According to Nassim Taleb’s ‘Lindy Effect’, every year an idea passes without extinction doubles its additional life expectancy. So, if a book has been in print for forty years, it can expect to be in print for another forty. And if it survives a further ten years, then it will be expected to be in print for another fifty years after that. Before I found out about the Lindy Effect, I assumed that ideas – particularly ideas in the field of marketing – had a finite and limited shelf life. But now I’m not so sure.

It’s been over a decade since Byron Sharp and his colleagues at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute published How Brands Grow and the popularity of his laws of growth seems as astronomical as ever. In the past two months alone, I have been provided with the marketing handbooks of four clients (all global brand owners, all likely to be in your fridge, or store cupboard, or drinks cabinet). The handbooks have strikingly similar titles (“The [insert brand here] scientific marketing approach”) and all four explicitly reference Bryon Sharp’s book and its laws.

Curiously, they also all include brand purpose, with the aim of establishing an approach to brand building that is simultaneously scientific and socially aware.

One reason I find this curious is that Byron Sharp has been extremely vocal in his derision of brand purpose. In a 2017 blog on why marketers aren’t respected, he echoed Mark Ritson’s description of brand purpose as ‘moronic’ and questioned the ethicality of spending shareholders’ money on ‘your favorite cause’. His apparent belief is that marketers who pursue a purpose, as well as profit, are in some way ashamed of capitalism, when they should be its most vocal supporters:

“They should be standing up proudly for the astonishing amount of choice that the modern market economy (yes, that’s capitalism) delivers. If we, of all people, don’t, who will?”

More recently, Byron Sharp told Campaign Magazine that “as marketers, particularly in this area of brand purpose, we are getting very arrogant”, citing the example of marketers who felt moved to acknowledge the Covid crisis in their advertising as a particularly hubristic waste of money. So, it seems odd to me that, despite their evident reverence for Byron Sharp and his views on branding, marketers persist in trying to combine his evidence-based laws with the more touchy-feely (or even ‘moronic’) concept of brand purpose.

What’s Byron Sharp’s take on all of this?

“Perhaps too many marketers learned their economic history in art school?”

Well… I work in marketing, and I studied economics. So, perhaps it might be helpful to provide a perspective based on economic history.

One of my favorite economists of all time is Harold Hotelling. He was a prolific American statistician and economist affiliated with Stanford University, Columbia University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was a mathematical economist, which Byron Sharp and his colleagues would presumably approve of. He lived between 1895 and 1973, and is the creator of Hotelling’s theory, Hotelling’s T-square distribution, Hotelling’s lemma, and Hotelling’s law. And it’s Hotelling’s law that demonstrates the difficulty of trying to combine Byron Sharp’s laws of growth with the concept of brand purpose. Bear with me here…

