“As our island of knowledge grows, so does the shore of our ignorance.” – John Wheeler

To understand how brand advertising works or doesn’t work, we must first understand how all advertising works. Inside the business community, there’s a common belief that advertising grows companies in a pretty straightforward manner. Something along the lines of:

“We’ve got a great product, a great brand, and a great team.

For our marketing to be successful, all we need to do is get the brand name out there.

The more we get our name out there, the more people will know who we are.

The more people know who we are, the more people will buy from us.

And the best way to get our name out there is by advertising.

So, all we have to do is create a great ad, put some budget behind it, and people will buy.

And once we’ve built up enough brand awareness, we’ll win. Simples!”

Unfortunately, almost everything about this is wrong. Which parts, exactly? Read on to find out.

Before you do though, make sure you’ve read Part 1 in which we define what a brand campaign is and Part 2 exploring the dichotomy between brand and performance by looking at the terms’ origins. For those of you that have read the previous two parts, you will have noticed that we didn’t define two other very important terms.

What is “advertising”?

Jenni Romaniuk of Ehrenberg-Bass defines advertising as “…a broad name for company-controlled creative activity (in any media) aimed at shaping buyer memories in the brand’s future favour.”

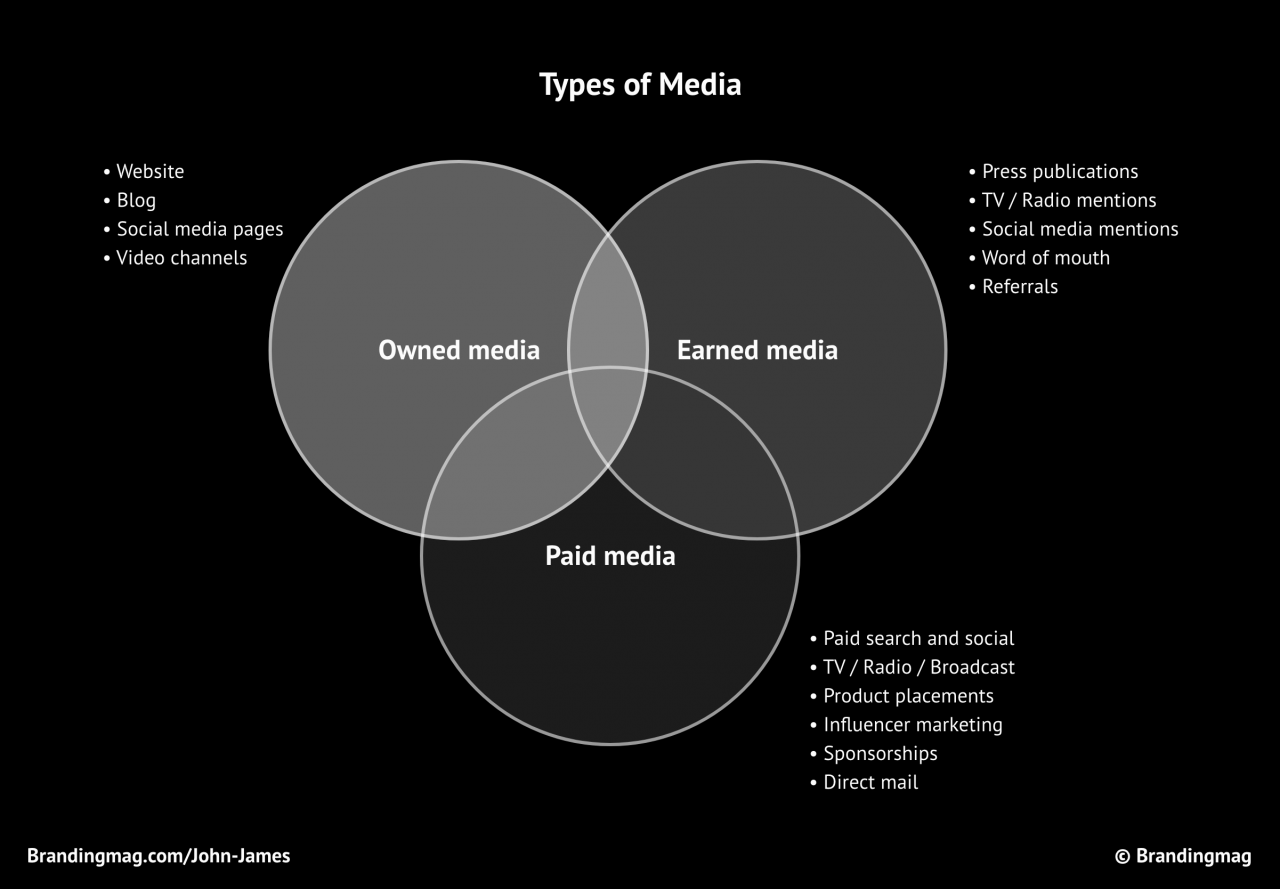

I prefer to break it down into the following three categories, mainly because each has different levels of trust, control, and cost associated with it. They’re also rarely sold together by the same vendor.

- Earned media–When other people mention you, the exposure has been earned. Publicity, social mentions, reviews, word of mouth, etc.

- Owned media–Channels you directly control like mailing lists, storefronts, social media pages, etc. Some break this down further into ‘shared media’ also.

- Paid media–What most people believe advertising to be. Channels where you pay to lease temporary access to someone else’s audience.

The problem with having most people equate advertising with paid media is that it reinforces a bias towards that which is paid (especially from those with agency backgrounds). Paid media dominates both discussions and company budgets because it costs the most, thereby attracting the most political attention and budget discretion. Paid media is also sold by advertising agencies, so companies relying on agencies tend to be overexposed, creating a self-reinforcing loop.

