Take a peek under the hood of any brand league table and you may notice that many of the brands listed have stretched far beyond their initial application. Samsung started life as a grocery business. Nintendo used to make playing cards. Netflix was a mail-based rental business.

And it isn’t just technology brands that have leaped nimbly from one category to another. Toyota used to make looms for weaving. Lego started life as a carpentry workshop. Wrigley’s was a soap business years before it became a gum business. Brands have a remarkable ability to help businesses transcend categorisation. But misadventures are as easy to find as success stories: the Amazon phone, Colgate lasagne, the Evian bra.

It would be cute of me to argue that great strategy is what sets the success stories apart from the cautionary tales: in many of the examples above, luck, necessity and tenacity almost certainly played a bigger role. But businesses tend to be luckier and more determined when they have the confidence of a well-conceived strategy in their back pocket. And I’m a brand strategist. So, I’m bound to focus on the question of when, why and how to stretch a brand.

The when

When to stretch is the easiest of the three to answer.

To paraphrase ex-GE CEO, Jack Welch: the best time to think about stretching your brand into new areas is ‘before you have to’. It’s bonkers to wait until your core business is in decline to explore new frontiers. Growth is an imperative for pretty much every organisation I’ve ever worked with and it’s common to include some analysis of stretch opportunities in the strategic planning cycle: usually within an innovation roadmap. Businesses that take growth seriously (as most do) are in a constant state of brand stretch. Sometimes this involves giant leaps into new spaces but more often it’s about exploring ideas in adjacent areas. Software businesses launch their own hardware. Restaurant brands unveil supermarket ranges. Apparel brands create products you can use to dress your home. Stretch happens in small steps as well as giant leaps.

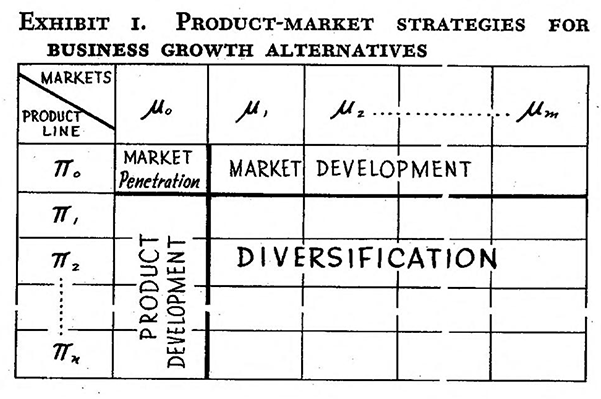

This idea is most famously captured in Igor Ansoff’s eponymous matrix, which he introduced in a 1957 article called ‘Strategies for Diversification’. Ansoff identified four basic alternatives for growing a business: increasing penetration; market development; product development; and diversification. Ansoff was particularly interested in the ‘unique problems’ posed by diversification, since this involves ‘a break with past patterns and traditions of a company and an entry onto new and uncharted paths.’

The idea of a ‘mission’ is critical to Ansoff’s matrix: he defined this as a description of the ‘job’ a product is intended to perform (an idea that has since evolved into the concept of a ‘Job to Be Done’). Ansoff’s matrix maps different product lines (represented by px) against a corresponding set of product missions (represented by mx):

In terms of Ansoff’s matrix, a market penetration strategy is an effort to grow an existing product’s sales (p0) without departing from its original mission (m0). A market development strategy extends an existing product line to new missions (for example, when Lucozade began to market itself in the 1950s as an everyday energy drink, rather than a way to recover from illness). A product development strategy involves developing products with new and relevant characteristics that better deliver on an established mission (for example, when Qantas introduced Business Class in 1979 to better meet the needs of corporate travellers). And diversification is the most radical of the growth strategies: a simultaneous departure from existing product lines and missions.

In terms of Ansoff’s matrix, a market penetration strategy is an effort to grow an existing product’s sales (p0) without departing from its original mission (m0). A market development strategy extends an existing product line to new missions (for example, when Lucozade began to market itself in the 1950s as an everyday energy drink, rather than a way to recover from illness). A product development strategy involves developing products with new and relevant characteristics that better deliver on an established mission (for example, when Qantas introduced Business Class in 1979 to better meet the needs of corporate travellers). And diversification is the most radical of the growth strategies: a simultaneous departure from existing product lines and missions.

The term ‘brand stretch’ can refer to any of the non-penetration growth strategies. Many businesses simultaneously pursue a combination of all of the above: growing penetration of ‘core’ products, balanced with existing product development (EPD) and new product development (NPD). Ansoff would have approved: much of his article is devoted to the thorny issue of uncertainty. Although we tend to think of our own time as uniquely uncertain, successful businesses in 1957 had to pivot their way through two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Korean War, the Cold War, the proliferation of general-purpose computers, the de-industrialisation of Western society, the adoption of television as a popular medium for communication and the rise of what we now recognise as consumerism.