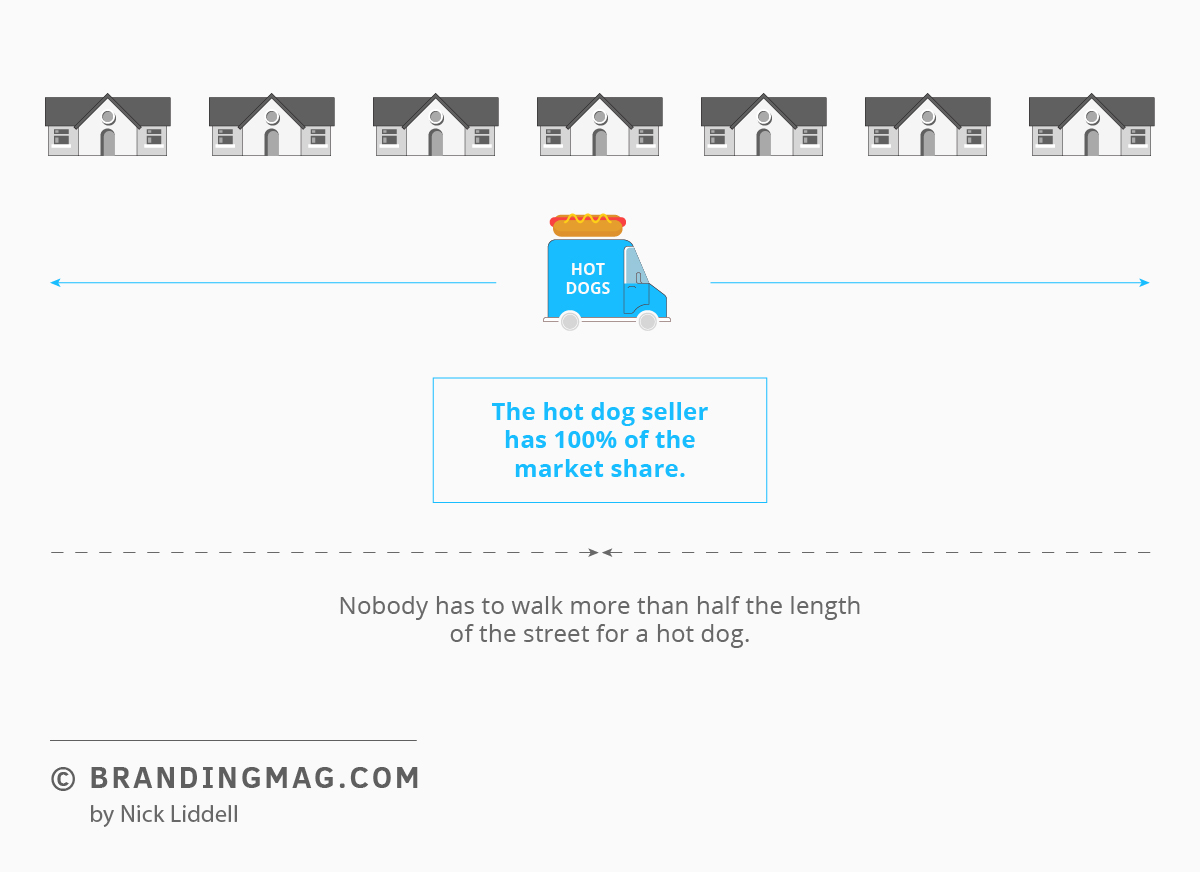

Hotelling’s law appeared in a 1929 paper on “stability of equilibrium” (“Stability in Competition”, Economic Journal), which was motivated by Harold Hotelling’s concern that political parties tend to be too much alike and cider too homogenous. He wanted to model whether capitalism results in ‘excessive sameness’, as opposed to, say, the ‘astonishing choice’ that Byron Sharp claims. To demonstrate his law, imagine a street that runs in a straight line from East to West, with houses and residents equally distributed along the entire street. Now, let’s say you want to set up a hot dog stand on that street. The logical place to position your stand is right in the middle: Nobody has to walk more than half the length of the street to get a hot dog, so you create the widest possible market for your fledgling business. So far, your commercial interests and the social good are beautifully aligned.

But this isn’t capitalism; it’s a monopoly.

So, what would happen if we introduced two competing hot dog stands to the street? And what, specifically, would happen if the entrepreneurs who owned each stand were fans of Byron Sharp?

Byron Sharp’s recipe for growth is fairly basic:

- Build ‘physical availability’ (make your brand as easy to buy as possible);

- Build ‘mental availability’ (make your brand as distinctive and memorable as possible).