But today’s media landscape is very different from what it once was. Owned and shared media, especially, no longer have the same technical and financial barriers. But old habits die hard.

An easy way to illustrate this prejudice is by using a simple analogy. Is it better to own a home or rent? Every executive I’ve asked says, “Own”. “So, why are you allocating the bulk of your marketing budget to renting,” I ask? “Why temporarily lease access to someone else’s audience (paid media) instead of building yours (owned/shared)?” There’s usually an awkward pause as the point sinks in and they realize the error of their ways.

What is a brand?

It’s a simple question, but brand is an intangible construct so it’s difficult to explain in simple terms. Most will reference various proxies instead of brand itself. I even asked folk on LinkedIn this question twice on separate occasions. The answers were extremely varied, from “a brand is a business identity, a uniform for a business that allows customers to identify the business products; through logos, colours, pictures” to “the ability to charge a premium price designed to generate higher profit margins than your competitors”.

One person went way back, stating: “Expanding on a “burned mark on a side of livestock” roots of modern interpretation and meaning of the word ‘brand’. Given that it’s burned means that – it’s almost/virtually indelible, permanent, asserting ownership/belonging, conformity through look and feel, marking territory, clearly separating itself from others.”

The correct answer, in my opinion, is in fact very simple…

“Humans might be made from stardust, but brands are made by memories.” – Jenni Romaniuk

If a brand is just a collection of memories, then logically, we can conclude memories are formed via every interaction with a company (aka brand touchpoints). These go well beyond advertising to include:

- Customer service calls

- Salespeople

- Emails

- Estimates/purchase orders/invoices/bills

- Events

- Publicity

- Company announcements

- Media mentions

- Product purchase and usage

- Word of mouth

- What competitors say about a brand

- Signage, storefronts, and in-store experiences

- Packaging

- Sponsorships and affiliations

- Spokespeople and ambassadors.

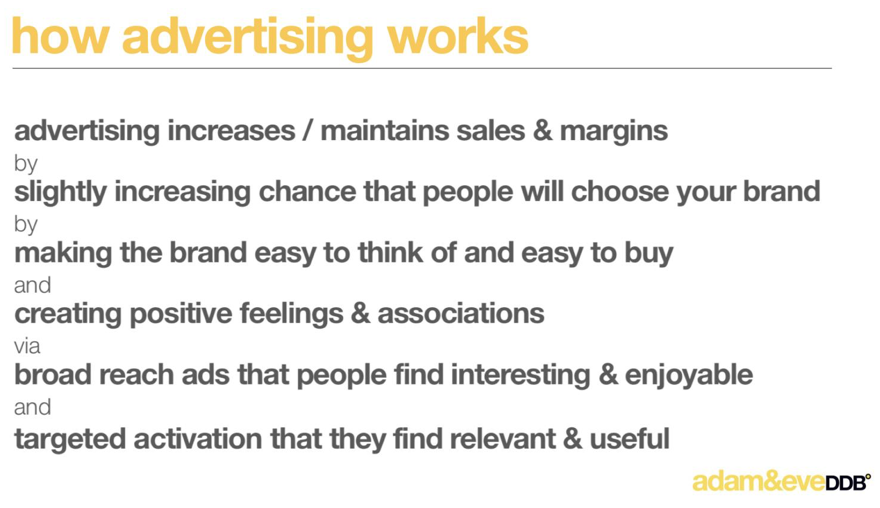

In fact, one could argue advertising has the weakest brand impact of them all–something everyone working in advertising will vehemently argue against (while simultaneously admitting in private that it’s true). Which is why I was surprised to see this pretty honest explanation of how advertising works from an agency in the UK:

My definition of “brand”

My personal definition of brand comprises three words: memory real estate. A collection of human memories in-market. Memories that vary from person to person, are imperfect, and degrade over time.

No matter what definition you use, if you’re not talking about human memories, you’re referring to some form of proxy for a brand. It’s as simple as that. For practical purposes, Ethan Decker helps delineate between two major categories of brand work you’ll commonly encounter in the video below.

How advertising works

There’s an underrated article penned by brand and advertising scientist, Jenni Romaniuk. It’s one of the most accurate and concise explanations of how advertising works. The article is a bit short though, so here’s an extended explanation that fills in the holes and expands on her points.

“Many people (amateurs usually) think exposure translates into profitability.” – @michaelcomeau

Jenni starts by saying we should ask the better question, “Why doesn’t advertising work more often?” According to her, advertising must satisfy three requirements for it to work:

- Reach

- Brand

- Be easy to find and buy

There’s a lot of nuance to each though, and that’s where everyone goes wrong.

Advertising must “reach”

This means the advertising must reach a person, a real human with blood and DNA. Not a bot. Not someone ignoring the TV while scanning TikTok. Not someone who no longer lives at that address or uses that email account. Not someone scrolling through their phone so fast they don’t see your ad.

This all sounds logical and common sense, of course, but here’s where it gets complex. Pretend you bought a Superbowl ad. How many of those 100 million viewers watched every single ad during every break from start to finish? Where was your ad in that session? How many people paid attention only to our ad? These are hard questions to answer, especially at the beginning of the planning process when predictions are all you have.

What about your viral video on TikTok? The one where you scared your cat with a cucumber and ended up getting over 3 million views. How many people saw that? Was a large chunk made up of the fake profiles social media platforms use to pump up their metrics? How many of the human viewers were inside your target market? Again, difficult to answer.

So this first requirement, reach, is as critical to the success of your advertising as it is problematic. Critical in the sense that ads can’t affect you if you haven’t been exposed to them. Problematic in the dense that determining just how many humans your ad can reach or has reached, is full of traps, waste, and inaccuracy. It’s a huge problem very few people talk about, because the answer is nuanced and complex.

