Not everything is a brand. Everyone is not a brand. Everything is not a brand. Sorry, but that’s the way it is.

People and things may be known, even well-known, but that does not make them brands. Calling yourself a “brand” doesn’t make you one. That’s problematic and simplistic. Real branding is never simplistic. Why would anyone think it was?

I blame Tom Peters.

Mr. Peters knows a lot about “excellence”, but did branding a disservice. In his 1997 Fast Company article, “The Brand Called You,” he advocated anyone could be a brand. In doing so, he opened a Pandora’s Box of branding horrors, á la personal branding, an outlook that transformed into routine practice.

Three things are necessary for a product or service to be adjudged a brand. They need to be:

- Imbued with meaning;

- Differentiated from the competition, and;

- Emotionally engaging to consumers.

Sure, you have to be “out there” and known, but that’s marketing. Consumers, the marketplace, and category and customer values are never static. Everything changes, true before the pandemic, which obfuscated an already-muddled brandscape. To provide clarification, we conducted a study to identify what it means to be a “brand” today.

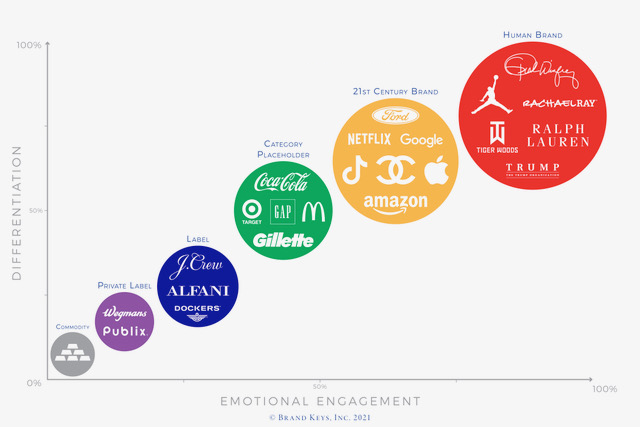

The survey, conducted in May 2021, in the U.S. and U.K., included 1,994 products and services in 128 categories, B2C, B2B, and D2C, digital, analog, traditional, online, bricks-and-mortar, clicks-and-mortar, and app-based. The methodology uncovered a series of loci along which products and services could, via consumer assessments, be “placed,” identifying the degree to which they were actual brands.

The continuum includes brief definitions of where “products and services” could fall, and some examples. By more accurately situating products and services, marketers can sidestep semantic arguments and strategically differentiate, engage, and market on the basis of a product’s or service’s actual status.

The degree of “brandness” (consumer emotional engagement potency) escalates as one migrates from left to right on the chart. As brand differentiation increases, the sector rises. It’s true one can be profitable as a “label”, and fortunes can be amassed in “commodities”, but that still doesn’t qualify them as “brands”.

Commodity: Basic products and services, undifferentiated in the minds of consumers; interchangeable and usually sold on price.

Label: The name of a retail store or manufacturer identifying goods; often providing rational information about the product.

Category Placeholder: Products or services with universally strong awareness. Known but not known for anything other than occupying a space in a category. Has values so basic, differentiation via emotional engagement is difficult to attain. Products or services that at one time were brands, but are no longer brands as 21st-century consumers define them.

21st Century Brand: A name, term, and/or symbol identifying goods and services of one seller versus another. Strongly imbued with values and articulated meaning as to be easily differentiated from the competition, with an identity by itself engendering high consumer emotional engagement.

Human Brand: A nomenclature (created by Brand Keys, 1991) to describe living human beings that represent 100% of the values of the products or services to which their names are attached. The highest level of imbued meaning and differentiation as living embodiments of particular values (“owned” by the human being), which can be seamlessly transferred to products and services.

What about those famous people online and on TV? Aren’t they brands? No, they’re celebrities. Being a celebrity does not QED a “brand” make. Models are not brands, but a subset of celebrities, hired to impart aura and image, but are not, in and of themselves, the brand.

Eminent or legendary businessmen are not brands. Elon Musk and Richard Branson are not brands. They’re entrepreneurs who created brands. There are business people who founded brands, like Henry Ford or King Camp Gillette. How brands like those have been managed determines whether they are now “Category Placeholders” or “21st Century Brands”.

“Everything-is-a-brand” plays well in classrooms and in Tweets. But identifying brand bona fides is more critical than ever. And, answering the following questions is crucial:

- What’s on offer beyond primacy-of-product?

- How are you differentiated?

- Do you represent meaningful values that emotionally engage consumers?

- Do you meet or exceed expectations consumers hold for the ‘category ideal’?

How you answer and where you fall on the continuum provides the ultimate answer to the question, “Are you really a brand?”

Cover image source: Merlin lightpainting