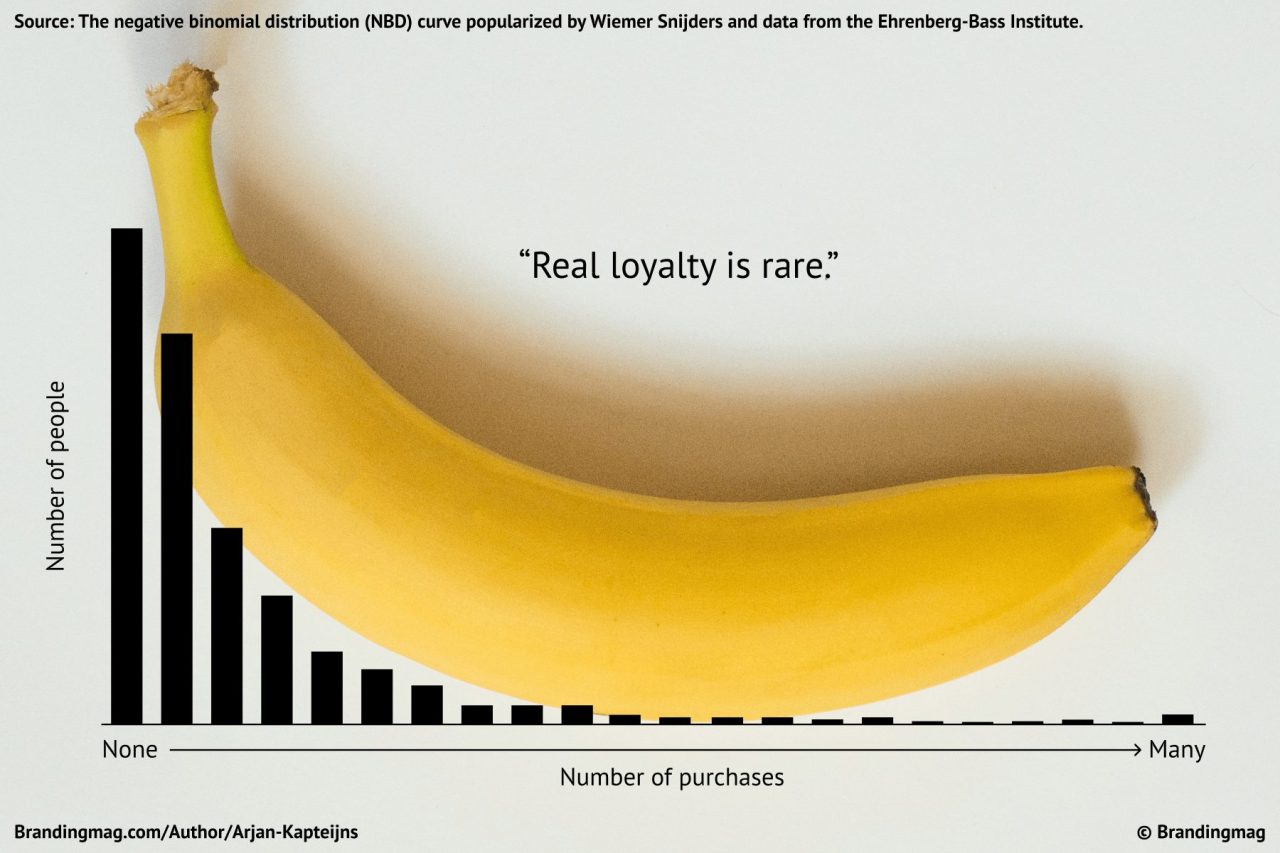

For more than a decade, the Ehrenberg-Bass negative binomial curve shaped how marketers think about loyalty. Byron Sharp states that loyalty is mostly a by-product of penetration and availability. Heavy buyers may look loyal because of buying patterns. Light buyers appear fickle because of statistical distribution. The famous banana principle is the industry’s shorthand to illustrate that real loyalty is rare.

In a human-driven world, that logic might be true for a lot of products and brands, especially in fast-moving categories where people tend to switch. Life is messy. They forget. They get distracted. They grab what’s closest, cheapest, or simply visible.

This behavior (and the entire banana principle itself) stands in sharp contrast to the Lovemarks philosophy, which argues that emotion fuels loyalty and a price premium.

I’ve witnessed this tension up close. Years ago, I saw Kevin Roberts and Byron Sharp share the same stage in Amsterdam. Roberts argued that brand love can lead to loyalty beyond reason. Sharp claimed that loyalty isn’t a growth strategy but a statistical consequence of penetration. Two worlds. Two truths. And, in my view, both are right.