Oils ain’t oils, and reach ain’t reach

Not all reach is equal. You need a very deep understanding of each medium and channel to determine actual reach. Knowledge throughout the entire advertising supply chain from creative encoding to transmission, decoding, device, viewport or viewing experience, all the way through to whether or not it enters a human brain.

The more separated you are from all these layers, the lower your technical knowledge and higher the chances you’ll have no idea. Most marketers are like this, so what do you do? You lean on the judgment of others.

As Eric Weinstein said in a podcast with Lex Fridman, “The human animal always wants to get around something like objective measurement. Because if you can get around objective measurement, you can tell a story. And if the story you tell is told to someone who knows less than you do, you can use that as the basis to transfer money from that person to you.”

Information asymmetry

Blindly trusting your agency report or the “reach” column of your digital advertising platform won’t give you an actual measurement of reach. But it will provide you with an estimate.

It probably won’t surprise you that a lot of advertising is bought by people who don’t actually know what they’re buying. There’s no perfect solution to this problem because there are too many channels to be familiar with nowadays.

While some waste is inevitable, decision-makers are led astray by people further down the supply chain that are incentivized to paint a rosier picture of reality. But a more subtle problem often left misunderstood is this waste is both disproportional and dynamic rather than proportional and fixed.

Details matter

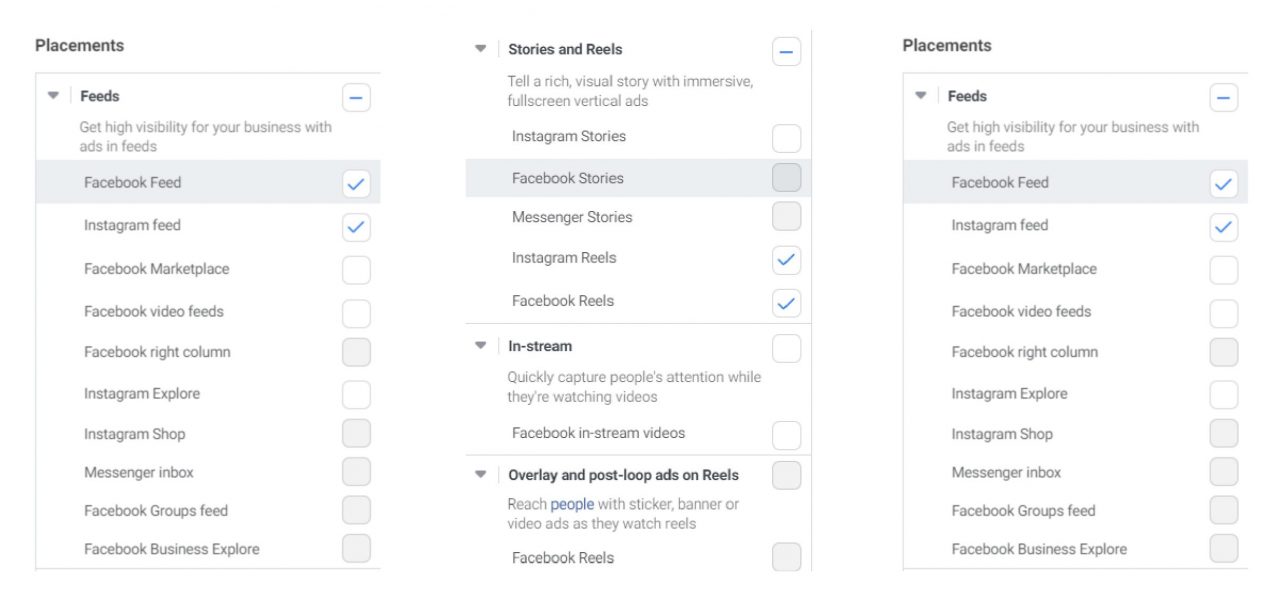

A lot of skill and domain knowledge is needed to be able to identify good channels from bad ones. The same goes for good and bad buys within the channel itself. When executing a Facebook campaign, for example, you must choose from over 8 categories containing several different “placements”.

Some of these offer far better human reach than others, but all will be ticked by default unless the operator manually intervenes. Dark user interface patterns are purposely designed to push a novice operator in the completely wrong direction–maximizing spend and the sale of junk inventory.

Most companies find all of this far too complex to do in-house, so they outsource the execution to a vendor. This vendor is typically an agency who, in turn, outsources the work to a media planner, who outsources it again to an employee or agency supplier (overseas operation) or worse, the publisher/broadcaster themselves! Error and conflicts of interest are amplified at each stage of this process.

Low quality media buys will command far lower levels of human attention and, therefore, far lower reach–but reporting will say otherwise. So, unless you have safeguards in place, you’re often dealing with poor quality media buys from the very start and you don’t even know it.

Counterintuitive and dynamic

Did you know buying TV spots between really popular prime-time shows commands some of the lowest human attention, even though they’re overpriced because “viewer estimates” are high and every client wants them?

Did you know Instagram and Facebook are now giving more default reach to Reels as opposed to other types of posts, so they can compete with the threat of TikTok?

