“Things are not always what they seem; the first appearance deceives many; the intelligence of a few perceives what has been carefully hidden.” – Phaedrus

This article is a direct follow-on from Part 5.1 where we explored the story behind Apple’s famous “Think Different” campaign and discussed why it’s important to analyze. At the end, we briefly looked at the company’s financial performance during the campaign’s lifecycle (1997-2002).

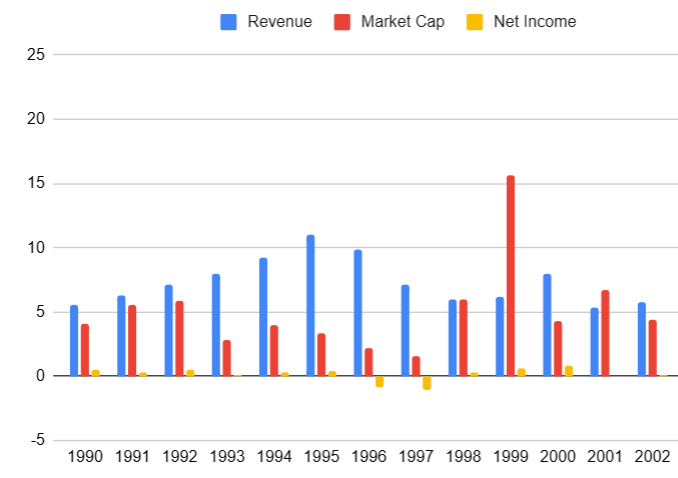

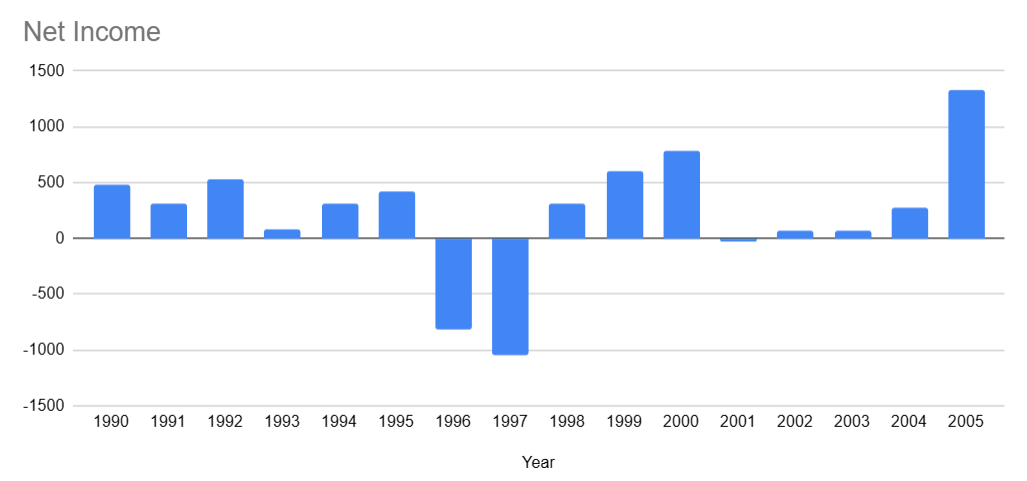

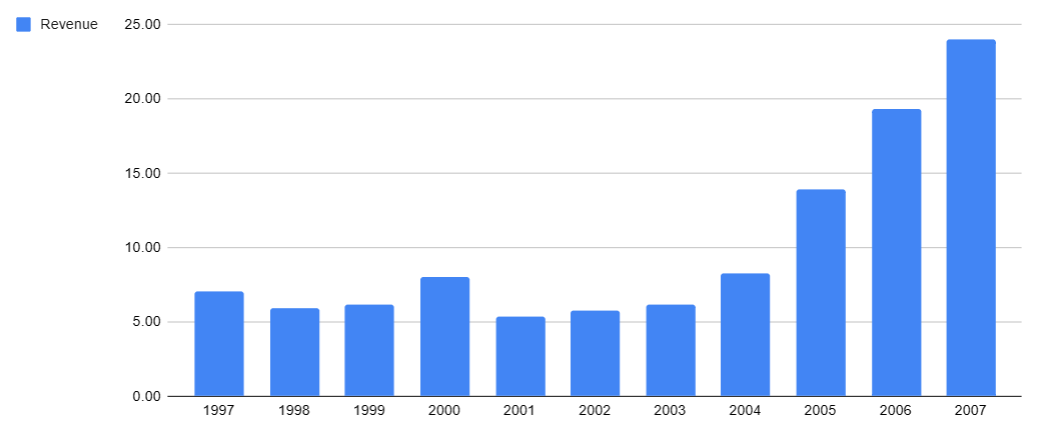

When shown this graph, most marketers would say:

- Market capitalization increased–look at 1999!

- Profit was positive for 3 years after 2 negative years

- Revenue stabilized and then increased in 2000

- Brand campaigns can have long-term trailing effects that are not easily measured. Look at Apple’s performance after 2002; they’re now one of the biggest companies in the world!

These are all fair points, so let’s go through each and have a closer look.

