We’re told that keeping it simple is core to building an accessible brand, but great brands are built from dramatised details rather than abstract generics.

A core tenet of brand-building is to keep your messaging focused and easy to understand. People usually give communications and ads little attention, so whatever you say needs to be simple, understandable and memorable. Not only that, but it must also be attributable to your brand, building memory structures over time.

For some categories, that’s an easy task. Have you got the same thing as everyone else with an extra twist? That’s great. Tell everyone about the difference, and let them fill in the gaps! Familiar categories have memory structures so that brands can double down on the differentiating factor.

However, for complex and innovative products, the type often found in university spin-outs or resulting from research challenges, the need to simplify can often result in dumbing down the message to an easily duplicated or ignored level.

These organisations might be trying to catch the attention of investors who don’t have time to get into the detail of every new product they come across. Or they’ve saturated the early adopters and need to reach broader audiences. Whatever their reasons, they hit the stage where their complexities hold them back in communications. At this point, the precise details of the innovation are thought to be too complex to grab attention, and they opt to cut it down.

Here’s the trap. Ask any writer, there is a big difference between simplifying and removing content that doesn’t add to the story.

So many innovative brands chose the former, laddering up to trite anodyne statements which, though perhaps attributable to their products, don’t distinguish them from their competitors.

Take Smart Photonics in the Netherlands, manufacturers of complex microchips needed for things like quantum computers (I think!) Do they prioritise what makes them great and differentiates themselves from competitors? You tell me: “Bringing your innovation to life. The leading foundry for integrated photonics, creating innovative products that improve people’s lives.”

Or Anjarium Biosciences, according to Sifted, is “developing DNA-based gene therapies to treat genetic diseases that are more predictable and inclusionary than current methods.” That’s cool. Inclusivity is a key issue in bioscience, so they will use it… “Pioneering the next generation of non-viral gene therapy.” Doh!

Smart Photonics and Anjarium Biosciences are doing smart things very well, and I don’t mean to pick on them. They just had the misfortune of being the first two deeptech brands I encountered in a search. The problems are endemic to the category.

And it’s not just a business problem. In the paper, Marketing Ideas: How to Write Research Articles that Readers Understand and Cite, researchers found that academic scholars “write unclearly in part because they forget that they know more about their research than readers”. They lay out the ‘curse of knowledge’, where in-depth familiarity with a subject makes communicators more prone to be more abstract, technical, and write passively. Given that many innovative products come from university spin-outs, it’s no surprise the problem extends into business.

These innovators must remember that great brands are built from interesting stories. Instead of simplifying the whole product, brands built around complex products and services should find interesting details and dramatise them. But it can be challenging to see what makes your business special when you’re close to the details, so here are three prompts to help you stay simple and interesting.

Keep an eye on the category

Dumbing down affects everyone, and you can often spot common simplifications to avoid across your competitor set. A straightforward trick is to copy and paste your competitor’s website copy into a blank document, remove the brand names and ask someone slightly removed from the category to go through the paper and highlight the repeated phrases. If you’re short on friends to pressure into this, BingAI does a good job of spotting the similarities too.

Find the differences and motivations

Secondly, become a product and brand investigator, analysing and detailing your motivations, product and competitors. Break your findings into clusters relevant to your category, and don’t let up until you’ve found a unique difference, no matter how small. It doesn’t necessarily have to be the critical part of your technology; it just has to be the basis of an interesting story. What a friend calls the ‘chocolate in the chili’ (because adding chocolate to a chili con carne improves the dish’s flavour).

Dramatise the difference against audience needs

Once you’ve found the difference, bring it to life distinctively and compellingly. It doesn’t have to be a novel – illustrate the difference and how your audience’s world will differ as a result.

We’re often asked to start with why, but I advocate we start by answering so what?

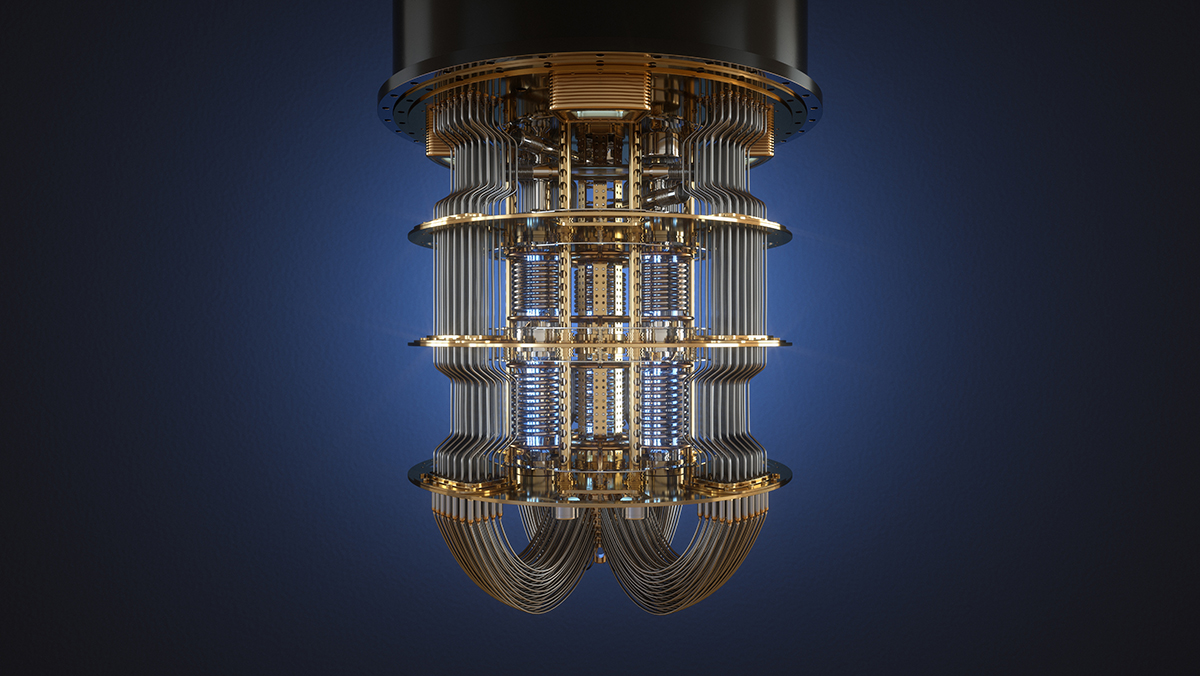

Let me give you a quick example of a business doing it well. PsiQuantum is in the business of quantum computers, where despite each company having its way of building them, no one has yet managed to produce them at scale. Competitors generally focus on their particular method of making quantum bits. But here’s how PsiQuantum introduces itself: “PsiQuantum – Building the first useful quantum computer.” Simple but effective, focusing on the audience’s need and boldly inviting the reader to ask why their product is useful when others aren’t. What they do and why they do it in six words.

Putting these simple steps into practice should help us reach a place where complex products get the attention they deserve, not by dumbing it down but by dramatising the details.

Cover image source: Negro Elkha