Naomi Klein published No Logo nearly 25 years ago, around the same time I started working in branding. Her book was hugely influential: a call to arms for branding sceptics and discontents of globalisation. It identified branding as a form of corporate misdirection: A successful lie that companies like Disney, McDonald’s and Nike relied upon to divert attention from the dirty truth that First World consumption typically comes at the expense of Third World workers (I’m paraphrasing here).

No Logo described the system that branding facilitates as a balloon economy: “It inflates with astonishing rapidity but it is full of hot air.”

Branding (and, by association, marketing) consequently tended to attract a significant amount of suspicion. It was “fluff” in a number of senses:

- Branding was seen as a way to make organisations and their products appear fuller and more wholesome than reality (a way to ‘fluff up’ a product and its retail price, in the same way that we might fluff up a pillow).

- Branding was seen as a way to trivialise the underlying conditions in which these products were made (and who they were made by) by directing attention to more immediate and superficial aspects of the consumer experience (a way to add a layer of “Hollywood fluff” to a sweatshopped product).

- As a result, branding professionals were “fluffy” in the sense of being soft-headed: divorced from the commercial realities of supply chains, profit-and-loss accounts, shop floors and production lines (and far too concerned with colour palettes, photo shoots and long, boozy lunches).

There are at least three forms of scepticism lurking in these accusations:

- That branding is dishonest. That it involves telling lies about how products and profits are made.

- That branding is delusional. That it involves a detachment from reality.

- That branding is destined to fail because dishonesty and delusion are eventually detected and punished.

Growing up in the profession, I used to spend a lot of time making the case for branding: why it matters, why it’s a good thing (not an evil thing), and why it’s a sustainable source of success. Nowadays, I get a much easier ride. When I tell people I’m a brand strategist, they generally respond with polite interest rather than suspicion or hostility. But I think a little scepticism is healthy. And I think it’s also good to be able to answer the simple question: Why brand?

First of all, you don’t have a choice

Even the smallest organisations need to make decisions about how they want to be understood.

- What do we call ourselves?

- How do we describe ourselves in a way that people will find compelling?

- How do we name and present our products and services?

- What should our website look like?

- What sales materials should we use?

- What internal guiding principles should we follow?

- What tone should we adopt in our written and spoken communication?

- Should this tone vary depending on the medium through which we’re communicating?

No matter how little or large your organisation is, every interaction needs to be designed, so the only real decision is whether you’re going to do this intentionally or not. Will your answer to each of these questions be an ad hoc, off-the-cuff reaction? Or will it be part of a coherent, considered plan?

Branding isn’t about being delusional. It’s about embracing a reality every company faces: If you care about how people experience your organisation (this includes colleagues as well as customers), then the interactions you design should be the result of a careful, deliberate process. Quality of experience is a central aim of branding.