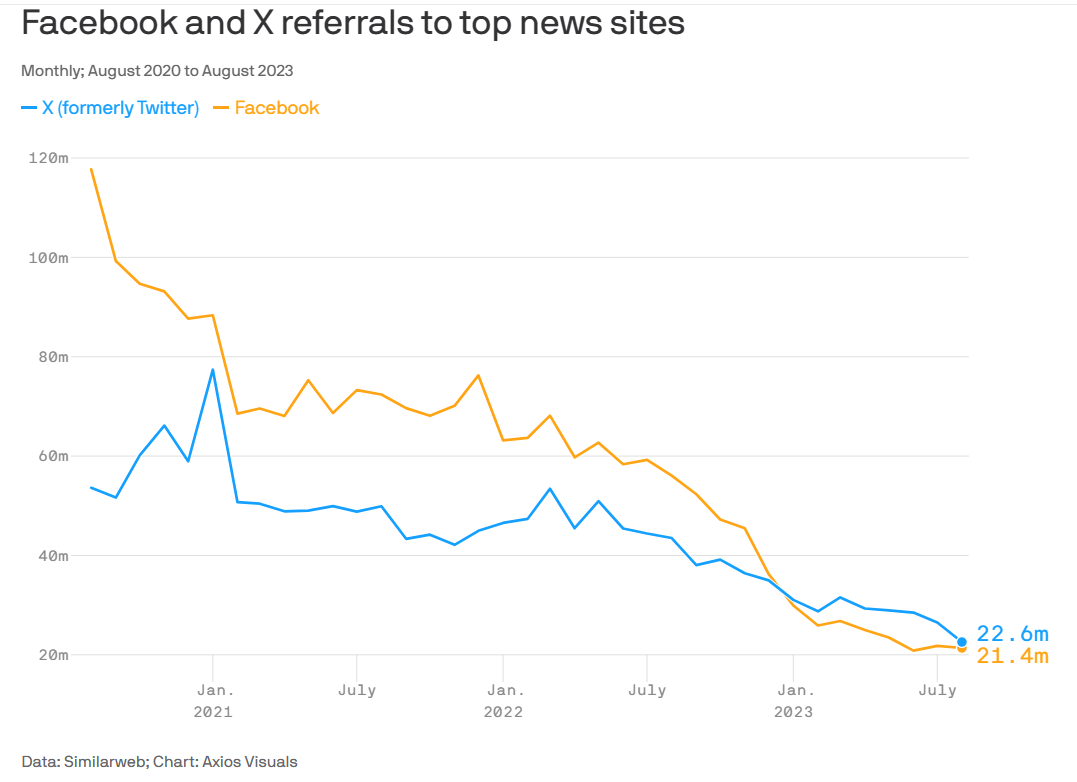

Did you know that over the past few months or years, there’s been a dramatic drop in reach for any social post that contains links?

Did you know that 20-60% of the Google search terms purchased now are not seen (“other search terms”)? That means 50% of your expenditure is going into a black box. It wasn’t too long ago that we had 100% transparency.

These fluctuations aren’t gradual either. Digital media can change yields instantly. A recent court case revealed that, in order to hit financial targets, staff manually made changes that affected all campaigns without clients’ knowledge.

The point is that reach is dynamic because media is dynamic.

Junk and fraud

The biggest waste of marketing budgets is the sale of this “junk inventory” (advertising media that commands low or non-existent human attention). This is because it’s something that only a highly trained media auditor or operator can detect. And when’s the last time you interacted with either of those people?

Digital media buys especially require a high degree of technical expertise if you want to exclude junk and ensure quality. The problem with digital inventory is that the waste is often algorithmic and disproportionate to expenditure. There’s no fixed wastage percentage like there is with offline media, which means doubling your budget on some channels without the right controls can more than double your wastage.

Junk inventory is similar to the way junk bonds or stocks are sold in finance to willing participants who don’t know better. Publishers, broadcasters, and platforms have no problem offloading their highest quality advertising inventory, but leftovers and fake media are harder sell. So, they relabel or package these into deals to agencies who on-sell it to clients. Agencies get their commissions and clients don’t notice because they still get advertising that looks good on paper. Lots of impressive volume metrics like engagement, reach, impressions, visits, clicks–even awareness. All of them proxy metrics for the one thing you should care about: verified human reach.

Without proper independent oversight on your media buys, it goes a little bit like this…

How advertising media planning works at agencies pic.twitter.com/oSsAhklGAI

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 4, 2023

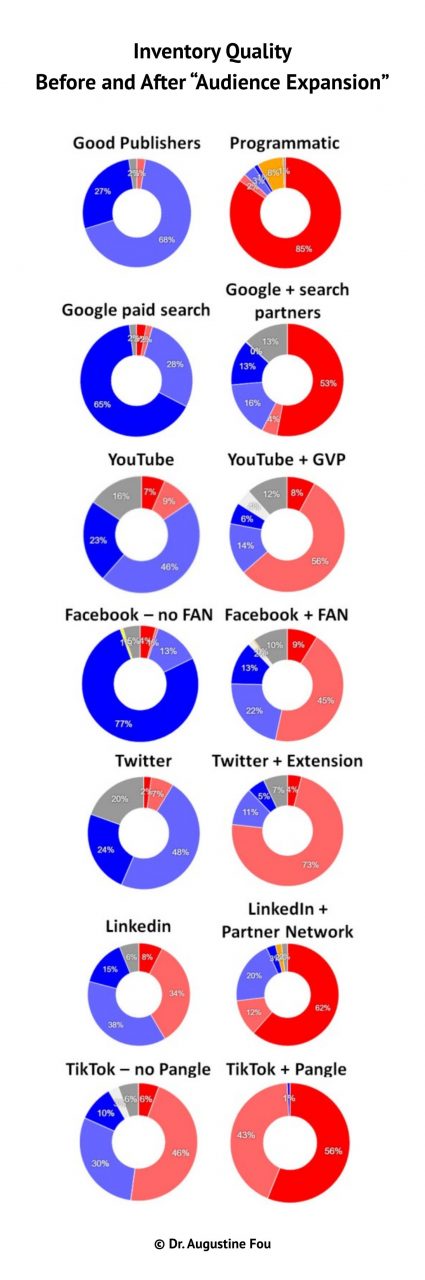

Dr. Augustine Fou recently studied various “audience expansion” features using his fraud detection technology. The left column shows the inventory breakdown before these “expansion” settings are activated. Blue denotes quality inventory and red shows low quality, bot, or fraudulent inventory. With various forms of “audience expansion” settings activated, the right column shows just how much junk inventory will be inserted into your campaign.