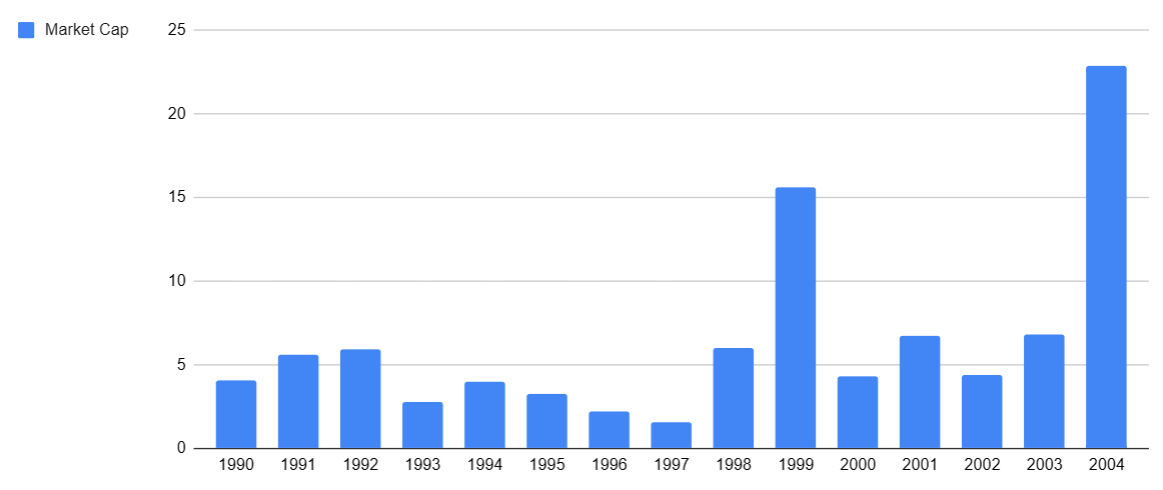

1. Market capitalization increased

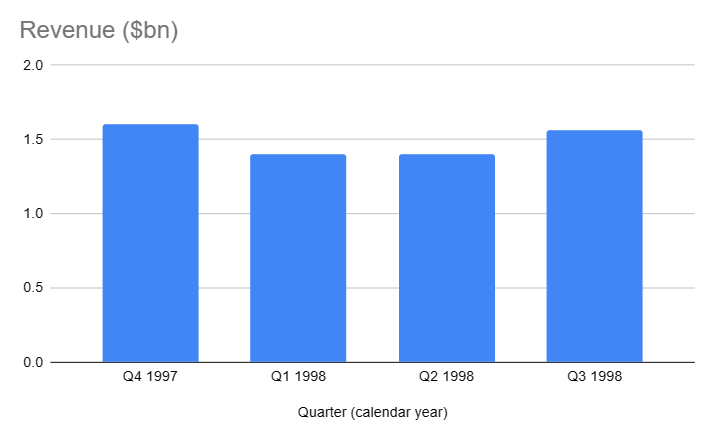

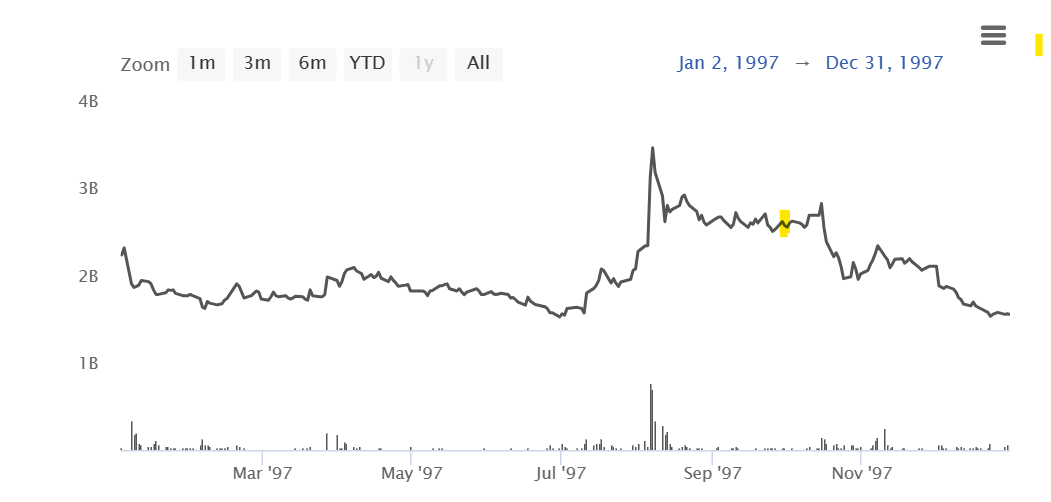

Market capitalization is the current public value of a company (number of shares multiplied by the price of one share). If you thought “Think Different” had a big impact on Apple’s market value in the short term, then you’d be wrong. In the last quarter of 1997, Apple stock lost $0.5bn in value, finishing at a low of $1.6bn.

If you prefer visuals, here’s the graph with yellow highlighter used to show when the “Think Different” commercial first aired:

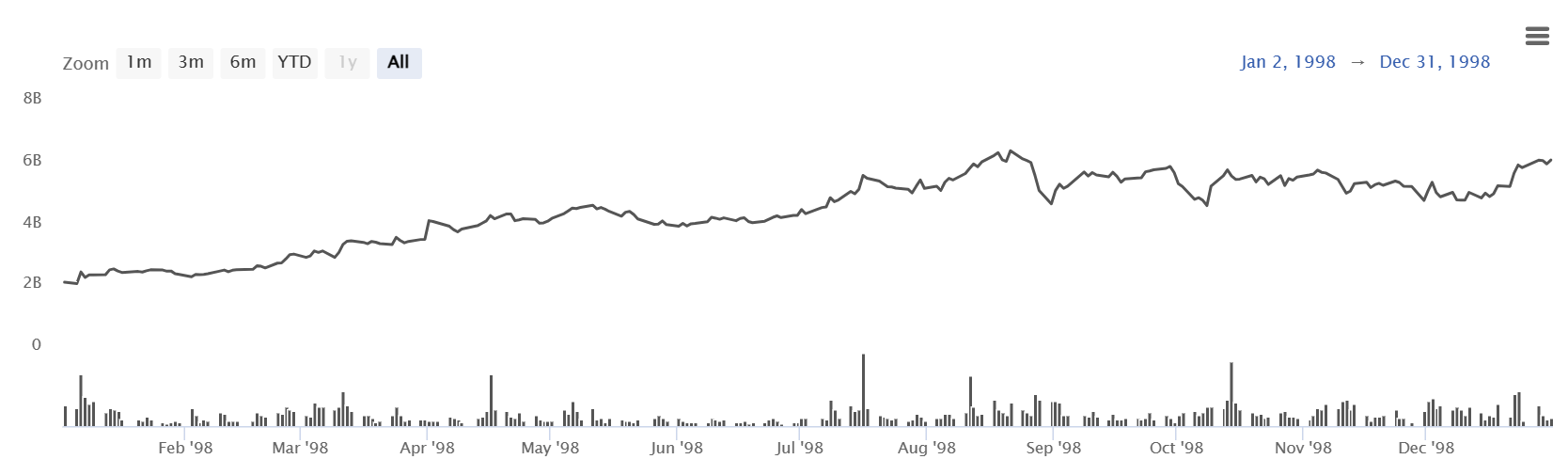

1998 was a better year. By April, financial results were back to 1997 highs, and the year finished at $6bn–roughly a 3x increase. Let me guess: This was a delayed effect from the brand campaign, right?

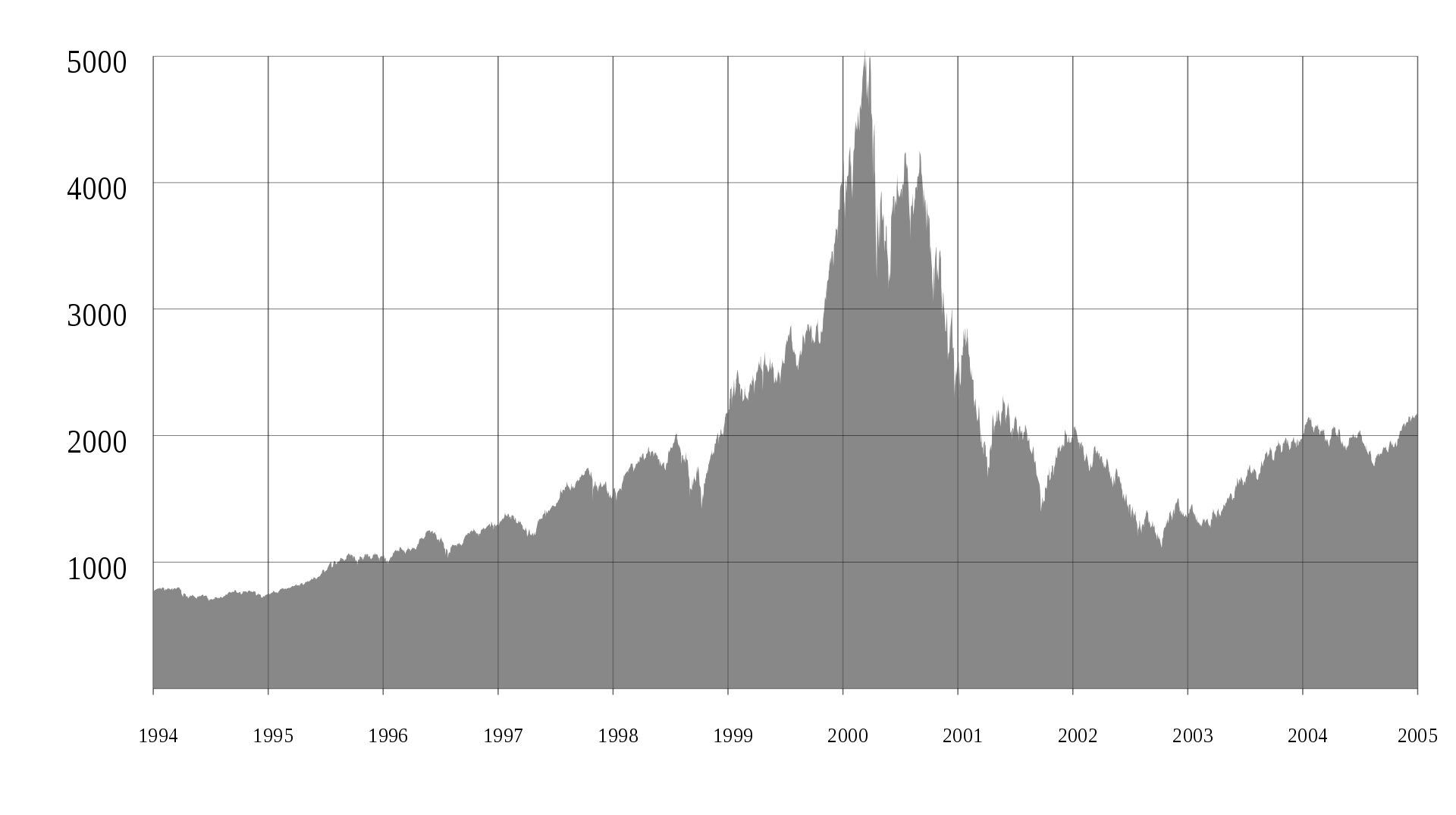

The next year, market cap more than doubled to $15.6bn (1999) before crashing back down in 2000, where it would stay in a holding pattern until 2004.

By looking at these figures we could easily argue “Think Different” was the reason for this rise in market cap. And that might be true if it wasn’t for something else that just happened to occur at exactly the same time. The Dot-Com boom and bust. This sector-wide cycle affected tech stocks–especially the more speculative ones–heavily. Even Amazon nearly went out of business with a share price that cratered 90% in 2001 (see below).

Rival Microsoft shows a similar shape. Note the same peak in 1999/2000.

And then, there’s Apple.