In the agentic age, much of the randomness of past eras will disappear. Agents don’t behave like distracted human shoppers switching their preferences based on random factors. They reduce complexity instead. They stabilize preferences, reinforce remembered choices, and remove many of the micro-moments where switching used to happen.

In a world of agentic mediation, emotional loyalty becomes stronger because brand love is reinforced by the system.

If an agent grasps your preferred coffee, sneaker, airline, or car, and if that preference is legible and trusted, the likelihood of casual switching drops. This doesn’t automatically make people more emotionally loyal, but it does make loyalty more dependable. Love becomes the anchor and machine trust the stabilizer.

What Sharp once described as behavioral volatility will, therefore, become a more consistent pattern and render the banana principle, well . . . less of a banana. Most likely, we’ll see it shift to fewer ultra-light buyers on the left and more stable loyalty on the right. A combination of less randomness and more consistency. A reversed banana diagram, if you will.

How to build Lovemarks amidst intelligent agents

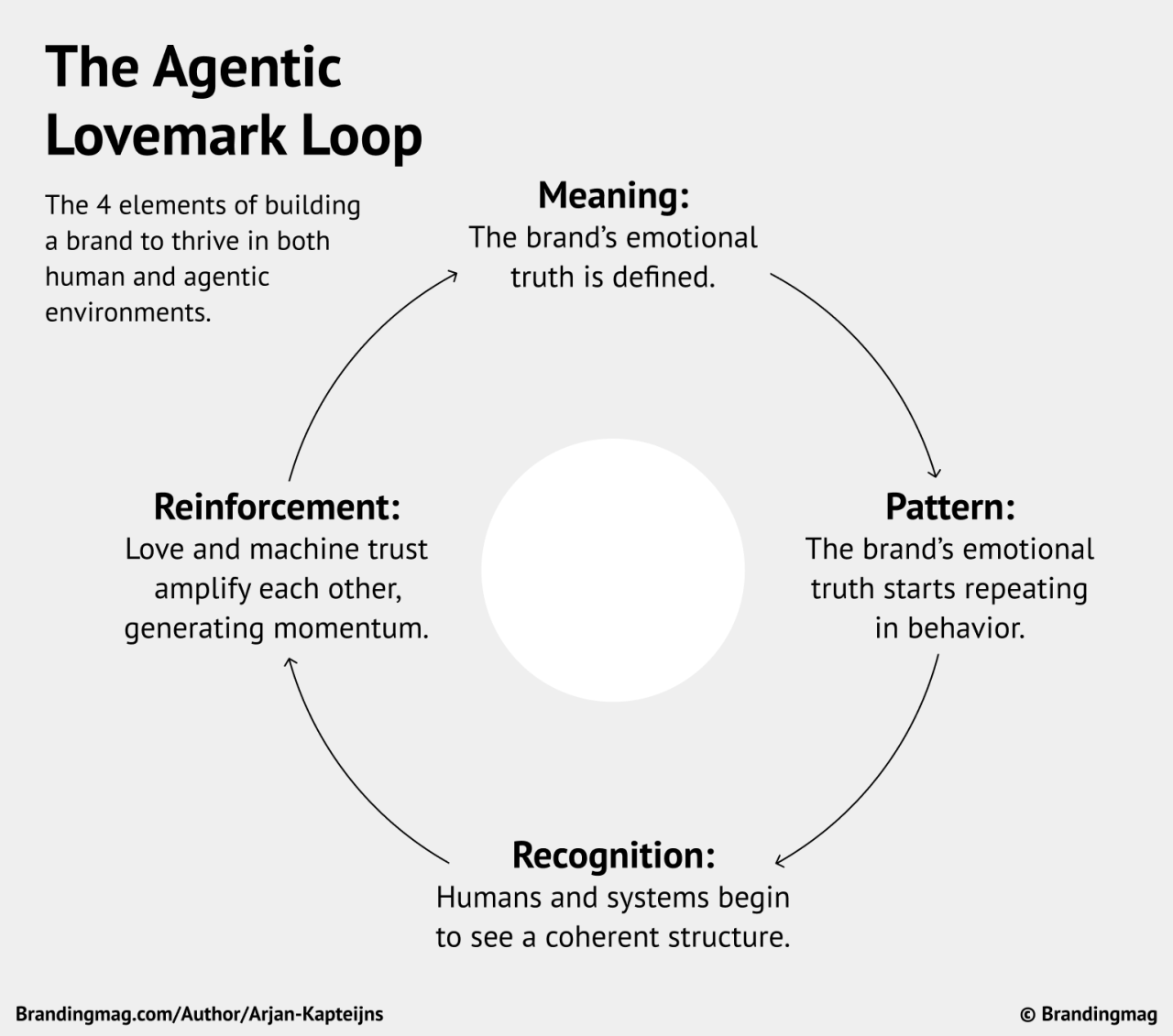

If love sits on the human side of brand choice and machine trust sits on the system side, how do you build a brand to thrive in both worlds simultaneously? The answer isn’t a binary split between emotion and system, but a loop: a self-reinforcing cycle in which human meaning becomes a behavioral pattern, patterns become machine-recognizable signals, and those signals in turn reinforce the emotional experience.