In the case of TikTok, maximum effectiveness can drop 40x to just 1% with the selection of a single setting. And this is just one small tick box–one setting out of hundreds that may be available to your operator. So, contrary to popular perception, details matter when it comes to effectiveness!

Tech subterfuge

I can’t mention names, but here’s something even worse: One of the largest advertising agencies in the world touts a proprietary piece of AI-powered media optimization software that they sell to clients for an additional fee. This program “optimizes” campaigns by buying junk inventory on the cheap before inflating the price by up to 50%. It then inserts this media into the client’s campaign. The client believes they’re leveraging AI media-buying tech that enhances the quality of their advertising campaign in real time, but they lost 50% of their budget autonomously without knowing it. You would think a “reputable” company wouldn’t do that to them. Dr. Augustine Fou’s latest research resulted in similar findings.

The sale of junk advertising inventory is by far the largest and best hidden problem plaguing marketing effectiveness today because it turns reach into “reach”, culminating in farcical scenarios that are pretty close to this:

When you buy digital ads with a reach objective pic.twitter.com/jDTAEJ2HIW

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 5, 2023

Vanity over sanity

The reason all of this flies under the radar is also because no one cares. The optics are still favorable. Reporting a higher figure to superiors sounds more impressive. Don’t believe me? Here’s a test.

Pretend you’re the boss, and you want to know how a campaign went. You ask your marketer and this is what they say: “The campaign was a huge success! It reached 300k people, got 5.5k post engagements, and 2k visitors to the website. And we generated $1M in sales during the same period. Our agency is entering us for an award!”

Compare that to marketer #2 that comes and says: “Facebook ad manager reports that we reached 300k people, 99.5% of them for under 3 seconds and 67% of them being outside our target market. We had a lot of spam comments and only a handful that sounded genuine. Lots of clicks, but 90% of that was low quality bot traffic because those website visitors bounced (left within 3 seconds). And when we checked via offline primary research and qualitative interviews to balance our digital attribution over-reliance, only two customers mentioned they had seen our ads prior to purchase. So far, it looks like it was a waste of money.”

Honestly now, which story would you prefer to hear? Don’t feel bad; according to Ross Sergeant, even the largest brands in the world are affected by this:

Advertising must brand

According to Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, “The original meaning of ‘brand’ was ‘burning’, which is of Germanic origin and related to the German word ‘Brand’, which also means ‘to burn’. The verb sense ‘mark permanently with a hot iron’ dates from late Middle English, giving rise to the noun sense ‘a mark of ownership made by branding’ in the mid 17th century. This then developed into the modern sense of the word as a type of product or service made or offered by a particular company under a particular name in the early 19th century.”

I spent some time on a cattle ranch in outback Australia when I was younger. I’ll never forget the smell in the air when the branding iron started to sear into the skin of the cow. Much like how this moment is seared into my brain, advertising has to do something similar in order for it to work. It needs to sear into the mind of the person you’re targeting. Not only does a human need to be exposed (reach), your creative needs to penetrate their perception and anchor to the right part of their memory–to the product category your company is associated with.

It’s even better if that advertising can do this around a particular buying context. Some people call these buying contexts product use cases, category entry points (CEP), or jobs to be done (JTBD). It doesn’t really matter which term you use. The point is you need more than just awareness. They need to associate your brand with the thing that you’re selling. It sounds obvious, but it’s possible for people to be aware of your name without associating it with the actual things you do! Here’s an example from one of the top ten advertisers in Australia:

Salience vs. awareness

Here’s another example everyone can relate to. Think of all the time you’ve spent socializing with friends. Your friends might know your name but fail to understand exactly what you do professionally. It often takes multiple meetings and longer, in-depth discussions with the same person before they truly understand what you do. Before that, they may know what you call yourself, but they won’t refer to work unless they can place your skills inside a familiar professional category.

I personally suffer from this problem. Some friends think I help companies with their advertising. Others think I do something with Google. Others think I write LinkedIn posts and produce Twitter memes all day. One client introduced me to others as a brand strategist (because that’s exactly what I did for them), while days later in a different client meeting where I was helping them with marketing operations, the client said out loud that my weakness was I didn’t know much about brand.

When speaking with Jonathan Rolley, he brought up a good example concerning Dominos. It’s not sufficient that we know who Dominos is. We need to know Dominos does pizza takeout and delivery. When I’m hungry and want dinner (buying context)–and I don’t want to dine in, make my own food, or go to a friend’s place (sub-category buying context)–but I want to pick up something quick or have it delivered to my door (sub-sub-category buying context), I will tap into a memory within my brain that has associated Dominos with that context and make a purchase decision.

Awareness is correlated to sales, but it doesn’t directly lead to more sales. Contrary to popular perception, brand awareness probably shouldn’t be the primary goal of your brand advertising, especially if you want it to generate revenue.

The passage of time heals all ills, except…

Time might heal animosity between people, but it does the opposite to your brand. Sometimes, it’s months or years before I see friends or colleagues. During this time, we’ve often both forgotten what each other does. That initial memory degraded over time.

To prevent this, we either need multiple visits in reasonably quick succession and/or sufficiently deep interactions to keep the memory reinforced. Just like that moment on LinkedIn or Twitter when someone changes their profile pic, and it takes you a while to recognize who it is, even though the rest of their profile is exactly the same.