In fact, most speculative tech stocks on the NASDAQ during this period show a similar trend: a boom that peaks in 2000 before retreating to a low in 2001.

Keep in mind that Apple’s earnings were relatively flat during this whole period (see the chart earlier), so this sector-wide halo effect could explain a good portion–if not all–of the boom Apple experienced in its market cap. Steve just seems to have timed his return perfectly to catch the tail end of this uptick.

“My life is all about timing. As a comedian, my sense of timing is everything.” – Jerry Seinfeld

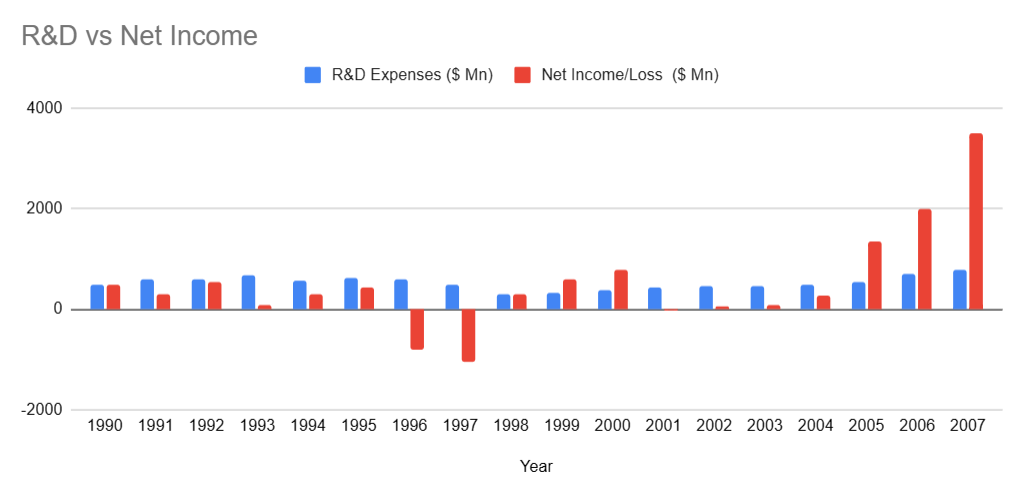

2. Profit increased in 1998 and 1999

It’s also tempting to look at the profit figures and believe “Think Different” was the reason Apple could post 3 years of profitability. That might be true if not for the way net income is calculated (a factor of both revenue AND expenses).

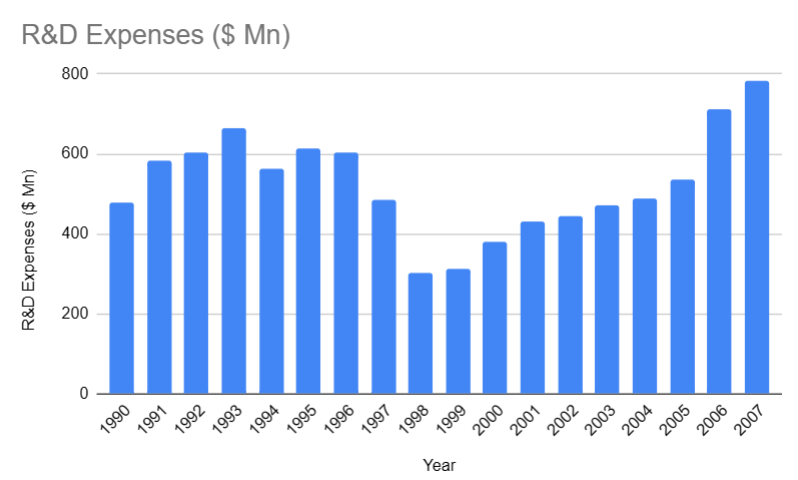

At exactly the same time when the “Think Different” campaign rolled out, three major events occurred that heavily affected net income. The first was a heavy cut to research and development (R&D) budgets, particularly in 1998 and 1999. These cuts dragged on until 2006 (see below).

The reason behind this change is confirmed via public 10-K disclosures (SEC filings).

“The declines in total expenditures for research and development in 1999 and 1998 as compared to 1997 were principally due to restructuring actions…intended to focus the company’s research and development efforts on those projects perceived as critical to the company’s future success.”

The second was a reduction in payroll from employees that were let go–over 4100 of them, to be more specific. If the average salary was $100k, then that reduction would amount to over $40m in savings per year.

And the third was a $150 million cash injection in late 1997 which, ironically, came courtesy of rival Microsoft. This deal operated similar to a convertible note. Microsoft had to hold onto these “preferred shares” for 3 years at which point they could cash out if they wished. Most important, however, is that this investment came with a number of distribution perks.

Distribution, the forgotten P

If you agree with Byron Sharp that mental availability is key to brand growth, then you can’t ignore the importance of the other half: physical availability. As we learned in Part 3, making a product easy to find and buy is critical to advertising’s success.

Included in the aforementioned agreement were provisions for broad patent cross-licensing. Microsoft promised to support a Microsoft Office Mac edition for 5 years. In exchange, Apple agreed to make Internet Explorer the default web browser on the Mac.

In November 1997, Apple also announced they’d start selling computers directly, both over the web and phone. During the iMac product release tour in 1998, they also announced that CompUSA would be their new distribution partner for physical store sales.

And if you think these details are a minor growth factor when it comes to revenue, think again. Google’s recent antitrust hearings reveal just how important distribution deals are, and we’d be wise to take note.

These are the key paragraphs of (threat) letter revealed yesterday from Google to Microsoft when it found out MSFT would make its search engine the default in its new browser. Google’s statements on power of defaults vs user choice undermine much of its defense to date. /2 pic.twitter.com/off6JkrBAS

— Jason Kint (@jason_kint) October 31, 2023

Google reportedly paid Apple $27.5bn for this privilege in 2021, and some analysts argue their entire business model would have collapsed without it.

The deal Apple struck with Microsoft in 1997 not only boosted distribution but also made Microsoft customers less adverse to switching to Apple (because they didn’t have to learn new software). It also gave Steve some earnings breathing space with $300m or so in R&D savings, another $150m from the share sale, and another $40m or so from staff expense savings.

After 2 years of large loss, these savings were leveraged to deliver a $309m profit in 1998–very important from a governance perspective. This profit helped reassure investors that the company was not only liquid but well on the path back to growth and profitability.

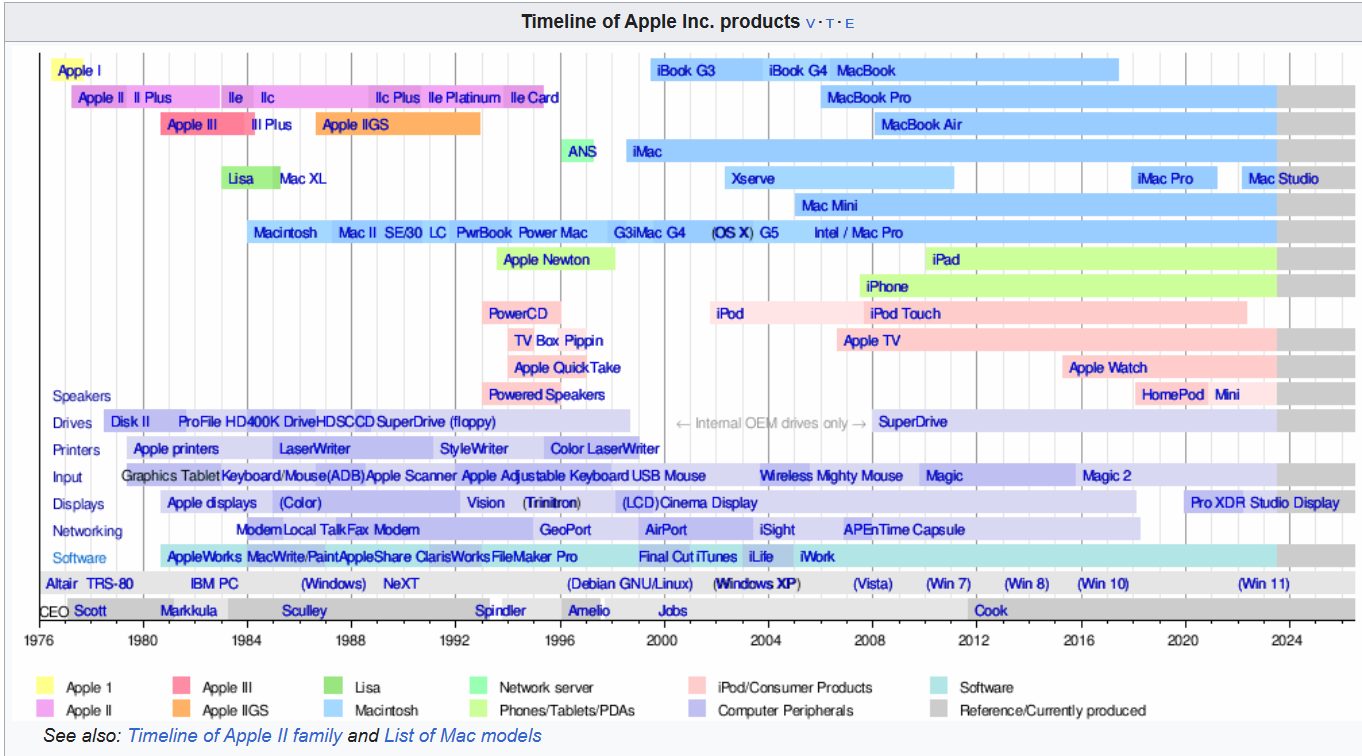

Apple didn’t release any new products for 10 months either. Instead, they focused on harvesting as much revenue as they could by clearing out existing inventory with the added help of product-specific promotional efforts.