Second, companies with strong brands tend to experience sustained success

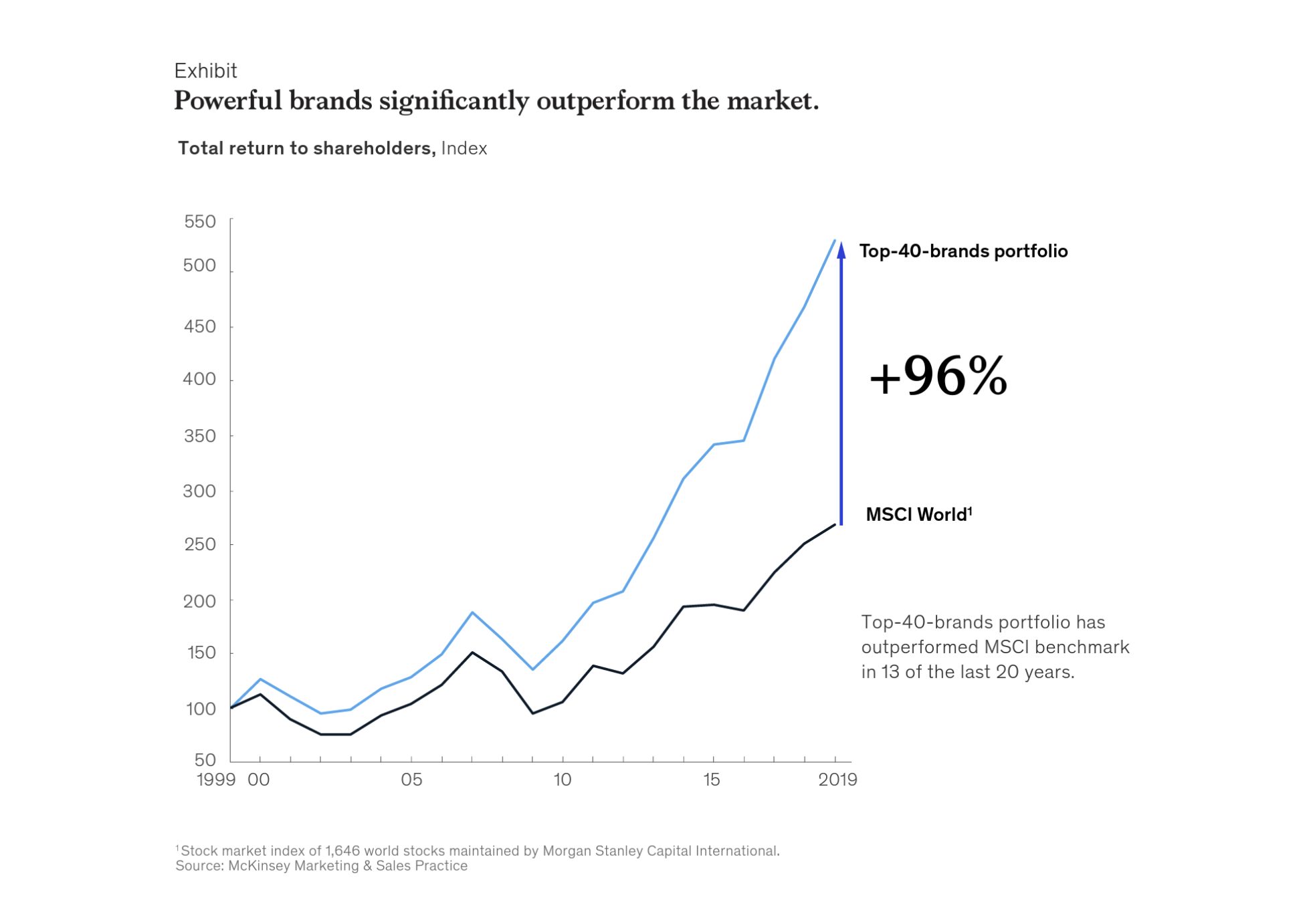

Strong brands consistently outperform benchmarks. You don’t need to take my word for this, pretty much any organisation that’s ever valued a brand portfolio reaches the same conclusion. Here’s an example from a 2020 McKinsey report:

In the same year, Kantar’s BrandZ study of the 100 most valuable global brands reached US$5 trillion, equivalent to the annual GDP of Japan (and an increase of 245% since 2006, well ahead of the S&P 500 and the MCSI World Index). Equivalent studies by Interbrand and Brand Finance reveal similar findings. The evidence all points in the same direction: It’s possible to build a successful organisation without a strong brand, but a business is far more likely to achieve sustained success if it benefits from having a strong brand (or a portfolio of strong brands).

Across these studies, brand value accounts for around 30% of total company value. For many organisations, brand is the single biggest asset in terms of value contribution. Their ability to manage their business successfully is intimately related to their ability to manage their brand successfully.

Third, brands reduce risk by facilitating long-term relationship-building

The value of any asset (including a brand) is a function of two things: (1) the incremental profits it will generate in future, (2) adjusted to reflect how certain (or uncertain) you are that these profits will materialise.

Although much of the literature on the benefits of branding focuses on their ability to stimulate additional demand for a company’s products and services, the second part of the equation is equally (if not more) important: Brands make businesses more stable by building trusting, lasting relationships between people and organisations.

- They encourage loyal customer relationships, advocacy and repeat purchase.

- They inspire like-minded organisations and individuals to collaborate on projects and share resources.

- They stimulate investors to provide cheaper and more plentiful access to capital.

- They draw media attention to new product and service launches.

- They help to attract and retain talented workers.

- They provide a licence to operate within a society or community from government, regulators, NGOs, cultural institutions and the wider public.

Value creation isn’t a simple matter of making a product or service and then finding creative ways to fool as many people as possible to buy it for as long as possible. It’s a collaborative process that requires relationship-building with many different groups of people.

Reciprocity is a more certain route to success than dishonesty.

Fourth, brands create growth by acting as a lightning rod for creativity

Although the new kids on the block tend to attract a lot of attention (Tesla, Apple, Meta, etc.), the world’s most valuable brand lists contain some extremely old brands: Louis Vuitton was established in 1854, Coca-Cola in 1886 and Hennessy in 1765. These brands were established by a recovered morphine addict, an itinerant farmer’s son, and a retired military officer, respectively. The brands they founded project their values and ideals indefinitely across time and space.

All of the world’s most valuable brands have a hidden, human origin story: a messy process in which oddballs, wanderers and retired soldiers are able to identify opportunities, develop ideas and persuade other people to invest their time and money in bringing those ideas to fruition.

As economist Deirdre Nansen McCloskey elegantly observes, “Ideas are the dark matter of history.”

And brands make this dark matter visible. They give form to the ideas and ideals that organisations need to thrive. To curiosity, empathy, originality, perseverance, integrity. Because these values can’t be directly measured or quantified, they are easy to overlook or dismiss as frivolous. But they aren’t. Reputations, cultures and – yes – brands are built on them. Once you give these intangibles a name, logo, and system of expression, you make them real. And once they become real, they can be legally protected, invested in, and bought and sold. They can function as central organising principles, helping organisations find ways to grow without losing their soul.

Fifth, brands make companies (and their products and services) easy to understand

Very few organisations sell a single product to a single audience. More commonly, organisations organise around a central idea and then develop portfolios of products and services that bring the idea to life for different audiences and applications.

For example, Google’s mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” It fulfils this mission through products and services like Internet search, web browsers, maps, phones, tablets, and academic resources. And to help us navigate our way around these products and services, it has created a system of expression: visual and verbal signposts that signal their various roles and relationships.

Google has also used this system of expression to convey an irreverent personality. There’s a parent company called ‘Alphabet’ that employs ‘characters’; a growth fund called ‘Capital G’; a set of whimsical ‘doodles’. Everything has been carefully conceived and created not just to please the user, but to make it easier for the business to cross-sell, upsell, point people towards important offerings, or direct attention away from speculative activities that might be sold or spun-off in future.

Although we frequently talk about them as simple, single things, most brands are systems rather than singular entities. They help make an organisation more efficient by providing a clear set of principles for how (and how not) to grow. And they help to make an organisation more effective by establishing intuitive ways for people to understand and navigate its products and services. The easier people find it to understand what you do and why, the more likely they are to appreciate your brand’s worth.

To paraphrase Michael Wolff, the whole of a company should be embodied in every single detail.

Done properly, branding is not delusional, dishonest or destined to fail. It’s a way to make organisations understood, liked, and even loved by the people they rely on for their existence.

Cover image source: michaklootwijk