Creative creative

For an advertisement to brand, we need quality creative (from a customer’s perspective) that helps burn the right memories into people’s brains. This doesn’t mean industry-award-winning, funny, smart, well-produced, or perfectly aligned artwork with a logo of a specific size. The creative you use to achieve this varies.

In a crowded marketplace, brand science has discovered it helps to stand out from the crowd (be distinctive) for your branding efforts to work best. Studies have been done to show how distinctive ads are more likely to be effective. It should come as no surprise that creating ads that look and sound like other ads doesn’t help you stand out from the crowd.

One of the big paradoxes of advertising is that the safer, more sensible, more logical, and the more it looks like an ad, the more it will be similar to what everyone else is doing. Unfortunately, these ads are also more likely to be approved by the client even though they won’t be as effective.

Scheduling, frequency, and cycles

The details of your media scheduling are also important because there’s a tendency for media agencies to schedule in bursts or periodic campaigns. If you read Part 2 of this series, you will have realized campaigns are an industry construct, which unfortunately works against your advertising’s effectiveness.

This is because campaigns often don’t account for buying cycles and memory decay. For advertising to “brand”, it needs to stay in human memory up until the point that person enters a buying situation. Otherwise, it’s all for nought.

Human memories are in a constant state of decay. It’s not sufficient to create a memory in someone’s head (awareness) and associate it with a buying context, you also need to maintain, refresh, and reinforce that memory over time to ensure it stays salient.

This means that a short burst of advertising followed by periods of nothing (or far less) is probably an unwise approach. Nor should you constantly make major changes to the way you advertise. In other words, you should be doing the opposite of what nearly every marketing department does by default (i.e., think in campaigns, constantly launch new creative, rebrand, change messaging, change CMOs and agencies regularly, etc.).

For each product type, you must account for the buying cycles of its market relative to the number of people you’re trying to reach. This may require consistent advertising that lasts for days, weeks, months, years, or decades! I once ran Google search ads for a client that I didn’t even know were effective until I analyzed a 24-month period.

Some people clicked on an ad, signed up for the newsletter, and didn’t buy anything for years before coming out of the woodwork to buy a million-dollar painting! Adjusting your advertising approach to cover the average sales cycle is critical. Byron Sharp explains how important accounting for advertising’s lag effect is in this short piece here.

The product must be easy to find and buy

Let’s assume your advertising has reached a human and latched on to their memory with your company’s name now associated with a buying context (sections 1 and 2 above). The next thing you need to do before it converts into a sale is ensure your offering is easy to find and buy.

This third point is never addressed by advertising agencies and frequently overlooked by internal teams, typically because no one is tasked to monitor breakdowns in the path to purchase. The work is not particularly glamorous. Not many political points to be gained and it spreads across multiple functions. So, while improving this area is basic customer experience hygiene, it’s a logistical and political minefield to navigate.

Simply put, the problem is that practical things can completely scuttle a sale. If the product isn’t available in that area or store (and a competing brand is), for example. Or if a prospective customer calls the phone number and it’s not answered promptly. Or if the person on the line is not sales trained and misses subtle cues. Or if someone browses the website and can’t find what they want. Or if the proposal takes too long to come back to the prospect. Whatever it is, very simple things can make the product difficult to find and buy. This can easily prevent sales, even if your advertising has satisfied points 1 and 2.

This third step is the practical stress test of all the upstream activity. It puts everything into a live context. Very minor practical barriers can easily derail millions of dollars of advertising expenditure. This is why savvy companies focus a lot on eliminating purchase friction, maintain their distribution hygiene, and religiously monitor all their brand contact points. The point of sale is marketing’s ultimate test–it’s the moment of truth, and customers can be brutally unforgiving. 35 seconds into this video, Jeff Bezos explains this very point:

In the same article mentioned earlier, Jenni Romaniuk summarizes her problem with advertising: “The vast majority of ad spend modeling doesn’t adjust for these factors [1, 2, and 3 above]. It’s no wonder then, overall, the story for advertising looks a bit murky…currently it’s like trying to judge employee performance just by how many hours they worked…and if marketers could stop claiming it is a good thing to spend large amounts of money on advertising that is not aimed at generating sales (short or long term) – that would help too!”

All of this will become very apparent in Part 5 of this brand campaigns series when we begin to analyze the famous Apple “Think Different” campaign. It reveals some massive externalities that made the campaign appear far more successful than it actually was.

Advertising works by persuading people to buy, right?

Ethan Decker busts the common myth that brand advertising campaigns shouldn’t sell, but do they? Ironically, advertising isn’t very good at doing the one thing everyone thinks it does: persuade people to buy.

“…we have different expectations for what advertising can and should do for them [new brands]. New brands have the novelty that they are new to the world and this may gain them some attention, but their lack of mental and physical availability is a major disadvantage.” – Byron Sharp, Marketing: Theory, Evidence, Practice

Contrary to popular belief, advertising is a weak force and not particularly good at generating sales, especially for less established brands and if not used in very specific ways. Advertising is far better at maintaining and protecting future sales of large established brands than it is at generating sales for new brands, which is why you see large brands advertising a lot. They do this not not only because it’s more effective, but also because they can. Budgets are generally less constrained and there’s less pressure for immediate returns.

And as we discussed in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, this makes it extremely dangerous for smaller brands to emulate the advertising activities of larger brands. Like a little brother blindly copying his older brother.

Byron Sharp goes on to say that “…[advertising] is actually particularly good at reinforcing existing loyalties (and memories) and it does this by reminding people of things they already know about. Advertising helps established brands stay in the market, just as much as it helps new products find customers.”