But, even with all these measures and a famous brand campaign running in the background, Apple struggled to maintain profitability. As the graph below shows, net income even went slightly negative again in 2001!

In other words, it appears “Think Different” didn’t have any significant or prolonged impact on profit.

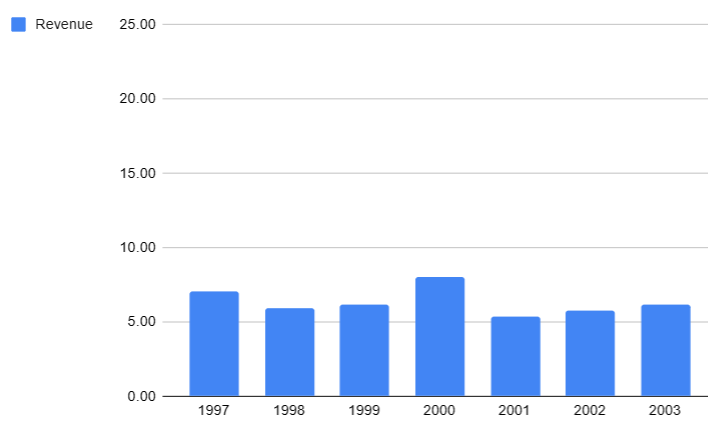

3. Sales revenue increased from 1998 to 2000

There was a mild upward trend in revenue, but this was mostly due to the introduction of 3 new products in late 1998. At the same time, we can’t discount the effect cuts to the product portfolio had on top-line revenue either. Reducing products from 14 to just 4 most likely reduced income in the short term even if it did help profit margins. A timeline of product life-cycles below shows a noticeable white gap where the product portfolio was changed (see the middle of the graph).\

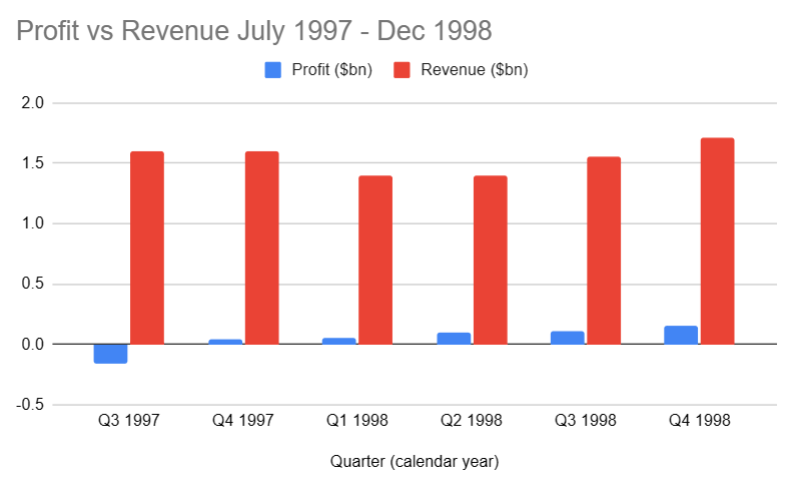

To be frank, revenue doesn’t show any significant spike throughout the entire lifecycle of the “Think Different” campaign. And remember, the bulk of this media spend occurred between Q4 ‘97 and Q4 ‘98. So, if the campaign’s brand influence was meant to translate into positive long-term impact years down the track, then when exactly was that supposed to happen?

Here’s a quarterly breakdown for the period where the bulk of the media spend for “Think Different” was active.

In other words, there doesn’t seem to be any significant short-term effects from the campaign either. Revenue did finally increase but only in 2002, years after “Think Different” stopped being used altogether!

So, what caused revenue to spike from 2004 onwards? Was it the result of a residual, long-term “brand effect” from the “Think Different” campaign or something else? There’s one reason which very few marketers talk about, but we’ll get to that in a minute. Before we do, we must discuss another growth factor that even fewer marketers talk about.

Paid media advertising wasn’t the only promotional effort Apple was running at the time. Apple was heavily using another marketing channel that all advertising commentators conveniently forget to mention. Why? Because it’s something they don’t sell, and it’s invisible to the untrained eye.

Lights, camera, action!

When Steve exited Apple in 1986, he also became a majority shareholder in a company called Pixar. This allowed him to rub shoulders directly with George Lucas and other powerbrokers in Hollywood.

Upon Steve’s return, Apple increased their investment in a channel that ended up being one of the most potent arrows in their promotional quiver. Something that continues to this day. They started supplying film studios with props for filming, aka product placement. This wasn’t anything particularly new because their first product placement took place in the 1986 film Short Circuit.

But when Steve returned, he significantly increased investment in this channel given that he now had all the film industry contacts to make it happen (Pixar). Product placement isn’t just far less costly than traditional advertising, it also has the added benefit of showing the product in use while simultaneously leveraging associations with famous celebrities. This means it doesn’t only provide reach; it also inserts the brand within popular culture (something your typical ad campaign rarely achieves), thereby building fame like no other channel can.

Cue the “the files are in the computer” scene from Zoolander:

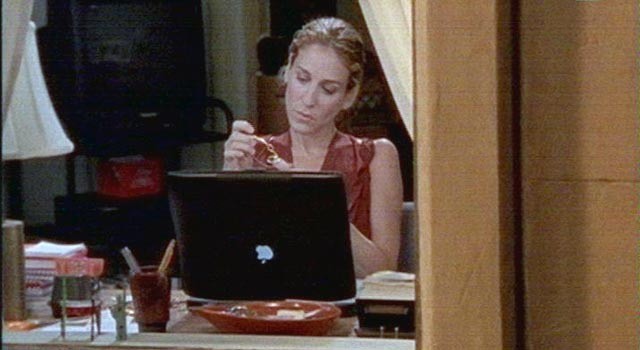

And this scene in Legally Blonde, which is basically a giant ad for the iBook:

Associating iBook with an atypical Harvard law student like Elle was a deliberate brand positioning play. Apple was targeting an underserved, female computer-user segment previously alienated by technical, gray, clunky box designs. In other words, they targeted affluent women who thought and bought “differently”.

Both films in 2001 became very famous and commercially successful, giving the brand hundreds of millions of quality impressions worldwide. Apple’s brand was quickly becoming young, hip, rebellious, modern, and inclusive. And once filming finished, guess which computers a bunch of influential film industry folk took home to use?

“The best marketing doesn’t feel like marketing.” – Tom Fishburne

But these two movie deals were just the tip of the product placement iceberg. Apple products have since appeared in hundreds, if not thousands, of movies and TV shows over the years. And it’s an effort that continues to this day. (There’s even a top 14 list, in case you’re interested.)

Product placement is so important to the brand that they even turned the logo upside down, so it would appear correctly for viewers!

If you’re a fan of Sex and The City, you probably haven’t realized just how many Apple products feature heavily (and exclusively) throughout the series. But, while this is one of Apple’s most powerful marketing channels, it seldom gets talked about–especially by marketing commentators. Why? Because promotional channels like publicity, product placement, direct marketing, and sales activation all cut a paid media agency’s lunch. These channels are also less scalable and require more skill to execute even if they are more commercially impactful. And as we learned in Part 2, vendors have difficulty building lucrative business models around these forms of promotion.

4. Brand campaigns have long-term trailing effects that aren’t easily measured

Apple’s financial results don’t show any clear or significantly large improvement as a direct result from the “Think Different” campaign. Which brings us to the number one excuse brand marketers give when quizzed on commercial impact: Brand campaigns have a long-term lingering effect that can take years or even decades to materialize.