Building physical availability

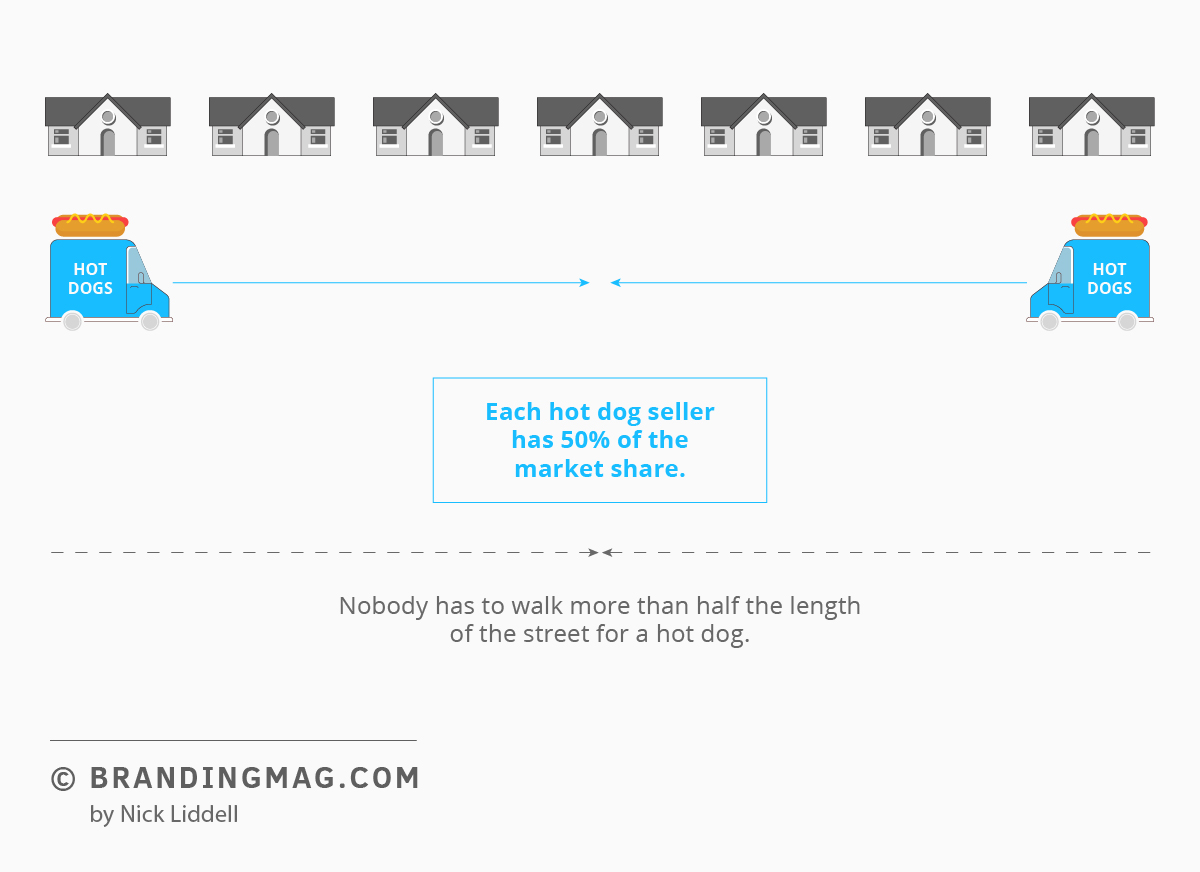

This is where Hotelling’s law comes in. Let’s imagine our entrepreneurs begin at opposite ends of the street. If they stay there, each gets half of the market and nobody has to walk more than half the length of the street to get a hot dog.