Big brands vs. small brands

Using advertising to form new memories for people unfamiliar with you and convincing them to buy is a much harder task. Yet this is what small-brand marketers attempt to do, creating unrealistic expectations for advertising from the very start. Malcolm agrees and explains how hard it is to do this, arguing small brands are better off investing in direct marketing instead:

Established brands typically use advertising for defense–simply refreshing memories and reactivating people who are already somewhat familiar with the brand. And the larger the brand, the more people there are familiar with it. This makes advertising both easier to execute and more effective, so large brands win twice. Meanwhile, small brands lose in multiple ways. This is why big-brand marketers often fail horribly when trying to work for a small brand or startup.

According to Byron Sharp (same book), “Advertising is comparatively weaker at building new memories, and rather poor at convincing people to form intentions to change their behavior. So it has a natural advantage in encouraging existing loyalties – encouraging people to continue doing what they already do. So, a very large role of advertising is to help prevent sales erosion; to prevent consumers forgetting about the brand and so buying it less often.”

One of the biggest mistakes I see all marketing folk make is copy a big-brand playbook for their much smaller brand, and then wonder why it didn’t work. Agency vendors are often very aware of this impending doom, but won’t give you a heads up because you’re paying them to ignore it.

As Marc Randolph (founder of Netflix) says above, challenger brands would be better suited to using a different approach, a completely different playbook agencies almost never recommend. Which brings us to the direct marketing/direct response style of advertising.

Brand ads don’t need a call-to-action?

Many people believe a brand campaign is superior to hard-selling, “direct response” ads–that brand ads shouldn’t have a clear call-to-action (CTA), explicit pricing, or overt sales persuasion messaging (see Part 1 for this discussion). There’s some truth to this because, as Byron Sharp wisely states, “….advertising largely works without forcing people to consider and change their opinions…this is why much advertising can get away with being very ‘soft sell’, with few or no claims of product superiority…”

According to Ethan, even getting them to think of you at all, should have some effect on sales.

But direct response advertising generates sales, right?

What about those infomercials you see on daytime TV or those product sales channels? Dollar Shave Club on Facebook, direct-to-consumer underwear brands and meat grills on daytime TV. They try to persuade you to buy over and over for 3-5 minutes at a time. Surely they generate sales?

Advertising’s effectiveness really depends on how you use it, the execution details (something many marketing folks are completely separated from). Skilled direct response professionals argue their form of advertising is very effective at generating sales, even for new products. After all, direct response advertising people are the most skilled at making sure their advertising translates directly into sales responses. It’s in the name.

I tend to believe this is true because the most skilled marketing professionals I’ve ever met all have a direct marketing/direct response background. At the same time, however, this doesn’t mean these people can escape the macro forces that constrain their ability to generate sales.

The people you’re targeting might not be in the market for your product right now. They might have just bought a competing product, or they might have already bought yours and don’t need a replacement just yet. They might be on holiday in an unfamiliar area. Another product might be running a discount for a short time, or the product category might just not be in vogue anymore.

“A lot of advertising is geared to persuasion rather than building mental availability. Persuasion is about assuming you’re in the room arguing your point. Whereas mental availability is about getting into the room. So that’s the big challenge – most organizations are failing to get into the room. But they’re spending all their money arguing as if they are already there.” – Jenni Romaniuk

Advertising can generate sales efficiently if you carefully target in-market buyers and use direct response tactics to convert them. But it can’t force you to buy something that you weren’t already going to buy and if you keep targeting too tight, you’ll also forgo the growth opportunity that comes from out-of-market buyers.

Maybe not sales, but brand advertising builds awareness, right?

Oftentimes, when you’re being sold the concept of brand campaigns, most people’s rationale hinges on the claim that these campaigns are good at building awareness. The assumption here being that more awareness = more sales. Some of this belief comes from the history of a famous model called AIDA, a model rife within marketing education and training associated with the advertising industry. But its use by brand campaign proponents is slightly ironic.

As Byron Sharp reminds us, “…AIDA (1898) was initially developed for training salespeople and was (unfortunately) transferred to try to explain how advertising works. This model said that advertising moved viewers through a number of sequential stages: from attention to interest to desire to action (AIDA). However advertising is very different from a salesperson’s interaction with a customer

Old models such as AIDA reflect the common notion that the purpose of advertising is to drive sales by telling us things we don’t know or changing our beliefs, such as convincing us that we should be buying a different brand from the ones we usually do…However advertising is mostly a weakly persuasive force. People don’t tend to pay it as much attention as marketers would like and consumers aren’t pushovers and they largely discount persuasive claims (they know advertising is a biased message trying to sell them something).”

Recent research also challenges the main assumptions brand campaign fans rely on from the AIDA model. In fact, researchers found that attention doesn’t come first but rather the affect > cognition > experience hierarchy was more dominant.

Many people also think the ‘A’ in AIDA stands for awareness, but that’s another story.

Brand advertising

In a recent interview, Matt Watkinson stated that you can make a lot of money by selling “combinations of two or more abstract nouns or verbs”. A lot of the misinterpretations about how advertising works comes from how it’s sold to clients. In the hyper competitive struggle to win clients, buzzwords abound and mistruths are quoted. The danger is that after years and years of lies and half-truths, fallacies can become so commonplace they actually become orthodox thinking.

So, what does this mean for advertising campaigns that aim to build a brand?

Dispelling brand advertising

The term “brand advertising” is now so widely used it’s become part of the general business lexicon. But we can use a combination of inversion and logic to challenge the validity of this term.

What company advertises without their brand? What company forgets to include their name, color, or some other distinguishing mark in its advertisements? This would make no sense. So, all advertising that features a brand is a form of brand advertising by default.