An Agentic Lovemark doesn’t start with technology, it starts with meaning. It then builds the structure that allows that meaning to survive, scale, and be recognized in a mediated world. This is the loop.

What matters isn’t the individual stages in isolation, but the way they compound. An Agentic Lovemark is a brand that can move through this loop again and again, each cycle deepening emotional relevance while increasing structural legibility.

Meaning: Where love begins

In a world where AI agents compress entire markets into a handful of suggestions, emotional meaning becomes denser. The agentic economy tasks meaning with double duty: ignite love in humans while providing the coherence that intelligent systems interpret as legibility and, over time, trust.

Humans feel. Machines read.

The brands that will survive are those whose emotional meaning is (a) articulated sharply enough to resonate with people and (b) structured clearly enough to be recognized by systems. The former begins with a pairing that has shaped the world’s strongest brands for decades: an emotional territory and the organizing idea that gives it form.

You see this pairing with leading brands across categories. Nike draws its strength from the emotional territory of empowerment. Its organizing idea, “If you have a body, you are an athlete,” reframes empowerment as personal agency. Apple’s territory is clarity and creative control. Its organizing idea of “Unleashing Creativity” occurs by removing friction and complexity. IKEA’s emotional territory is the dignity of everyday life. Its organizing idea, “Design for the many,” democratizes good living.

Sometimes the articulation of a territory is so strong and so true to human experience that it outlives categories, campaigns, and leadership cycles. I personally witnessed this firsthand during a project in 2000, when we discovered the train to be one of the few places where people regain their own time. The emotional territory became reading—not as pastime but as self-development, reflection, and calm. The organizing idea “Time for Reading” (“Tijd voor Lezen”) gave that insight a voice, a direction, and a cultural center of gravity. It reframed the journey as a moment of possibility rather than delay.

A quarter of a century later, the territory still shapes the cultural presence of that brand.

I’m not the least bit surprised. Emotional territories endure when they express a timeless human need, and organizing ideas endure by giving that need a recognizable rhythm—meaning that can be expressed, repeated, recognized, and now, made legible.

Pattern: Where emotion becomes legible

Emotional meaning, no matter how resonant, cannot garner market power without repetition. It can’t in the physical world, and it can’t in an agentic one either.

Intelligent systems don’t feel the emotional territories that humans respond to, nor do they intuit organizing ideas. They identify meaning through patterns: consistent behaviors, repeated signals, stable signatures. Without an organizing idea to shape and stabilize that meaning, emotional expression becomes fragmented (no patterns), and agents read fragmentation as unreliability.

Meaning isn’t just the beginning of love. It’s also the architectural beginning of trust in an agentic world.

While meaning defines the emotional truth, pattern is where that truth enters the observable world. This shift is subtle but decisive. A brand becomes visible not because a system understands its intentions, but because the system sees a stable rhythm in its behavior.

You recognize this in brands long before algorithms do. The clarity of Apple’s interfaces, the moral compass of Patagonia, the dignified simplicity of IKEA aren’t campaign artefacts. They’re behavioral signatures shaped by an organizing idea and repeated often enough to become unmistakable. Which is precisely what makes emotional meaning visible to machines. It’s not the emotion itself, but the consistency of its expression.

Patterns, in other words, are where emotion (i.e., love) becomes legible. And while it’s easy to see patterns as the end of emotions, it’s also incorrect. Patterns are emotions gaining structure. They provide the repetition, coherence, and behavioral traceability that systems rely on. Without pattern, emotional meaning remains invisible; and without meaning, patterns would simply be mechanical.

Recognition: Where systems understand what humans feel

In the offline world, patterns are rarely designed; they emerge. And they crystallize where the organizing idea meets lived experience. The pattern across “Time for Reading”, for example, didn’t begin in communications but in small moments throughout the journey. The quiet ritual of passengers opening a book, the soundscape of a carriage, the reflective posture people adopt during travel. These moments formed a behavioral rhythm that reinforced the emotional meaning people associated with the brand.

