Every marketer is inspired by famous video commercials, especially early in their career. You know, those emotional, cinematic ads from brands we all know and love. Ads that tug at our heart strings, entertain us, make us laugh, cry, and empathize. Transit shelters adored with clever headlines that copywriters fawn over. Billboards playing with the sun’s shadow–content playfully oozing out their borders. These are the types of ads that get talked about, the types that win industry awards.

They stimulate discussion and spark debate on social media. Clients feel proud of the work they’ve commissioned. Internal teams become invigorated, brimming with renewed confidence. Agencies love selling them. Conferences love rewarding them. Publications write about them. Academics analyze them, and speakers feature them in presentations. Rival agencies look at them in admiration. And almost every marketer begins to emulate them.

And when you’re in this industry, it can seem as if everyone’s talking about these ads. Except for the fact that…they’re not.

And for many years I believed this award-winning work was the pinnacle of advertising success. Except for the fact that…it wasn’t.

“Everything is brand. Everything is sales.” – @jason_fox

What about the market? Those pesky customers we all rely on to support our company’s entire existence. What did they think? Did they end up buying because of these ads? And if so, how much? What was the commercial impact on revenue, profitability, market share, or company valuation?

Heck, what do brand campaigns even do in the first place?

Before you read on, make sure you read the previous three parts of this series where we define what a brand campaign is, explore the history of where they came from, and explain how advertising and branding really work.

Nine reasons why you should consider investing in brand campaigns

To brand campaign or not brand campaign–that is the question, right? Well, here are a few reasons to always keep in mind when you do:

1. Practicality

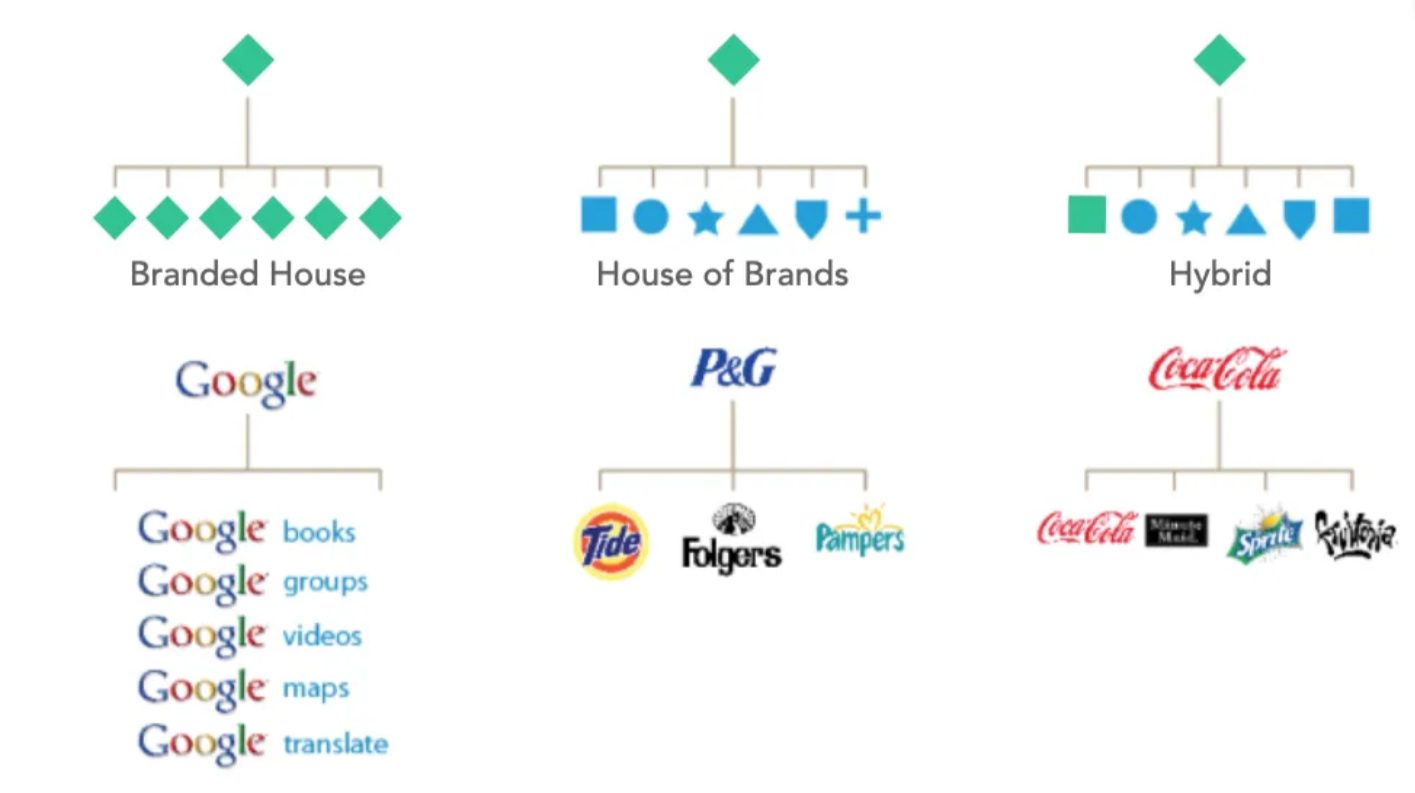

In Parts 2 and 3 of this series, we mentioned how large brands with similar products under one umbrella (a branded house) can get away with one brand campaign as long as the master brand is complementary.

2. Rectification

In rare cases, a problem at the brand level needs rectifying because it’s preventing a business goal from being achieved.

Imagine a firm with a fantastic product that’s selling like hot cakes–great pricing, distribution, and promotions. Then, it’s suddenly discovered that the company’s employees have been moonlighting as child slavers. It’s an extreme example, but an example nonetheless, of how branding can create negative halo effects over a firm’s entire performance.

More will be revealed in part 5, but one of the main reasons why Apple’s “Think Different” campaign was commissioned was to help assure their stakeholders the company would still be around. At the time, the company was facing bankruptcy and customers were worried they’d purchased products that would soon become obsolete. Such fear would cannibalize future sales at a time when the company could ill afford it. So, a brand campaign communicating a grand, long-term vision helped allay these fears.

3. Rebrands

While I estimate that 95% of brand refreshes/rebrands are politically motivated, they can sometimes be self-fulfilling. So, we’re including rebrands here with EXTREME caution.

Organizations can get stuck in a rut after a period of time, it’s true. They become complacent as everyone settles into the groove and accepts the status quo. Sometimes, what’s needed is a reset–a reset that usually comes via management changes, external shocks, or a new chief marketing officer. A reset can trigger a renewed appetite for transformation and realignment between functions, while simultaneously giving executives permission to move on, scrap ideas, and deviate from past decisions (which can lead to positive outcomes).

Marketers love rebrands because they involve nearly all departments and touch multiple levels within the company hierarchy. So, this type of project is not only lucrative politically, but it can also be a great way of aligning the organization on what it does, why it matters (or still matters), what it stands for, what it wants to look or sound like, etc. In dynamic environments, this is not a bad exercise to undertake frequently, but rebrands aren’t the only way!

Lacoste pursued a rebrand when a perception problem in the mid-2000s was hampering sales. The brand was sliding towards obscurity as their boomer-dad base started to age. The brand was becoming stale and natural attrition set in. Post-acquisition in 2012, new management set out to immediately turn that around. They introduced fresh product lines and new colors and pursued growth in new markets (women and children). Concept stores complemented this revamped look and feel together with a new advertising campaign titled “Unconventional Chic”. Warning: There are clear product shots galore in this “brand ad”. Sacre bleu!

According to The Moodie Davitt Report, “The rebranding follows the appointment of José Luis Duran as the CEO of Lacoste’s fashion and accessories partner Devanlay…his mission has been ‘to bring Lacoste into the modern world’, rejuvenating the brand to better meet the desires of its customers. In addition to modernizing the brand, Duran also aimed to expand the Lacoste clothing line, refresh the range and make it more feminine. To this aim, designer Felipe Oliveira Baptista – who has experience with brands such as Max Mara, Cerruti and Nike – was brought into the company.”