Technically, brand campaigns could be a salesperson ringing up a prospect and saying, “Hi, my name is John from XYZ company” or a Google search ad that has your brand name in the URL. Or a YouTube video that features your logo at the end. Or the bright orange colored packaging of your Veuve Clicquot Champagne bottle sitting on the shelf. All of these are technically forms of brand advertising because all feature the brand.

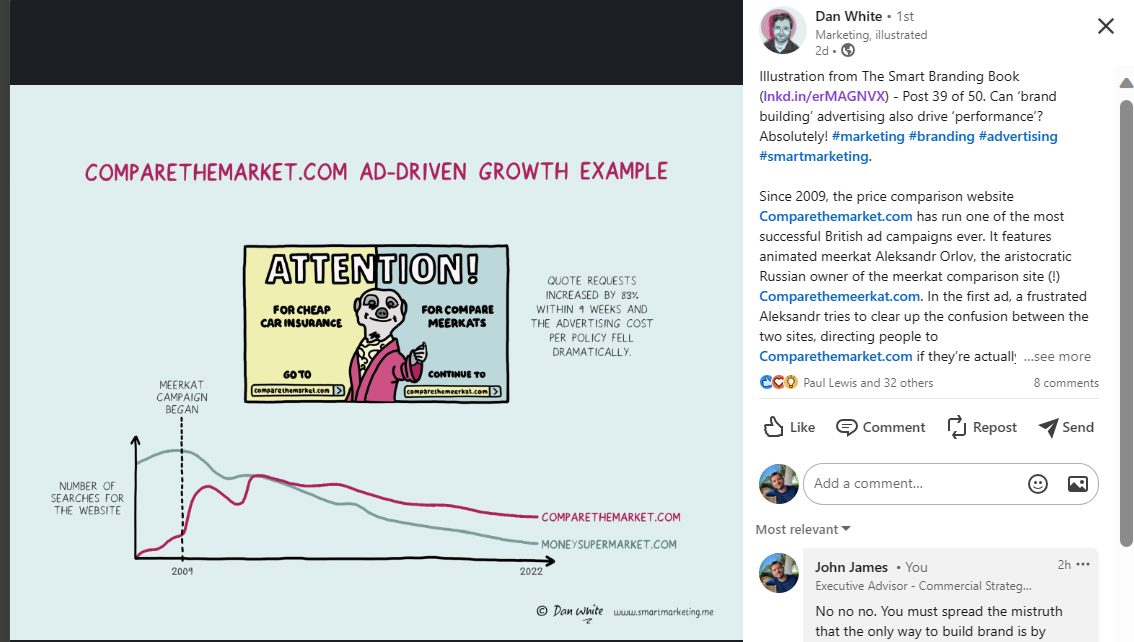

Others think brand campaigns shouldn’t be accountable to sales, but Everard Hunder disputes this:

And Byron Sharp agrees with him: “Marketers sometimes talk of ‘brand advertising’, contrasting it to advertising that aims to generate sales; ‘brand advertising’ they say, is to ‘build the brand, not generate sales’. This is confused thinking: the purpose of brand advertising is to affect buying behavior (i.e. to cause sales), and this is how it builds the brand.”

Some think brand advertising activities somehow sit in a throne room of their own–the exclusive domain of a particular person or role. But this is also a confusing way of thinking.

As Wiemer states, “It’s often angels on a pinhead when it comes to these semantics. Just show people what you have on offer and where they can get it. And don’t forget to make it 100% clear it is you who is doing the talking… The goal of advertising is to remind people your brand exists. So I see little difference between brand campaigns and ‘other’ forms – with the exception of promotions perhaps. We often overthink this stuff. Most normal regular people couldn’t give a toss. They might just vaguely remember seeing an ad with you in it at best, because recall often sits below 40%.”

Others think brand advertising must exclude the product you’re selling. Henry Innis disagrees: “The big challenge with brand campaigns is they can often forget the role that they’re meant to play – which is to build an association with a product or group of products. Too many brand campaigns are simply 30 second scripts without links to the product, which inhibits MROI and the broader link between great marketing and great business outcomes.”

Ethan Decker does a nice job of summarizing how brand advertising works here:

Brand advertising, marketing, and sales

But advertising isn’t all about sales, is it? What about all the other benefits? We can’t discount those, right?

According to Byron Sharp (same book), “Organizations advertise for a variety of reasons. Sometimes they advertise just to be seen to be doing something in order to appease distributors and motivate the sales force, or to show voters or employees that something is happening. So some advertising is mainly concerned with maintaining a good public image – it’s really a form of PR.”

By researching these campaigns and speaking to practitioners all around the world, it would be incorrect to conclude brand campaigns don’t have their place in a CMO’s arsenal. And while, technically speaking, they’re an industry construct pushed by vendors, many CMOs still buy them every single day.

Because I’m not an academic or a commentator but an active practitioner, what I’ve come to realize is that it doesn’t really matter if there’s no technical definition or scientific basis for something.

“What the eyes see and the ears hear, the mind believes.” – Morpheus, The Matrix

If enough people in the market believe it exists, it exists. If enough people buy into it, then there’s a market for it. In other words, what’s directionally true, based on a market’s perception of the truth, is the truth. Perceptions are reality.

Up next?

We’ve defined what a brand campaign is, described what brand and advertising are, and explored how advertising works. But what exactly does a brand campaign do that other campaigns cannot? Should we even use them?

Don’t miss out on the other articles in this series:

- Brand Campaigns, Part 1: What Exactly Are They?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 2: Where Did They Come From?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 4: Why and When Should You Use Them?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.1: Thinking Different about Apple’s “Think Different” Campaign

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.2: Debunking Apple’s “Greatest Ad of All Time”

Cover image: Viri