Diversification is the best response to uncertainty: companies that focus exclusively on penetration of existing product lines in existing missions pile all their eggs into a basket that nobody can be sure will still exist in twenty years’ time. And according to Ansoff, diversification strategy is fundamentally about answering two questions:

- How well will a particular move (if it is successful) meet the company’s broader objectives?

- What are the company’s chances of succeeding?

Or, in other words:

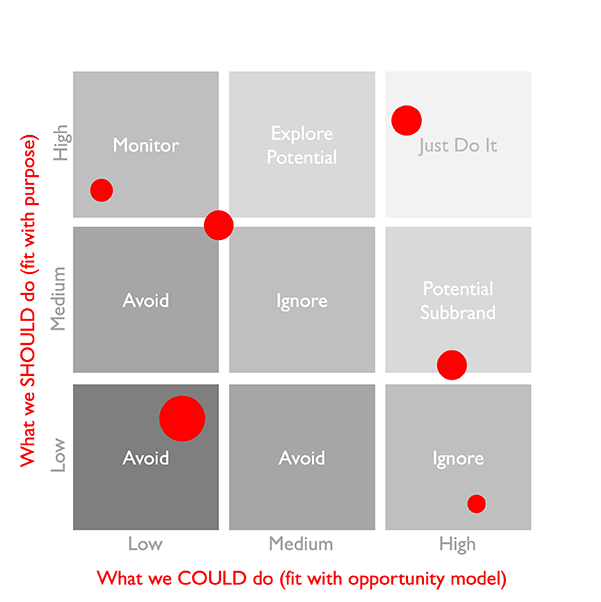

- What SHOULD we do?

- What COULD we be great at doing?

Ansoff’s article wasn’t particularly concerned with brands or branding, but these are also great questions to answer from a brand perspective. And they relate to a central preoccupation of brand strategy–why?

Because if you can articulate why your brand should stretch, then you’re halfway to working out when and where it should and could stretch.

The why

For my money, Jim Collins is the closest thing the brand world has to a present-day Igor Ansoff. I don’t know him, I’ve never met him, but I find his thinking extremely seductive and, on the subject of brand stretch, extremely helpful. His books are all worth reading at least once, but you’ll also get a helpful taster of his ideas for free on his website.

Two of my favourite Jim Collins articles relate to brand stretch and the two questions above.

In ‘It’s not what you make, it’s what you stand for’, he picks up on one of Ansoff’s themes: that concentrating too much on the products and services you already sell is a trap. An organisation that defines itself as a television manufacturer will always be limited by this belief. On the other hand, an organisation that makes televisions with a higher purpose in mind will be able to find novel ways to achieve this purpose, even if the market for televisions declines. Although many advocates of brand purpose are drawn to Simon Sinek’s impassioned call-to-arms, I prefer Jim Collins’ harder-nosed, more commercial rationale: a brand purpose is more than a way to inspire colleagues; it’s a way to help an organisation choose which diversification opportunities to consider. And for the record, I don’t particularly care whether you call this a purpose, a vision, a mission, a positioning, a promise, or a proposition, as long as it establishes a clear direction for the organisation.

Brand purposes are easy to ridicule, particularly when they err into the territory of corporate self-congratulation. I won’t purpose-shame the businesses that indulge in this, but there are plenty of them. At the other end of the scale are the organisations who take their missions seriously as brand stretch tools. One of my favourite examples is Google: its mission is ‘to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.’ This has given the company licence to stretch far beyond its ‘core’ business of Internet search into maps, academic research, images, songs, financial indices and video. One of the acid tests of a strong brand purpose is that it can be used to identify areas that an organisation should stretch into, and distinguish these from those where it shouldn’t, even though these might be commercially attractive.

This is a crucial area of overlap between Igor Ansoff and Jim Collins: you filter opportunities based on your broader strategy (or purpose, or mission, etc.) before you contemplate commercial attractiveness. This prevents the type of financial opportunism that often undermines long-term brand-building: ‘activity x doesn’t really fit with our brand but it’s achievable and we can make money doing it.’ And this is exactly the kind of thought process that results in Colgate lasagne and Evian lingerie.

In a related article ‘The Hedgehog Concept’, Jim Collins refers to the ‘curse of competence’: there will inevitably be countless opportunities for growth and profit that an organisation could pivot towards, but pursuing these results in brands that are ‘scattered, diffused and inconsistent’.

Instead, he urges brand owners and managers to behave more like Isiah Berlin’s fabled hedgehog, which outwits a fox that knows many things, simply by knowing one big thing.

However many categories a brand stretches across, it should remain similarly single-minded.

This is about more than just clarity of purpose: it’s also about understanding what you’re capable of delivering really well (and really profitably). Your purpose (or mission, or positioning, or proposition) statement should clarify what you should do. This can be used to qualify potential stretch areas. But Ansoff’s second step is just as necessary: further qualification based on what you could be great at doing.