Maybe this is true, and we’re looking at too short of a timeline. Perhaps, we need to go beyond 5 years and consider all the secondary and tertiary effects from the campaign, too. But how do we tell the difference between someone using that argument as an excuse for an underperforming campaign versus an effective campaign having subtle and sustained impact over a long period of time?

Yeah but…

…it needs more time in market

…it needs more budget

…we are yet to roll out TVC Version B

…we haven’t launched the ‘activation’ yet— Everard Hunder (@everardhunder) November 27, 2023

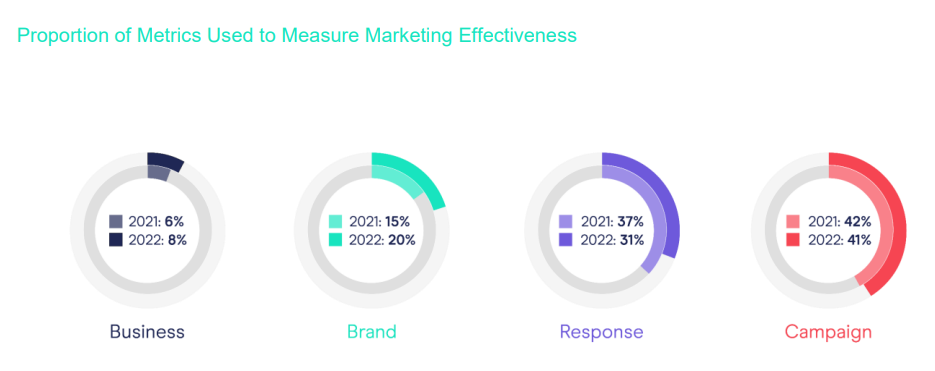

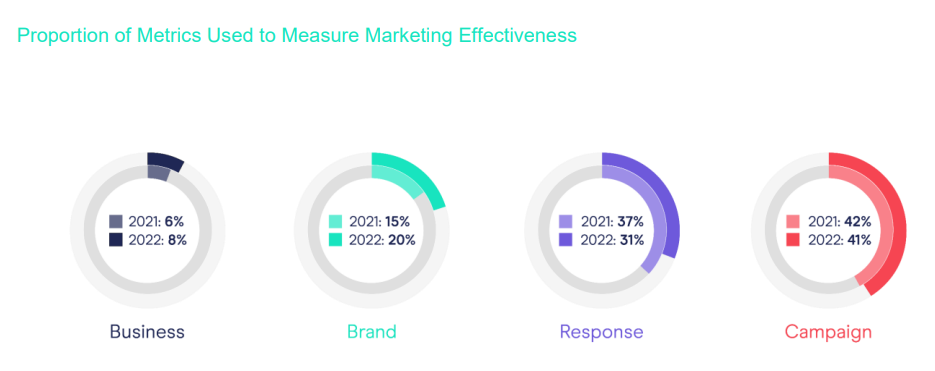

It’s only natural for everyone to avoid revenue accountability (especially if revenue comes in below expectations and is dependent on multiple variables), but you can’t have it both ways. You can’t claim responsibility for the brand campaign when results are good and avoid blame when results are poor. This avoidance of bottom-line accountability, however, is rife and popular within the marketing populace. Check this out:

It reminds me of an industry joke a consultant told me many years ago: “I worked in product to avoid sales. Then, marketing to avoid product, brand to avoid marketing, and now, I’m a consultant. Soon, I’ll be CEO.”

If you’re a brand marketer that wants to avoid accountability, then better that you rely on extending out the performance expectations as far as possible in the future–ideally, beyond the tenure of the average marketer.

Something Ross Sergeant knows all too well. He has a unique take on this issue having worked on brand and media measurement with Asahi after stints at some of the largest media agencies in the world.

“I worked in media agencies. Big and fantastic media agencies…but we had one side of the pie. We also didn’t have the accountability at the end….we were working really, really hard to change perceptions of brands. We weren’t necessarily trying to change behavior. It’s not an OMD thing, it’s just an advertising agency big media piece….

Now, I work at Asahi… We’re looking at our sales over the last year–reported 18 months later. So, if you can’t see a change by then, exactly how much of a long-term view were you hoping to go for? Because 5 years is probably longer than any of our tenures!”

What is marketing effectiveness anyway?

DMA’s 2022 report revealed marketers were using over 178 different metrics to measure their impact. And for 92% of them, commercial metrics didn’t even come on the radar.

Some brand marketers will argue commercial returns aren’t the point of brand investments. That the brand is a bigger construct that transcends all else, and building it takes time, so you just have to be patient and maintain a long-term view. According to copywriter Justin Oberman, there’s a small problem with that approach…

“Brand campaigns aren’t often directly commercially successful because that’s not their point. ‘Think Different’ is a brand campaign that’s wrapped up in direct response. Because the campaigns that followed were product-focused direct response campaigns. Especially the ‘I’m a Mac, I’m a PC’ ads. Those are straight out of the direct response advertising textbook.

So ‘Think Different’ wasn’t supposed to be commercially successful. It was about establishing the way people look at Apple. This campaign set the tone for the direct response campaigns that came after. And there’s no question those campaigns didn’t generate sales.

They [the campaigns that followed] were direct response campaigns wrapped up in brand, which to me is the best form of advertising. Whether it’s around that way or reverse [branding wrapped up in direct response], it doesn’t matter. You need both. Brand campaigns done well, again, have a direct response element in them.”

He goes on to mention how ridiculous this separation between brand and “performance” investments is–something we discussed in detail in Parts 1 and 3 of this series.

“They really shouldn’t be viewed separately. You’ve got to remember even as far back as the 60’s people weren’t thinking in this dichotomy. They weren’t thinking, this is a brand awareness campaign or this is a direct response campaign. That didn’t come until the 70s or 80s.

That’s why the advertising in the 60s was so good and so effective because people just thought how do I sell? Not, oh this has to be brand awareness and this has to be direct response. They would just do campaigns that did both.

This is what Apple did with ‘Think Different’ [and the promotional work that followed]. It’s good for what they needed to do at the time. But it’s also not something to model off if your goal is to increase sales.”

But none of that helps if we’re creating a business case for executives. Take this tweet from Everard Hunder as an example, where he states a reality few want to acknowledge about any brand investment:

Dear marketers. Just to be clear. Building a brand still means generating leads and sales. We are not investing in some abstract concept for the hell of it. We are building a brand to generate more sales and to increase the velocity of those sales via trust and confidence.

— Everard Hunder (@everardhunder) January 4, 2019

And remember this quote from Jenni Romanuik in Part 3? “…and if marketers could stop claiming it is a good thing to spend large amounts of money on advertising that is not aimed at generating sales (short or long term) – that would help too!”