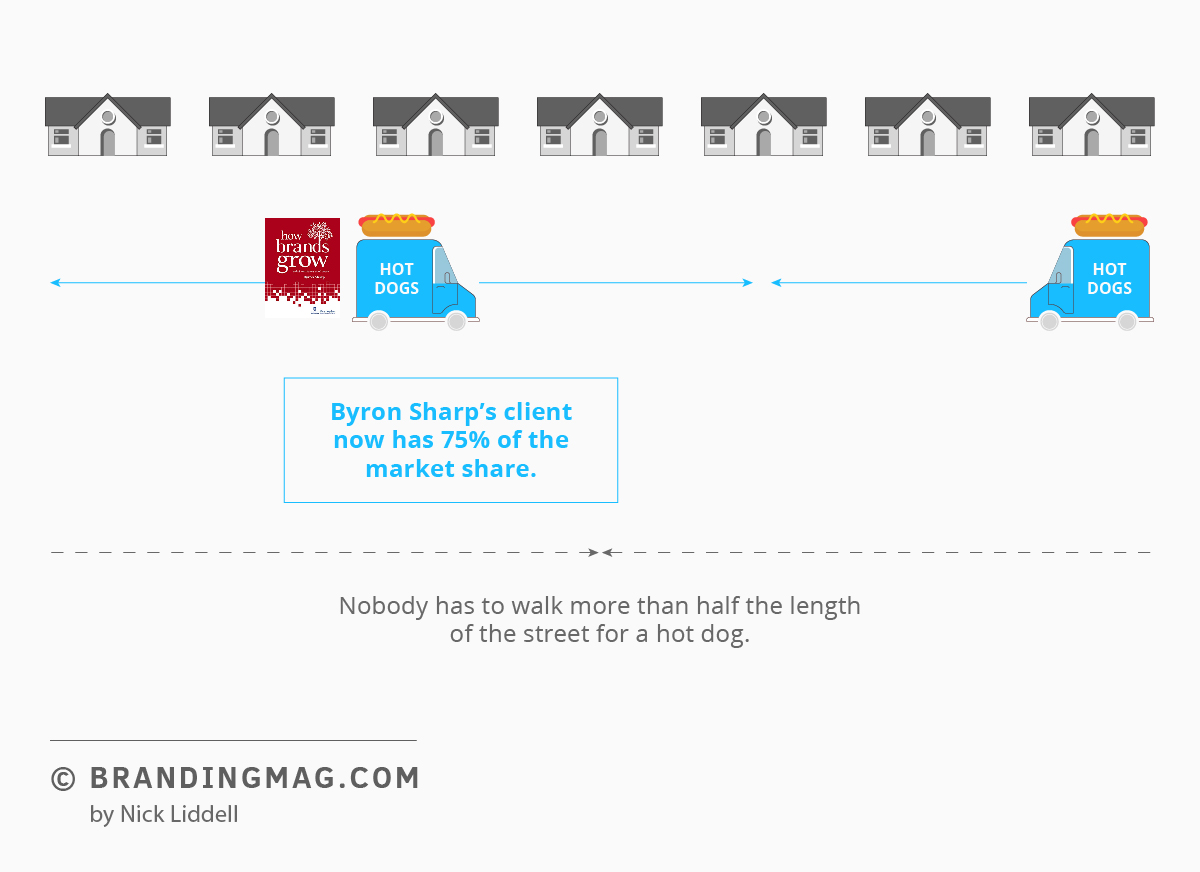

Now, let’s say Byron Sharp is advising one of our hot dog entrepreneurs. His advice would be to nudge closer to the middle of the street to maximize his penetration of the market; not only will the hot dog entrepreneur still capture all of the people who live at their end of the street, but also the closest half of the people who live at the competitor’s end of the street. Their share will grow from 50% of the market to 75%.