So, how do you work out what you could be great at? One way is using a specially adapted Opportunity Model, which brings together internal and external factors into a single framework:

Stretch opportunities can be assessed either qualitatively or quantitatively using this (or a similar) framework:

Stretch opportunities can be assessed either qualitatively or quantitatively using this (or a similar) framework:

Building on the commercial plan:

- How large is the stretch opportunity in financial terms?

- How confident are we that we could generate incremental sales and translate these into accretive earnings?

Reflecting the company:

- How well matched are our culture and capabilities with each stretch opportunity?

(or does it provide an opportunity to adopt valuable new ways of working) - Does the stretch opportunity enhance, complement, distract or detract from our existing business?

Connecting with customers:

- How satisfied are people with what’s currently available?

- How strong a relationship do we already have with these customers?

- How well does our brand fit with their ideal offer?

Distancing from the competition:

- What can we bring to the stretch category that existing brands don’t?

- Which category rules are we be able to / prepared to break?

Being in tune with the context:

- What are the social, technological, environmental, legal and political forces shaping the future of our brand, and how does each stretch opportunity help us to anticipate and respond to these?

The ideal brand stretch opportunity will perform well against these criteria, as well as fitting with your brand purpose:

The majority of brand stretch opportunities are unlikely to be such obvious no-brainers: it’s more likely that some opportunities will fit well with your purpose, but only be of moderate fit with the opportunity model (in which case they are worthy of further exploration), or that others will fit well with your opportunity model but not so well with your purpose (in which case a subbrand could be a more appropriate way to stretch without diluting the brand). The matrix above can be used to map your entire portfolio: not just diversification opportunities but product line extensions, market developments and penetration growth opportunities. It can be used to map organic growth opportunities as well as potential acquisition targets. Most diversification opportunities are likely to fall short and this is where discipline becomes important: it’s better to invest in growing your existing business through penetration and EPD than stretching into areas that have only a weak chance of building your brand or your business.

The how

So far, I’ve concentrated on strategy, but that’s only the beginning of the story. Brands that are truly great at stretching tend to have a very specific style: they apply a common set of principles to any category they compete in. For a wonderful example of this, consider the 40-or-so years Dieter Rams spent at Braun: a period in which the brand launched over 500 products across categories as diverse as whisks, pocket radios, alarm clocks, calculators and electric shavers. As head of the design department, Rams developed a very specific philosophy of form and function, with a signature style that was systematically applied to every aspect of the brand experience.

Over the 1970s, Dieter Rams crystallised this philosophy in ten principles for good design:

- Good design is innovative

- Good design makes a product useful

- Good design is aesthetic

- Good design makes a product understandable

- Good design is unobtrusive

- Good design is honest

- Good design is long-lasting

- Good design is thorough down to the last detail

- Good design is environmentally-friendly

- Good design is as little design as possible

These principles were all developed in the context of a wider guiding belief (or brand purpose): that good design can make lives better, provided it is simple, useful, and built to last. Nearly half a century later, these same principles are evident in every product, space and experience that carries the Braun name. This single-mindedness of approach is what allows brands to stretch across seemingly unrelated categories: no matter where they show up, they are always recognisable because they bring the same ethos to bear. Virgin has been able to stretch from music into airlines, gyms, banking and media because it innovates with a clear idea in mind: ‘changing business for good.’ As a consequence, we know what to expect when the Virgin brand stretches into a new category – no matter what the category.

In practical terms, a purpose or mission statement often isn’t enough: it establishes a sense of an organisation’s ‘true north’, but important nuances are difficult to capture in a single statement. This is why organisations (sometimes) establish a supporting set of principles or ‘guardrails’ to guide decision-making around brand stretch and innovation. These guardrails add specificity to the brand purpose or mission statement and provide a more formal framework for guiding how the organisation should stretch (once it has decided which areas to stretch into). Not every brand has a formal set of principles, but it’s something I encourage. Brands that are great at stretching aren’t just disciplined in selecting when and where to stretch: they are also disciplined in how they stretch. The result is a signature style that becomes more unmistakeable with every leap into a new category. Over time, people even begin to anticipate how brands might stretch into new areas: from Apple furniture and Bang & Olufsen smartwatches to Braun cars.

Great brands stretch in their own unique style

Unfortunately, style is underrated as a business tool, with the sad consequence that brand stretch more often mystifies than makes sense. When a brand is clear about why to stretch, where to stretch and how to stretch, the result is often so obvious to potential customers that relatively little resource is required to sell them on the idea. As the examples above demonstrate, if a brand is single-minded enough in its approach, people are often willing to make great leaps of imagination for themselves. It’s amazing how far you can go with a single-minded purpose and a clear set of guiding principles.

Cover image source: vicenola