Over time via combined efforts across ALL the 4P’s of the marketing mix (price, product, distribution, and promotion), they successfully shed their daggy-dad vibes and began oozing fresh, gender-inclusive, French chic instead. Fun fact: In 1933, Rene Lacoste invented the modern polo shirt for tennis, pioneering petit pique cotton. He went on to invent the metal tennis racquet and the tennis ball machine, too.

That said…99% of the time, rebrands are a total waste of resources.

A majority of rebrands are unsuccessful because of the way they’re born. Typically, it’s a political, knee-jerk initiative championed by a marketing leader looking to put their stamp of authority on a firm. These faux rebrands are easy to spot with their wafer-thin or non-existent diagnosis and visual-aesthetics-only focus. And, of course, when the design work is done, there’s an expensive, flashy brand advertising campaign to boot!

Real strategy involves crafting a coherent set of steps that work in unison to cover the entire mix, not shouting from the rooftop about how you changed your living room drapes. I suppose there’s nothing wrong with this if that’s all the company wants, but then don’t be surprised when you, as the marketer of such events, don’t “get a seat at the table”.

“Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like. That’s not what we think design is. Design is how it works.” – Steve Jobs

Small companies should be particularly wary of rebrands as they tend to be used to cover up deeper issues or, even worse, as a form of marketing procrastination. And rebrands nearly always go too far. Instead of a simple refresh or tweak, the baby’s thrown out with the bathwater. A small renovation project suddenly becomes a complete rebuild with invoices and timelines to match. Sweeping changes are made, which discards a lot of residual commercial value. Not to mention it’s still not finished 6, 12, even 24 months later…

These overblown rebrands usually happen because someone has a personal agenda and wants to make a statement. They’re either bored, don’t know what to do, want to gain visibility, or just want to funnel money to a friend’s agency. Either way, rebrands are a great distraction and stall tactic, making them a favorite of new heads of marketing (see step 6 here for details).

Elena speaks the truth, even going on to compare it to a dog marking its territory on a tree. Just think about Twitter’s rebrand: Was there a strong business case or was it ego-driven? The opportunity cost of a full rebrand can be enormous. A wiser approach would be to iterate from an existing theme and let the brand evolve naturally over time alongside customer expectations. But let’s see what the science tells us. Here, we have Ethan Decker explaining why rebrands are “a dangerous and risky proposition” from a scientific point of view:

4. Positioning pivots

While nearly all rebrands should be red flags, sometimes firms legitimately need to change the way their brand is positioned, especially startups and firms operating inside new, fast, and evolving markets. It’s not unusual for these early-stage companies to start with one product offering in one category and then switch to another. In startup land, we call this a “pivot” and it usually coincides with some form of rebranding.

A scene in HBO’s Silicon Valley illustrates how this typically plays out. In this segment, a larger rival copies their whole business model and announces it on stage just before they’re due to pitch.

5. Creativity

Part of the allure of brand campaigns is the creative flexibility they provide to different people. They inadvertently give us permission to move away from the confines of the hard product sell. As we learned in Part 3, your goal with advertising should be to gain human attention and build memories. And you can do this in ways that don’t even mention the product, its price, or where it can be bought. Increased creative license can lead to better ideas and more out-of-the-box thinking which can, in turn, increase attention and effectiveness.

“Beware of the soul-sucking force of reasonableness.” – Chip & Dan Heath in The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact

But bureaucracy is the enemy. In larger firms rife with politics, approval committees emerge masquerading as risk mitigation and “good governance”. This ends up stifling effectiveness because they automatically regress advertising creative toward the mean of normality. Instead of benefiting from a creative branding moment, you’ll get best practice with a side of safe, bland, and boring creative that doesn’t cut through.

Committees are geared to critique, rather than to create. Don’t design by committee, you will end up with only ideas and no execution. pic.twitter.com/cUlZqwi0zK

— Alvin Foo (@alvinfoo) November 12, 2022

What’s lost is the creative power to stand out from the crowd and affect human memory, which–as you know from this series’ Part 3–is a critical requirement for the advertising to actually brand. For example, there’s nothing logical about this ad with only 10 seconds of product shots at the end, but gee does it brand:

Oh, dear. Did I just fall for the thing I warned you about at the beginning of this article? Yes and no. Read on…

Creative freedom doesn’t mean unbridled creative license. There must be some structure and strategic discipline. Finding this balance is critical; otherwise, your advertising can quickly resemble ideas brainstormed by an excited group of school children. And given the median age of agency employees these days, that’s actually a real possibility.