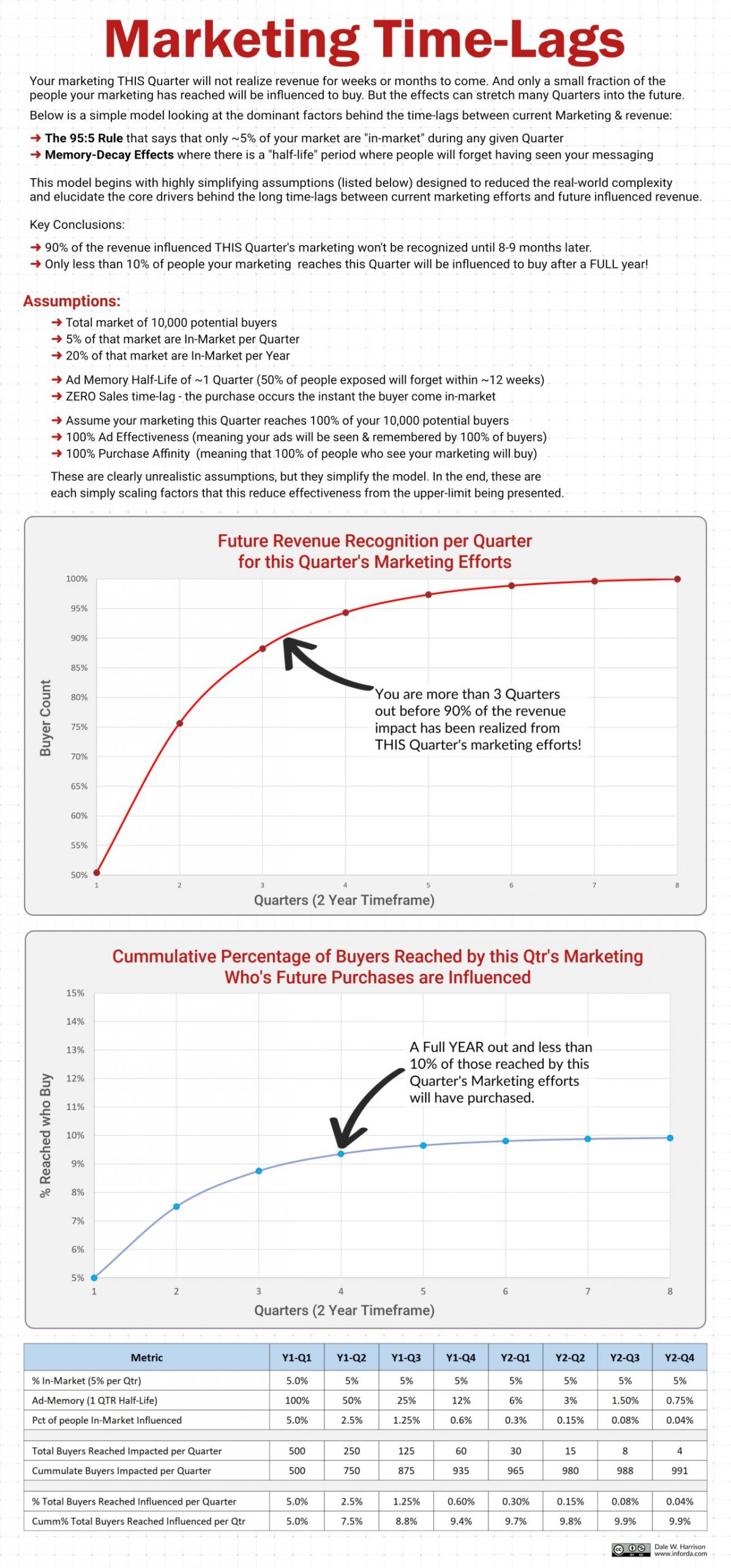

So, the question becomes less about whether brand campaigns should contribute financially or not to the business (they should) and more about over what timeframe we should expect their commercial impact. And how quickly these effects will degrade as memory of your advertising degrades and sales cycles bring customers closer and further from acting on those memories.

What’s a Birkin? pic.twitter.com/gS1uheWA0s

— John James (@adoseofjohn) November 30, 2023

As you’ve probably observed, this is a divisive reality for many to digest within the industry. And people working in the industry remember these ads a lot more than the average consumer ever does–a bias that’s hard for marketers to reconcile.

So, I reached out to a few seasoned professionals known for their marketing, brand, and finance prowess to garner some relevant perspective. When asked how long we could expect brand campaign effects to impact the bottom line, they said:

Alastair Thomson (CFO)

“Arguably for brand campaigns it’s ‘for ever’, but I always like a technique we used in my old direct mail days called half-lives…and that is the acceptance that you’d get 50% of the ultimate response pretty quickly and the rest would come in dribs and drabs in a long tail.

As long as you hit the 50% in 14 days, the campaign was judged a success. Everyone accepted the rest would drift in over weeks and months (and, in practice, that was broadly true). So, without knowing the industry or the campaign, I’d think about what you’d expect the half-life to be and use that as a way of measuring success, given that the long tail is pretty much infinite. After all, I can still recall advertising campaigns from the 70s and 80s!”

Tom Lewis (CFO)

“Brand effects are usually best measured over 6 months to 3 years. Any less and it is more of an activation campaign. It’s hard to measure anything longer, but positive effects are probably still happening to this day. There are so many variables that it’s almost impossible to establish impact unless you build measurement into the campaign from the very start. Quality of creative has to be a factor in longevity of impact; people are still influenced by Sex Pistols nearly 40 years after their last (and only) album.

To quantify this properly, you really need some econometric modeling. As the saying goes, 100% of people who confuse correlation with causation eventually die. Econometrics seeks to identify causation based on the following questions:

- Does A cause B?

- Does B cause A?

- Does a third factor, C, cause both A and B?”

Mike Taylor

“The way you estimate this in a marketing mix model is through what’s called ‘adstocks’, where the impact of the brand campaign decays exponentially over time (because people forget). For example, for a particularly strong brand campaign you might see 50%-60% of the impact carry over from one week to the next, so a campaign that drove $100k in sales in week 1 might drive $50k next week, $25k the week after that, and so on until it’s barely noticeable at under $200 in impact by week 10.

Every channel is different. Something like Google Ads is not very memorable and, therefore, has close to zero adstock. Video ads on social media are in the 10-30% adstock range and brand TV ads are among the most memorable campaigns, sometimes achieving 40%+ carryover.

Of course, it also depends on the creative because some ads are just more memorable than others, and repetition can also reinforce those memory structures, thereby ‘topping up’ the long-term brand effect.

While ‘Think Different’ is certainly memorable to marketers, what matters is how memorable it is to consumers, and I think you’d struggle to find any evidence that the campaign is anything other than a rounding error on Apple’s sales today, two decades after it stopped running.”

Edgar Baum

“For starters, please don’t ever attribute brand campaigns as the sole reason for financial performance, especially immediate near-term financial performance. With that in mind, brands are built holistically, not just through advertising and marketing. The promise conveyed needs to be experienced in the use of the product or the delivery of the service. Any brand campaign needs to express that expectation of what it will be in the hearts and minds of the buyer when it is NOT being used, and is likely NOT to be bought immediately.

Brand-building cycles are longer than buying cycles which are longer than marketing cycles which are longer than sales cycles or consumer purchase cycles. Most critically, what share of the customer base is in the midst of buying/implementing versus currently/recently consumed without an immediate expectation of buying again versus anticipating a near-term purchase?

The effect of brand needs to be measured across all 3 types of buyers and the brand effect is not equivalent with all 3. If you want a rule of thumb (which I hate), 6-8x the length of a sales cycle in B2B, 2-3x the consumption cycle in consumer durables and infrequent services, 12-20x the consumption cycle in consumer perishables/frequent services (since you’re looking to win share of consumption not exclusivity of purchase).”

Secondary research into the residual effects of ad campaigns

Remember the quote from Jenni Rommanuik that said brand-building campaigns are one of the biggest own-goals of the advertising industry? Keep that in mind while reading these studies which investigate the trailing effects from ANY advertising campaign (brand, direct response, activation, sales, etc.).

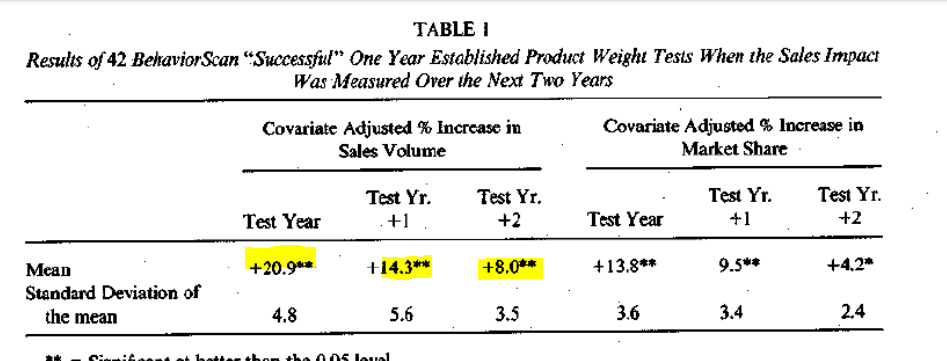

The first comes from Len Lodish who conducted a lot of research into the CPG/FMCG sector. The table below summarizes findings from one such paper that comes from a very large body of work on this topic. It shows a mean sales increase in the first year of advertising campaigns of 20.9%, 14.3% in the second year, and 8% in the third. So, even if your advertising has stopped running, the carryover effect on sales can be significant, but it decays at a rate of roughly ~30% year over year.

Given this, we could reasonably expect “Think Different” to have some positive effects past 1999 and to a lesser extent into the period between 2000-2005. And to a residual but far lesser extent (i.e., a percentage point or two at most) in the years thereafter. Remember, the campaign mostly ran in 1998 before other campaigns took over in the years that followed, and it was pulled out of circulation completely in 2002. Which means that if you argue “Think Different” somehow accounted for a spike in revenue that started in 2004, you have quite the weak argument.