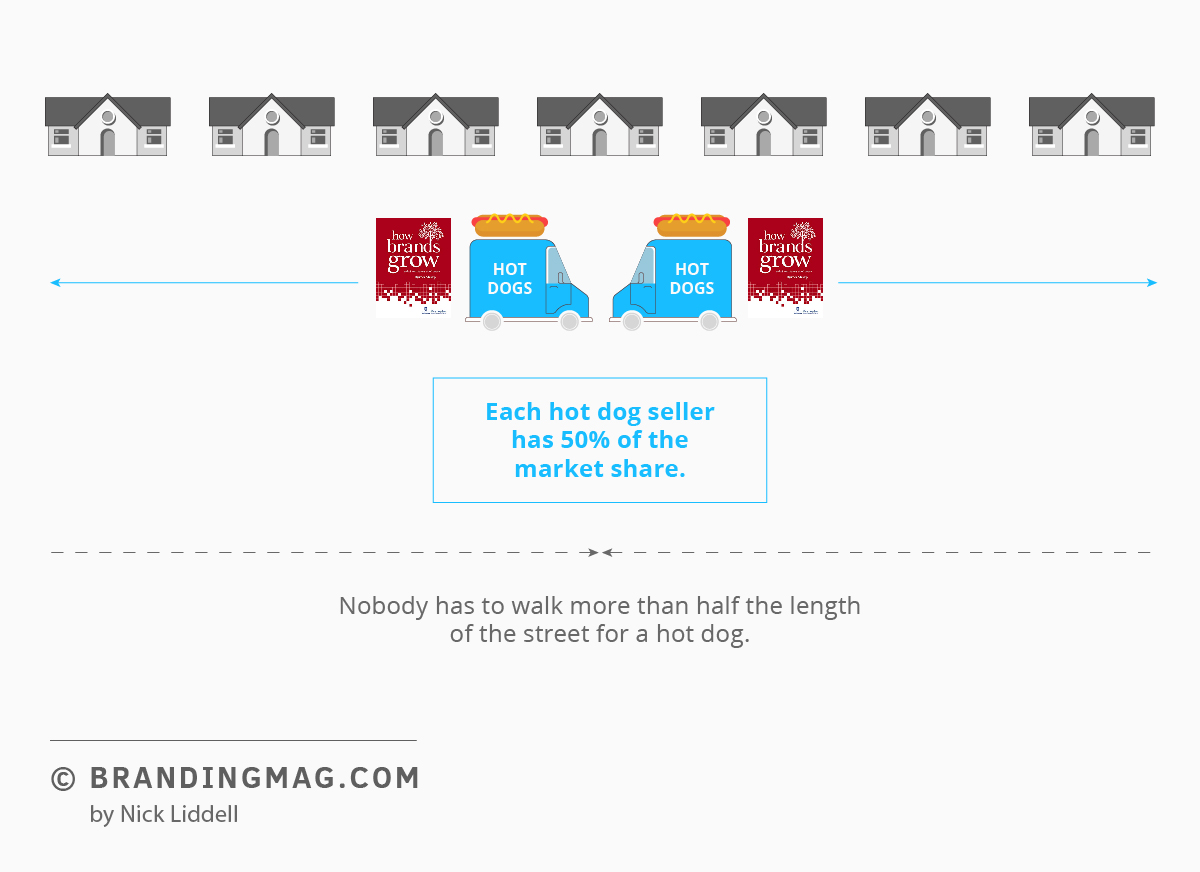

If both hot dog entrepreneurs follow Byron Sharp’s advice, they will engage in a race to the middle. The net result will be no different for each entrepreneur than if they had stayed at their end of the street: Both hot dog stands reach 50% of the market and the furthest anybody has to travel to buy a hot dog is half the length of the street.

If you’ve ever wondered why McDonald’s and Burger King often appear next door to one another, or why sellers of a specific good tend to congregate in the same district, Hotelling’s law explains why. The law doesn’t just apply to place, but can be extended to competition on price, product, promotion, and positioning. Along all these dimensions, capitalistic competitors will tend to gravitate towards the middle of the market. And capitalistic competitors who follow Byron Sharp’s advice will get there quicker than the rest.

What would happen if the hot dog owners were driven by a brand purpose?

There are plenty of definitions of brand purpose, but they tend to involve establishing an ideal that a business should pursue, beyond simply making money.

So, let’s consider what would happen to our hot dog entrepreneurs if they factored social good in their decision-making process.