Regardless of what people say, if you want commercial returns from brand campaigns, you can’t just entertain, be funny, and win awards. Your campaigns need to reach, brand, connect to a product category, and be easy to find and buy.

“The problem is that advertising agencies…are now infested with people who regard advertising as an avant-garde art form. They have never sold anything in their lives. Their ambition is to win awards at the Cannes Festival. At best they are mere entertainers, and rather feeble ones at that.” – David Ogilvy in Confessions of an Advertising Man

Let’s go back to Ethan for a moment as he details the freeing nature of this shift–how this renewed creative freedom is often enjoyed and preferred by staff all around (both agency- and client-side). Agency vendors often come into their own in these environments, which motivates them to assign better staff who in turn produce better work. So, it’s a win-win.

This means that brand campaigns can inadvertently provide teams the creative license they need to successfully…brand!

6. Costly signaling

We’ve all tried faking it ‘til we make it, and it can work even with brands. Signaling can be used to your company’s advantage if you invest in higher status, more prominent and expensive media. This can give customers the impression that your brand is larger and more dominant than it is.

It’s exactly what Spotify did when entering the Australian market as a relatively unknown challenger brand. To compete with Pandora’s dominance, they spent big on an outdoor campaign in all major cities. This gave the impression that Spotify was a big, established global brand entering the local market even when they weren’t. Just listen to Charmaine Moldrich recall the full story:

In his book Alchemy, Rory Sutherland calls this costly signaling. We naturally assume small brands can’t afford to advertise in the same way big brands can. As a marketer, we can use these assumptions to our advantage–budget allowing, of course–just like Spotify. You can also use it defensively. Some brands invest in expensive advertising media just to signal dominance and discourage competition. “Think you can compete with us? Good luck. We’re big, powerful, and better than you. We own this area.”

Once again, we see that true brand advertising campaigns aren’t always about near-term sales and revenue returns.

“A Brand Campaign is basically an ad that is so ridiculously expensive to make that all it says is look we are doing so well we can afford to waste shareholder funds on this for no other reason than ‘because we can’. Brand advertising is basically market signaling. It’s calling out the competition. Can you compete with us? Can you compete with that! This is what market leadership looks like! Etc Anyone who thinks otherwise is missing the point.” – @excapite

7. Memory management

Large brands often have so much brand awareness already that they use advertising to simply maintain and refresh memories within their existing customer base. This is why their advertising doesn’t have to be a hard product sell. Everyone already knows who they are and what they do.

As we learned in Part 3, memories decay and associations are lost over time. Brand campaigns can be a good way to reawaken and strengthen latent memories. In fact, a lot of the advertising we see is aimed at memory maintenance. Their goal is to ensure that when potential customers enter a buying situation, they buy the brand that is most fresh (salient) in their minds. Advertising’s purpose is often just to say, “Hey, we’re still here. Remember us?” This is why big brands don’t always explicitly feature products in their ads–they’ve earned the right not to. Same reason why small brands fail when copying this playbook without having enough brand equity in the background to make it work.

8. Growth

This is the big one that many companies (especially in tech) struggle with. It’s also my specialty, so a longer answer is required.

Breaking the shackles

All companies can get stuck servicing existing customer segments in existing markets. It’s a safe place they know well that’s reinforced with each sale. But this naturally caps growth potential, and I’ll explain how.

Disproportionate growth often requires a high risk appetite and ballsy moves because the company is forced to venture outside its comfort zone into unfamiliar target markets. Growth requires being open to broader market opportunities, possibly at a higher cost and lower profit margin–which of course, no one (especially the CFO) likes.