In an agentic world, a brand may express its organizing idea through countless small behaviors, but those behaviors must eventually cohere into something more: a recognizable structure. Such structure only emerges when a brand’s organizing idea governs real interactions—when tone, service, choice architecture, product logic, and micro-gestures align around the same emotional center.

This is where the loop tightens. What begins as emotional meaning becomes sustained behavioral coherence over time, with patterns taking on qualities that agents interpret as stability: high engagement, cultural stickiness, recurring participation—all signs that a brand’s emotional meaning has become structurally real and consistently recognizable.

Humans and machines arrive at recognition for entirely different reasons. Humans recognize a brand because it feels like itself, because its meaning appears reliably across contexts. Machines recognize a brand because it behaves like itself, because its signals form a pattern that stands apart from the background noise. Today’s intelligent systems can detect the outcome, the stable preferences, the return behavior, the resistance to switching, even if they cannot understand the feeling that caused it. And when human behavior toward a brand exhibits the same emotional logic across contexts, agents interpret this as preference stability.

Two forces make patterns powerful in the agentic age: First, repetition creates recognition. Second, distinctiveness creates memory.

This is where the organizing idea evolves from a source of meaning to a source of pattern stability. People see this in brands long before agents do. Apple’s devotion to clarity is visible not only in design but in defaults, gestures, interfaces, product architecture, and the culture of restraint that surrounds everything the company makes. Patagonia’s activism shows up in materials, tone, business decisions, legal actions, and the multifaceted insistence that business must repair the world it affects. IKEA’s design-for-the-many philosophy manifests everywhere, from flat-packing and price engineering to tone of voice and spatial logic.

These brands behave with such internal cohesion that their meaning becomes structurally obvious to us. This is where the Brand Constitution proposed by Marzano becomes essential. Not as bureaucracy, but as the intentional codification of that cohesion: the myth and purpose that ground it, the signatures and tones that express it, the quests that direct it, and the rendered behaviors that make its patterns visible.

The Constitution doesn’t replace emotion, but it does render emotion into form. Recognition, then, isn’t the end or even reduction of love. It’s love acquiring a sturdy structure that both humans and systems can follow, the moment when meaning becomes machine-evident without losing its humanity.

Reinforcement: Where love and machine trust amplify each other

Meaning becomes pattern. Pattern becomes recognition. Recognition, once achieved, sets a different dynamic in motion, one that neither Lovemarks nor classic brand theory fully anticipated, but which becomes decisive in an agentic economy: self-reinforcement.

When a brand’s emotional meaning is strong enough for humans to feel and structured enough for systems to read, the two forms of preference begin to amplify one another. Human experience and machine mediation no longer operate on parallel tracks; they form a flywheel. For humans, reinforcement emerges through emotion: familiarity, ritual, identification, the small satisfactions and repeated reassurances that make a brand feel like a personal fit. For systems, reinforcement emerges through underlying patterns: recurrence, stability, coherence, the signals that indicate a brand is trusted, chosen, and returned to.

Once a system surfaces a brand more often, people increasingly bump into it in moments that matter. That extra visibility creates more chances for emotions, which in turn, leave stronger traces in consumer behavior. Stronger traces make the brand easier to recognize by the systems, pushing it back up again.

Hence, the Agentic Lovemark Loop. Stronger signatures produce clearer machine recognition. Clearer recognition produces even greater visibility. We go from meaning to pattern, to recognition, to exposure and emotion (as reinforcement), and back again to meaning.

Although not yet agent-driven, you can retrospectively see this dynamic—to a certain extent—in the “Time for Reading” example. The initiative began as meaning, became lived behavior, and grew into a cultural pattern. For 25 years, the association between train travel and reading has been reinforced through countless micro-moments, sustained cultural partnerships, and the simple fact that meaning survived leadership cycles, campaigns, and societal shifts.

In a world shaped increasingly by intelligent agents, such long-term behavioral regularity will become a strength: The system sees what people have felt all along—a stable, distinctive rhythm that stands apart from alternatives. Such cultural density becomes a form of structural advantage.

Reinforcement is when brands stop having to push so hard to be seen; the same systems that once challenged their visibility start pulling them into the picture.

The brand no longer depends on campaigns to assert its meaning because its meaning is already encoded in behavior, culture, and system logic. This is the architecture of the Agentic Lovemark: not a break from the Lovemarks philosophy, but its evolution for a world in which emotional value must be both deeply human and structurally legible. A world in which the brands that endure are those whose meanings are strong enough to live in hearts and clear enough to live in systems.