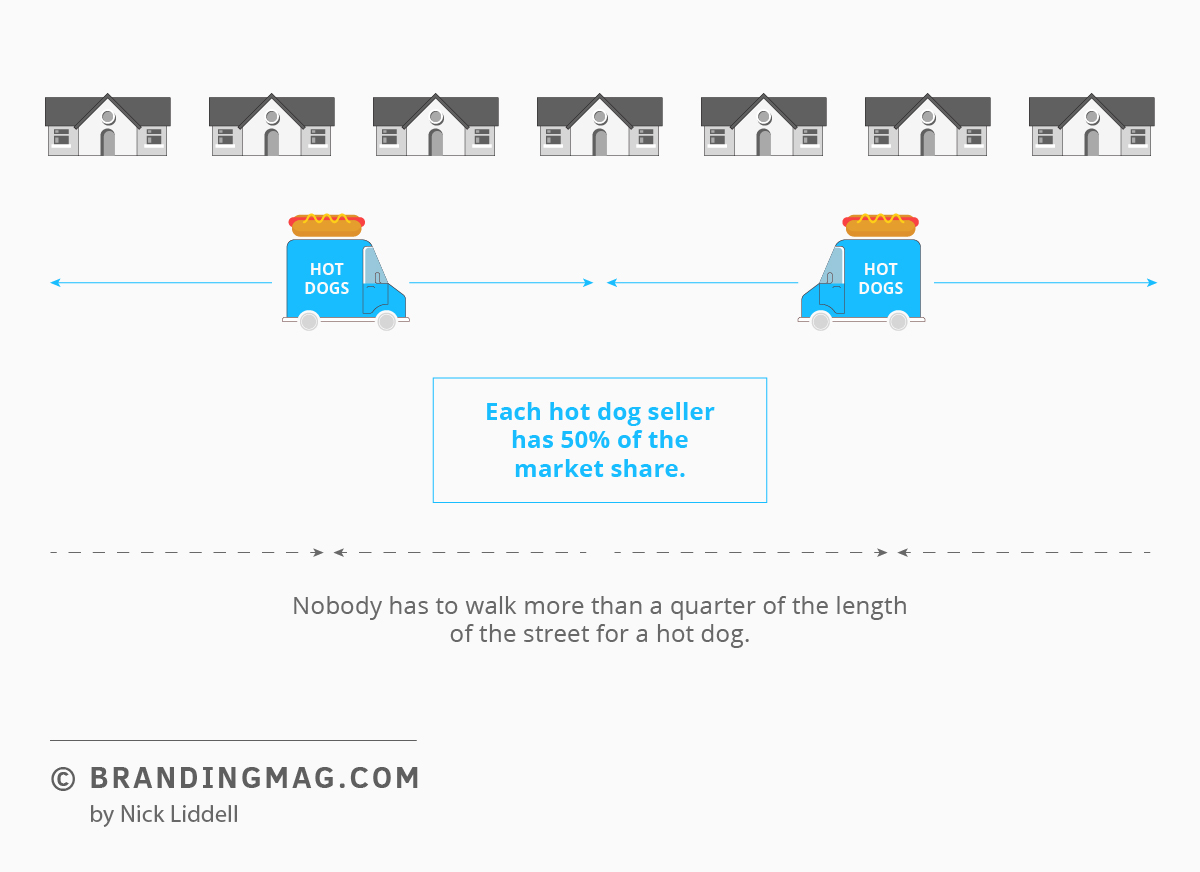

Harold Hotelling’s paper identified the socially optimal position for the hot dog stands: a quarter of the way in from each end of the street. The hot dog entrepreneurs each retain a 50% market share, but the residents as a whole are better-off, as nobody has to walk further than a quarter of the length of the street to buy a hot dog (compared to half the length of the street, in the ‘pure profit chasing’ examples above). If you happen to live at the extreme end of the street, that means your traveling distance is halved.

At this point, each of our hot dog entrepreneurs faces a stark choice:

- If they are purpose-led, then they will continue to position their cart a quarter of a length in from their end of the street;

- If they are led by Byron Sharp’s advice, they will move towards the middle of the street and maximize their reach.

Crucially, they cannot decide to do both: They will either need to sacrifice their social purpose in order to (temporarily) maximize profit, or they will need to risk sacrificing profit in pursuit of their social purpose. Thinking about where you would position your own cart will tell you something about the type of marketer you are.

Building mental availability

This is only one half of the story. Things get even bleaker for our residents if our hot dog entrepreneurs follow the rest of Byron Sharp’s advice. To build physical availability, each day our hot dog entrepreneurs race each other to the middle of the street. So, how else should they compete? According to Byron Sharp, there are only a few key strategies to grow your brand:

- Lower the price – but he considers this ‘self-defeating’ because “a brand needs to grow to improve sales and margin”.

- Improve the quality of the product for the same price – but this is dismissed because it also negatively affects profit margins (“essentially, these two strategies are similar and not attractive”).

- Innovate and bring new or improved, desirable features to the marketplace – however, according to Byron Sharp, “these advantages seldom last long” so it is important to use the ‘temporary advantage’ to enhance his fourth, final, and favored growth strategy.

- Invest in market-based assets – this is where mental availability comes in. The entrepreneurs need to build their brands by developing ‘distinctive assets’ such as their name and logo, their color palette, typographic style, taglines, and graphic language, so that all advertising and marketing can be as distinctive and memorable as possible.

In Byron Sharp’s world, building mental availability through distinctive assets doesn’t require any specific idea, meaning, or positioning (in fact, brand owners are urged to treat brand positioning and identity like “oil and water”). It’s a matter of creating visual and verbal signposts that look and sound distinct from competitors and then consistently using those signposts in every possible hot dog-related setting so that consumers are reminded of your brand – and only your brand – the next time they want a hot dog. So, if our hypothetical hot dog entrepreneurs follow Byron Sharp’s advice, they will avoid lowering prices, improving product quality, or innovating and will instead sell the same hot dogs, but marketed with names, logos, colors, taglines, and packaging that make them distinct from one another.

What about media strategy?

Byron Sharp is characteristically emphatic in his advice:

“In the absence of other evidence, you can assume that high-penetration media also attract their audience more often.”

In other words, the hot dog entrepreneurs should avoid advertising in fragmented, niche media as this not only has the drawback of reaching a smaller number of people than mass media (like TV) but also has the added drawback of attracting that audience less often than the mainstream media.

Where does this leave our street-dwellers?

If our hot dog providers are adherents to Byron Sharp’s laws of marketing, they will be served by two middle-of-the-road, hot dog carts, positioned right next to one another, serving the same types of hot dogs but with distinct names, logos, colors, and packaging. Both brands will be advertised on the biggest TV channels and will shun niche media. And, if you’re unlucky enough to live at either end of the street, you’ll have to walk half the length of the street each time you want a hot dog.