Other studies have found an even shorter residual sales effect. In 2009, Sharp, Kennedy, Taylor, and Newstead investigated the long-term sales effects of advertising. “From very different approaches, two common findings emerge: If advertising is to be sales effective in the long term, it must first work in the short term. Advertising typically has a half-life of three to four weeks.” This study is perhaps even more important to our discussion because “Think Different” didn’t seem to have any short-term positive effect at all.

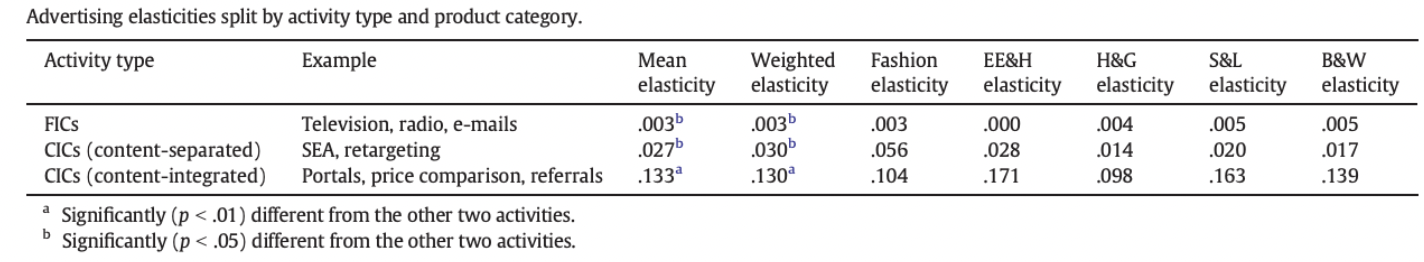

Both studies mentioned above would come as little surprise to Koen Pauwels. A recent paper he was involved in showed that the media we associate with brand campaigns (TV, radio, outdoor, etc.) is actually least effective at generating sales. Even more significant were the findings within the electronics, entertainment, and hardware category. This is the product category Apple belongs to, and it shows the lowest elasticity of them all (0.000)!

According to Pauwels, “Advertising effectiveness continues to be misunderstood, including Freakonomics podcasts popularizing the low and uncertain individual-level effects of TV Advertising and Digital Advertising… What matters is whether we can prove beyond reasonable doubt that our advertising investment has increased our sales performance, and by how much…

Table 6 from ‘The effectiveness of different forms of advertising’ shows how the % sales increase for a 1% increase in advertising (‘advertising elasticity’). We grouped the many ad forms into 3 categories:”

This study also debunks a common narrative within agency circles that offline broadcast mediums are somehow superior to online or “performance” channels. “Online advertising triggered by consumer action (CICs) is 10 times more effective than offline advertising. In every of the five studied categories, online advertising is more effective than offline advertising. However, we see a substantial benefit of content-integrated online ads: They are over 4 times more effective than content-separated ads. Doubling spending on content-integrated ads gives you over 13% sales increase,” argues Pauwels.

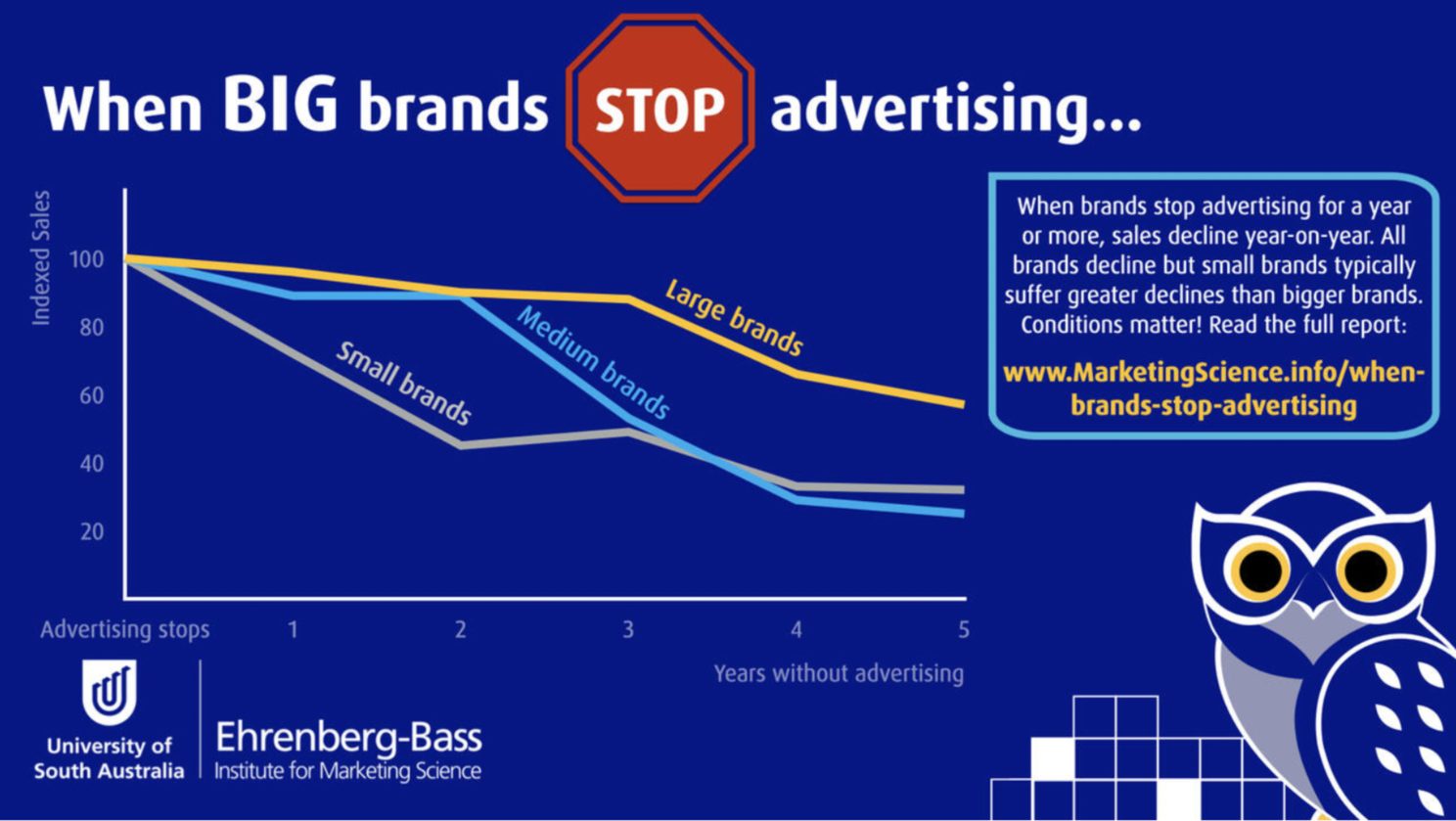

But stagnating revenue figures doesn’t necessarily mean the advertising wasn’t effective. This is because we need to consider the null hypothesis, too. In other words, what would sales be like without the campaign? Luckily, there is empirical research that compares the effect of advertising versus not advertising.