The creative fear

In parallel to the strategic debate about agents and machine-mediated choice, a more visceral conversation is happening inside the creative world. It isn’t about funnels, metadata, or shortlists. It’s about soul.

For decades, creatives have understood that the magic of a brand often lives in what cannot be optimized: timing, tension, imperfection, risk—the slightly crooked line that somehow feels more human than a perfect one. That is why so many creatives instinctively resist AI. They don’t fear systems; they fear perfection. They fear the smoothing out of everything that gives work its emotional charge.

Dutch creative legend, Aad Kuijper, expressed this tension sharply when he argued that you cannot fake attention, you cannot fake soul, and that people have an almost physical allergy to anything that feels too flawless or engineered, whether it’s AI-written copy, a synthetic voiceover, or a plastic Christmas tree.

Kuijper’s critique highlights an undeniable truth: AI has no lived experience. It has never failed in a studio. It has never fought with a director. It has never made a choice that cost someone sleep. People instantly feel when creative work loses these traces of effort and emotion, yet this creative fear and the rise of agentic mediation are not one and the same. They describe two different realities.

The first reality is about who makes the work, humans or machines. This is a creative question: should AI ever be allowed to generate the emotional core of brand expression? I believe the work of making people care must remain human, for authenticity cannot be automated. AI can assist the process, but it cannot replace the practitioner. AI is much closer to a Formula 1 car than to a driver. It’s a machine of extraordinary capability that can enhance strategy, broaden exploration, and accelerate iteration, but it still takes a professional behind the wheel to win the race.

The creative judgment, the ability to sense what moves people, remains human work. AI can increase the power of that craft, but it cannot become the craft itself.

The second reality is about who mediates choice, humans or agents, which is a question of structure rather than creativity. Intelligent agents will increasingly filter, rank, and recommend brands on behalf of people. For that part of the system to work, brands must be clear, coherent, and legible. Not perfect, but interpretable.

Seen this way, the creative critique isn’t an argument against machine trust. It’s an argument against confusing legibility with authenticity. AI should not create love, but it should help reveal the love that actually exists. After all, our purpose here isn’t for machines to manufacture emotion, but for real emotion to become legible through the behavioral patterns that love leaves behind and the reliability that machine trust provides.

This is how we can ensure that human-driven meaning doesn’t disappear in a machine-sculpted world, thereby strengthening the case for Agentic Lovemarks. The creative fear reminds us that emotion must remain human, even as its consequences extend into systems. It protects the soul of the work, while allowing the structure beneath it to evolve. And it ensures that love remains the center of the model, not an artefact of nostalgia.

Lovemarks in the agentic age

With these foundations in place, the evolution becomes clear. Lovemarks don’t disappear in the agentic age, they evolve. They evolve because trust evolves, because mediation evolves, and because the relationship between humans and brands is now shared with intelligent systems. Their purpose, however, remains the same: to build meaning, create emotion, and earn preference. What changes is the structure beneath that meaning.

Respect, once formed entirely in the human mind, now flows into machine trust. Not because rational confidence matters less, but because it must now be expressed in structured, verifiable, and machine-readable form. Love remains fully human and becomes even more important. Meanwhile, machines cannot feel emotion, but they can amplify its effects and so, end up stabilizing the very preferences that emotion creates.

The rise of intelligent agents doesn’t diminish the role of emotion in brand building. It clarifies it.

In this landscape, the Lovemark organizing idea becomes the organizing force of the brand, joining emotional soul with systemic logic inside the Brand Constitution. It connects the narrative people feel with the patterns agents can interpret. It ensures that emotional meaning doesn’t dissolve into optimization and that machine clarity never empties the brand of humanity.

These shifts culminate in a new kind of brand ambition: the Agentic Lovemark. Not a new category, but the next chapter of what Lovemarks have always pointed toward. Brands that matter deeply to people, remain coherent to systems, and stay held together by a single guiding idea. Brands with a soul and a system, loved by humans and recommended by machines.

Emotion makes a brand meaningful, while structure makes it visible. Together, they make it chosen. This creates the exact phenomenon Marzano describes: lovability remains deeply human while becoming partially machine-interpretable. Agents won’t be responding to the love a brand self-proclaims in its websites or campaigns, but to the love that actually exists. The love that’s built into the brand and encoded within its visible behaviors, patterns, signatures, and decision logic.

The opportunity is historic. And the responsibility is real. To build brands for human hearts and machine minds, where emotion is matched by clarity, meaning by structure, love by machine trust, and soul by system.

This is the challenge that will define the next generation of marketing—and Lovemarks.

Cover Image Source: Master 1305