- Neither hot dog entrepreneur will invest in developing a better product.

- Neither hot dog entrepreneur will invest in varying their menu.

- Neither hot dog entrepreneur will lower their prices.

Our residents will be sold exactly the same products, advertised through exactly the same media, positioned in exactly the same space, but with different veneers.

This is more than just a theoretical exercise: It’s a critical issue for any marketer who wants to blend Byron Sharp’s thinking with brand purpose. And much more is at stake than how far a hypothetical person has to travel for a hot dog. Because brands that follow Byron Sharp’s advice place such a strong emphasis on maximising penetration and reach, they inevitably end up in the middle of the market. Rather than creating an ‘astonishing amount of choice’, Byron Sharp’s laws of growth demand a single-minded pursuit of penetration, at the cost of any form of meaningful differentiation.

The inevitable consequence of this prioritization of ‘distinctiveness’ over ‘differentiation’ is that brands will become increasingly disconnected from the diversity of needs, aspirations, and cultural nuances that exist in most societies. The problem is particularly acute the further away from the “middle” or “mass” you happen to be; the smaller your niche, the more “exotic” your minority, the further you sit from the middle of the road, the more likely it is that you will lose out. This isn’t a new problem; it’s been around for centuries and is called the “tyranny of the majority”.

If you think I’m painting an unnecessarily bleak picture of Byron Sharp’s approach to marketing, I’d urge you to read (or re-read) his books. They are unashamedly nihilistic:

- “Many marketing texts talk about creating value, delivering customer satisfaction, and building relationships. This makes the marketing profession appear so much more honorable.”

- “Brands are a necessary evil.”

- “Don’t get caught up in the meaning of it all.”

- “Rather than strive for meaningful, perceived differentiation, marketers should seek meaningless distinctiveness.”

All of this is bad enough if only a handful of brands adhere to Byron Sharp’s growth agenda, but when all the biggest brands in a market follow his advice, it results in groupthink: everybody ends up targeting the same audiences; they all target their products at the biggest needs and the most popular price points; they all sell through the biggest channels; they all compete for access to the most mainstream media. Everybody ends up chasing exactly the same balls. This is wonderful news if you happen to be in the middle of a market, or own a large media platform (which explains why mass-market brands targeted at the middle market and owners of huge advertising platforms tend to be so enthusiastic about Byron Sharp’s work). But it’s absolutely terrible news if you’re anybody else: if your tastes vary from the norm; if you don’t sit in the middle of the market; if you value diversity. And I’m seeing this happen in real-time in the real world.

“Rather than creating an ‘astonishing amount of choice’, Byron Sharp’s laws of growth demand a single-minded pursuit of penetration, at the cost of any form of meaningful differentiation.”

Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that purpose and growth aren’t compatible – countless studies demonstrate they are entirely compatible. What I’m pointing out is that, at some point, you’ll need to decide which matters more: purpose or growth.

Real-world examples of this marketer’s dilemma exist all around us. For example, the current (May 2021) edition of Campaign Magazine features an article about the relative lack of interest in “minority media”. Despite the Black Lives Matter-inspired push for diversity in marketing, the owners and sales teams of radio stations, newspapers, and other media developed for ethnic minorities report that it remains ‘very difficult’ to meet brands and their media agencies – let alone work successfully with them. Christopher Kenna, founder and chief executive of Brand Advance and D.E.C.A. (which stands for Diversity, Equity, Culture, and Action), suggests in the article that a brand’s media spend should be divided in a way that is proportional to the number of ethnic minority people:

“If 9% of the UK is black, Indian, Asian, and multi-ethnic, then 9% of your media spend should go to media that reach those demographics.”

Byron Sharp’s books point brands and their agencies in the opposite direction:

“Media that attract bigger audiences will be used more often and for longer by those audiences.”

In other words, niche media targeted at minority audiences will be used less often and for less time by those audiences than mainstream media, which reach a large, nationally representative cross-section of the population. I don’t doubt the veracity of the advice; based on the available data, Byron Sharp makes a strong case for focusing on mass media rather than smaller, fragmented channels on the grounds of efficiency of reach (what he calls the double jeopardy law). So, the case for investing in these media has to be made on the grounds of purpose.