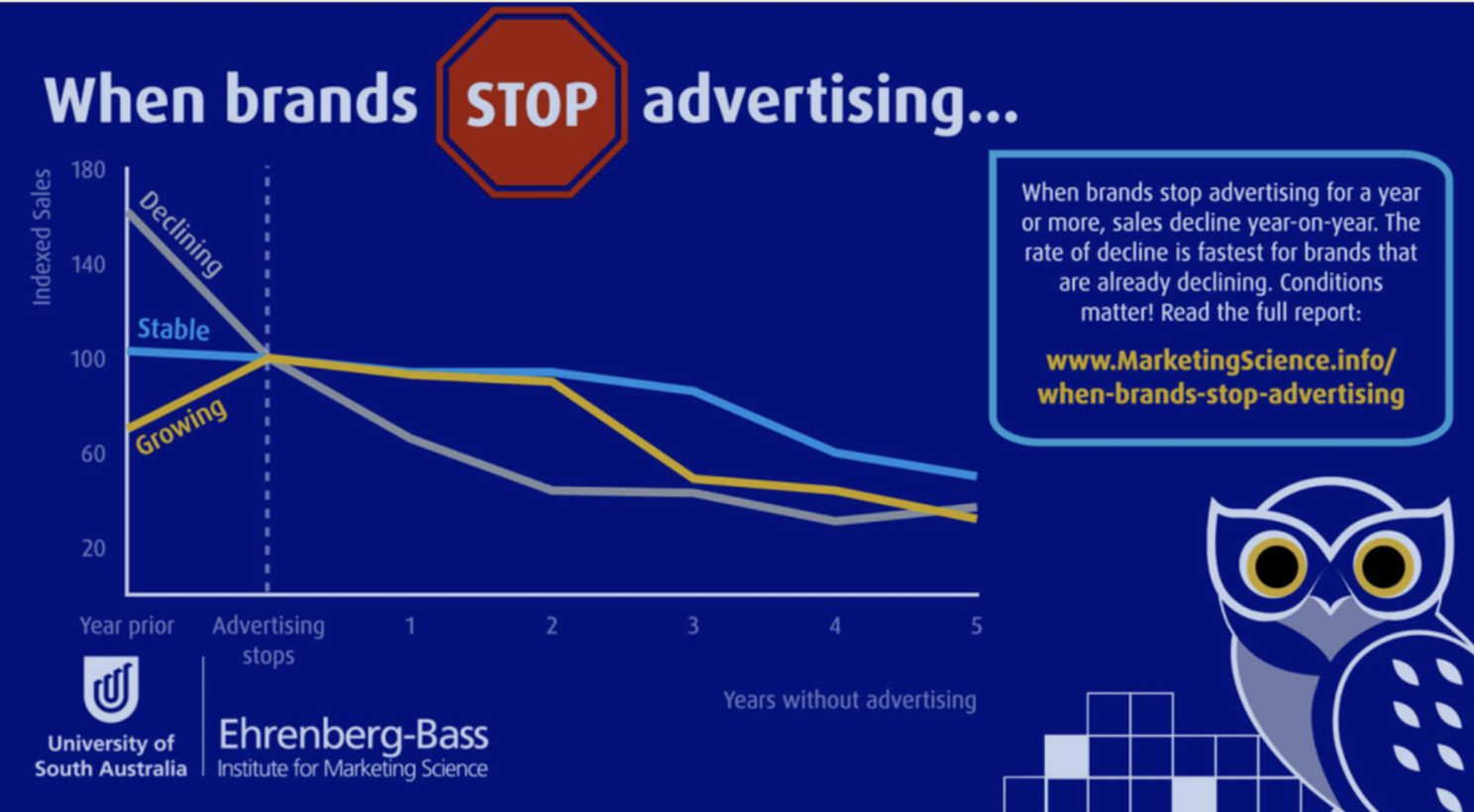

An article by Nicole Hartnett and friends explores the sales decline after brands stop mass advertising (go dark). What happens is an average 16% sales decline in the first year, 25% in the second year, and 58% in the fifth year.

Growing brands and larger brands can stave off this decline for longer, but the rate of decline is fastest for brands that are already declining. Apple was a declining brand but also a large one within their category at the time. So, we could say that without “Think Different” active from Q4 of ‘97 to Q3 of ‘98, it would be reasonable to expect a few percentage points of decline in sales.

Seems that if you’re a large or medium-large stable or growing brand, then you’ll only experience minimal declines in sales over a 2-year period on average. This is obviously information the advertising industry doesn’t want you to know. Then again, a few percentage points can be a large amount of money. The following is what Apple’s revenue looked like when the campaign was running almost exclusively. Note: The advertising budget was $90 million dollars ($0.09bn) for that year, meaning they didn’t need much incremental effect for the campaign to be considered a net positive investment.

So, was Apple’s “Think Different” campaign effective?

As we know from Part 3, thinking that advertising campaigns can have a significant and prolonged commercial effect is a weak starting point. This is especially true if those ads don’t show a positive short-term impact. Memories decay over time, so while you might be able to successfully argue brand campaigns’ long-term effects, it’s not like they lead to sudden massive spikes in revenue many years down the track.

Calculating an exact answer to whether “Think Different” was effective would require taking a much closer look. We would need to analyze multiple variables from a period of time that occurred 25 years ago and access sensitive data that isn’t publicly disclosed. This type of analysis would be complex and honestly, unfeasible.

That said, everything we’ve analyzed so far shows that the campaign wasn’t anywhere as impactful as many marketers would have you believe–especially for an ad touted as one of the best of all time. Effective in what way and for whom exactly?

But “Think Different” won lots of awards!

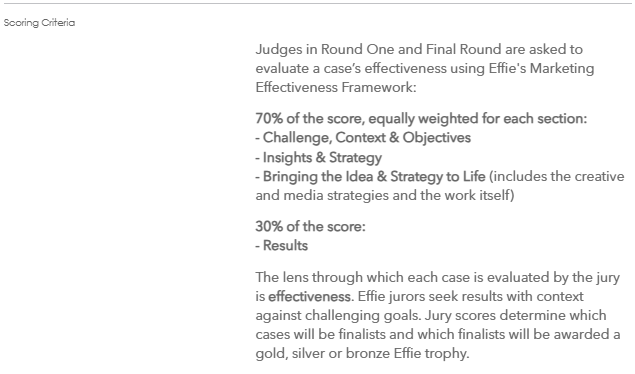

There’s an international marketing effectiveness non-profit called the Effie Awards. This particular Apple campaign has won many “Effies” over the years, but in one recent video, “Think Different” is presented as the main catalyst for their stock market turnaround.

A quick look at the Effies’ judging criteria shows over two-thirds of each entry’s score isn’t even dependent on campaign results. And those results are completely dependent on whatever objectives the submitting company wishes to use.

The judging guide goes on to say:

“Effie has no predetermined measurement of effectiveness… Effie is open to all forms of effectiveness – awareness, sales, behavior, etc. For some cases, it can be very important to achieve a change in awareness in the market and that may be very difficult to achieve. For other cases, the goal may be a change in sales. The determining factor is not what kind of goal the case had but….”

“Lionel Logue: ‘Oh, surely a prince’s brain knows what its mouth’s doing?’ King George VI: ‘You’re not well acquainted with royal princes, are you?’” – A King’s Speech

In other words, they judge effectiveness, but it’s up to you how you wish effectiveness to be measured.

Doug Garnet says this is nothing new, having exposed the holes in awards shows for years. Analysis of a “successful” Old Spice social media campaign in 2011 showed coupons were the main driver behind their success and not the social media campaign that was being credited for its success in the award submission. Convenient correlation is rife within the field of marketing, especially when it comes to brand.

I’m reminded of this timeless video by Sanjeev which sums up exactly why marketers avoid bottom line accountability:

Executives and brand effectiveness

Spending large chunks of money on marketing that doesn’t acquire more customers (market share) or gets people to spend more (market penetration) is a luxury very few marketing departments can afford to indulge in. And if you’re not achieving either, you aren’t actually growing the brand anyway.

Therefore, it’s illogical to argue commercial success relies on the ability to “build brand”, while simultaneously arguing against evaluating brand effectiveness based on commercial performance. Besides, what’s the point of “building brand” if it doesn’t translate to revenue?

And if brand marketers are going to use the time-lag get-out-of-jail-free card, they should at least be specific about the timeline and support their argument with data. Like Dale Harisson, who produced this model to help educate his B2B clients (note the “Ad Memory Half Life” reference under the “Assumptions” heading):

Getting a seat at the table

While this might be unorthodox for marketers to hear, senior executives (especially those outside the advertising industry bubble) don’t care about your campaigns unless you can show they have impacted business metrics. In other words, they don’t care about what 92% of marketers report on.

They might not say it to your face directly, but they’ll be thinking to themselves, “OK, some of our brand metrics moved upward, that’s great, but what does that mean for the bottom line? How will that help us reach our targets next quarter? And if not…what’s in it for me?”

How 99% of Marketing people talk about brand pic.twitter.com/vgr2PBiDFH

— John James (@adoseofjohn) November 10, 2023

Ross Sergeant summarizes this best: “We don’t need you to think about the beer, we need you to actually buy the beer. The share price, our salaries, and our bonuses go up and down based on how much beer we sold. So, one of the biggest problems we have in marketing is that, even in media, we go to very intelligent people (financial directors) and we try to throw them metrics that sound really great like, ‘We’ve increased the percentage of people who perceive this beer to be an Italian style beer from 67 to 82 percent!’. That’s great, but why didn’t they buy any more is the question.”

Long story short

“Think Different” looks like it’s had a subtle positive impact on Apple’s financial performance at best. And while it most likely paid for itself, It appears to have been far more successful within the world of advertising than it was for the company itself.

So, what started Apple’s enormous growth phase if it wasn’t an ad campaign? What triggered their meteoric rise in the years that followed? What put them on the path to becoming the world’s largest company?

To explain that, we’ll need to talk more about one key variable. Stay tuned for Part 5.3.

CFO and I auditing marketing in prep for 2024 pic.twitter.com/mDpma47JTd

— John James (@adoseofjohn) November 21, 2023

Cover image: IHX