The article provides the example of Nationwide Building Society, which is guided by a social purpose, and challenged its media agency, Wavemaker, to develop a more diversity-oriented approach to media planning. In response, the agency developed an in-depth “diversity lens” for segmenting its audiences, held inclusive planning and activation sessions, Q&A panels, and arranged speed-dating-style sessions with diversity-owned media partners. The resulting campaign increased overall reach by 8% and 9% for audiences of Pakistani and Indian heritage, respectively. The marketers at Nationwide are almost certainly aware of Byron Sharp’s double jeopardy law; I’m guessing that they simply chose to ignore it in this case in favour of doing the right thing. Purpose won the argument.

And why not?

A desire to introduce more scientific methods into marketing shouldn’t make us blind to the growing expectation that businesses and brands should create value for society as well as for their shareholders. Any quantitative model is limited by the narrowness of the data that feeds it, as well as the assumptions of its creators. If the context around that data changes, the flaws in those assumptions and the model itself eventually bite their users in the arse. Published in 2016, How Brands Grow Part 2 was an opportunity to revise or moderate some of these assumptions, but Byron Sharp and his co-author Jenni Romaniuk instead doubled down. Only five years on, some of the examples and some of the advice is already cringe-inducing:

“Customers do vary a great deal in their lifestyles, interests, wealth, age, and so on. It is easy to get distracted by those differences and make things more complicated than they need to be.”

In other words, issues to do with social injustice and inequality are mere distractions. In a section titled, ‘Don’t shoot yourself with target marketing’, the authors use Goya Foods in the US as a great example of what can be achieved when you avoid these distractions:

“America’s biggest Hispanic-owned food company, Goya Foods, began in 1936 as a specialty distributor of basic products, such as beans, to Hispanic immigrants. Today, it is one of the USA’s fastest-growing food companies, introducing all sorts of Americans to a (wide) range of Hispanic-inspired food items. ‘We like to say we don’t market to Latinos, we market as Latinos’, says Bob Unanue (Wentz, 2013)… Goya Foods [is an example] of marketers thinking about the category needs their brands could satisfy, and worrying less about who within the category is going to buy their brand. This thinking widened their potential markets and created sales opportunities that would have been missed if they had stuck to their ‘target’ markets.”

If you’re wondering what happened next, Bob Unanue visited the White House in 2020, where he took the opportunity to publicly praise then-President Donald Trump, who he described as “a builder”. Perhaps, unsurprisingly, given Donald Trump’s promise to build a wall between the US and Mexico, critics condemned his comments as tone-deaf to the community Goya Foods largely serves, and consumers called for a boycott of the brand. According to an ABC News report, the brand received $47m worth of negative publicity, the boycott intensified, and competitor brands reported sales spikes as a result. With the benefit of hindsight, the Goya Foods case study seems more fitting as an example of the perils of ignoring the public’s expectation that brands should contribute positively to society and pay due attention and care to the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of minority groups.

For a group of researchers so seemingly fond of pointing out others’ stupidity (Starbucks’ CEO is “deluded”, marketers are “arrogant”, and their practices are “medieval”), the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute’s own worldview seems astonishingly bereft of nuance or humility. It’s easy to get the impression they are a vainglorious bunch of academics who enjoy tearing marketing professionals to shreds for having the audacity to believe in important-but-unmeasurable concepts like originality, social conscience, and value-creation. And with a certainty that belies the fact that the data on which they base their opinions is limited and backward-looking. This toxic level of confidence, combined with their general level of disdain for anybody with the temerity to disagree with their worldview, encourages a dangerous and unnecessary form of tunnel vision.

In reducing the role of branding to a single aim – growth – Byron Sharp and the Ehrenberg-Bass institute have simultaneously established the biggest strength and the greatest weakness of their “scientific” approach: The single-minded pursuit of growth might be an appealing message for CMOs grasping for “scientific” credibility; but it also absolves them of responsibility for important activities that should be a part of their job description, such as ensuring their businesses anticipate and respond to important changes in society, including the continuing struggles against systemic racism, climate change, and social inequality.

If the Lindy Effect is anything to go by, the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute and its scientific marketing approach will still be here in another ten years’ time. By the same logic, the tyranny of the majority and its associated ills will be around a great deal longer than that. It’s not enough to dismiss these issues as a mere distraction, or to pretend they exist outside the remit of brands; nor is it helpful to suggest that marketers and brands are acting with arrogance in acknowledging these issues and taking positive steps to making society healthier, happier, and more sustainable. If marketers aren’t part of the solution, then we will continue to be part of the problem.