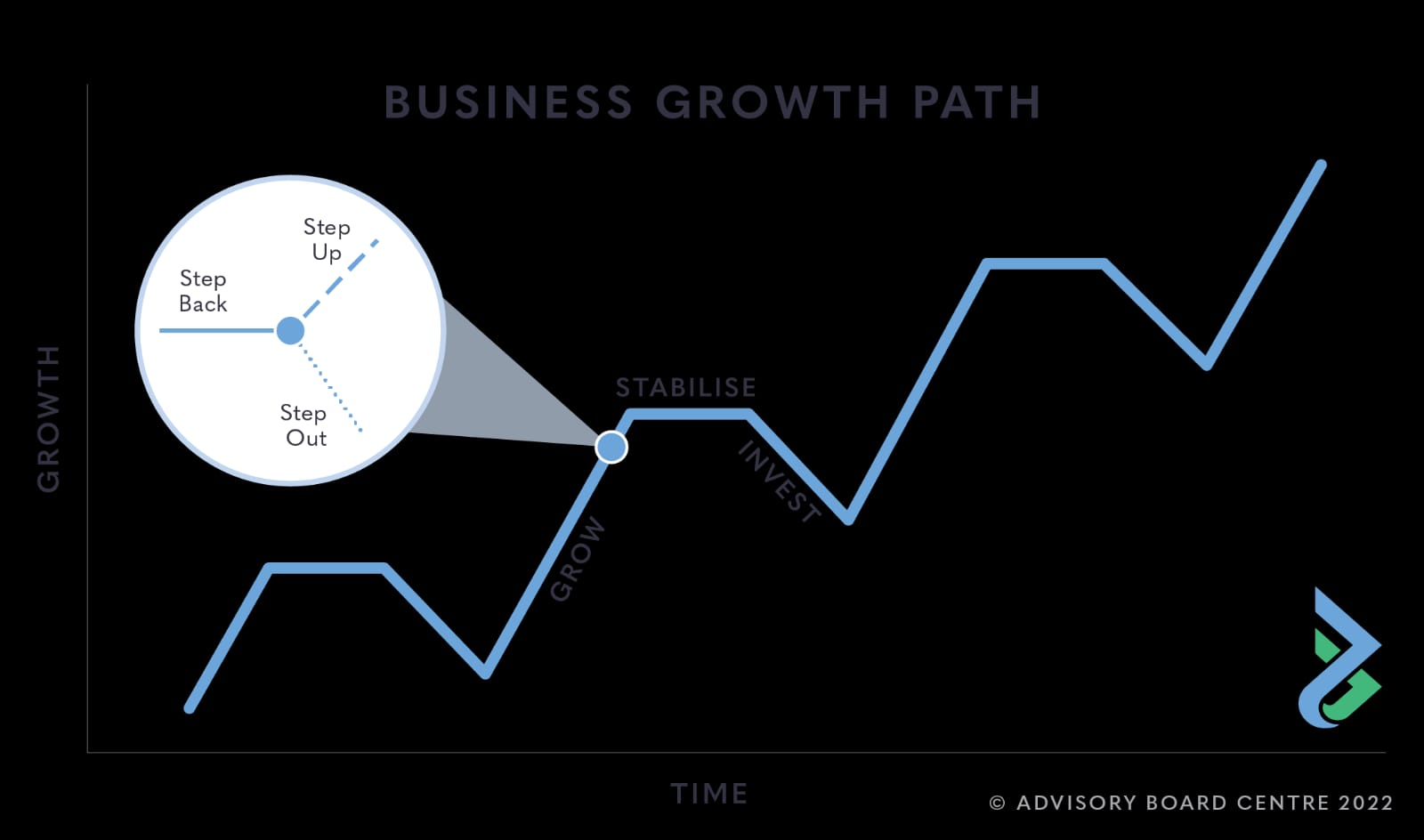

With the wrong mindset and culture, firms tend to avoid difficult but necessary trade-off decisions. This is one of the reasons companies tend to stall at certain growth breakpoints (~$1M, $5M, $10M, $50M, and $100M in revenue). Cue the “3 and 10 rule” and this illustration from the Advisory Board Centre:

Positioning

Legacy brands sometimes become too restrictive, so brand-level modifications are needed to accommodate these new customers. Just like a hip but niche artist. It’s “cool” and “chic” to be part of this underground movement in the early days, but all groups eventually hit a juncture where they’re forced to go more mainstream in order to pursue growth. Compare The Weeknd’s early works like “Or Nah” (NSFW) to his modern work. Very few of these older tracks are even allowed to be broadcast on radio, nor would they ever appeal to a large, mainstream audience.

Out-of-market opportunity

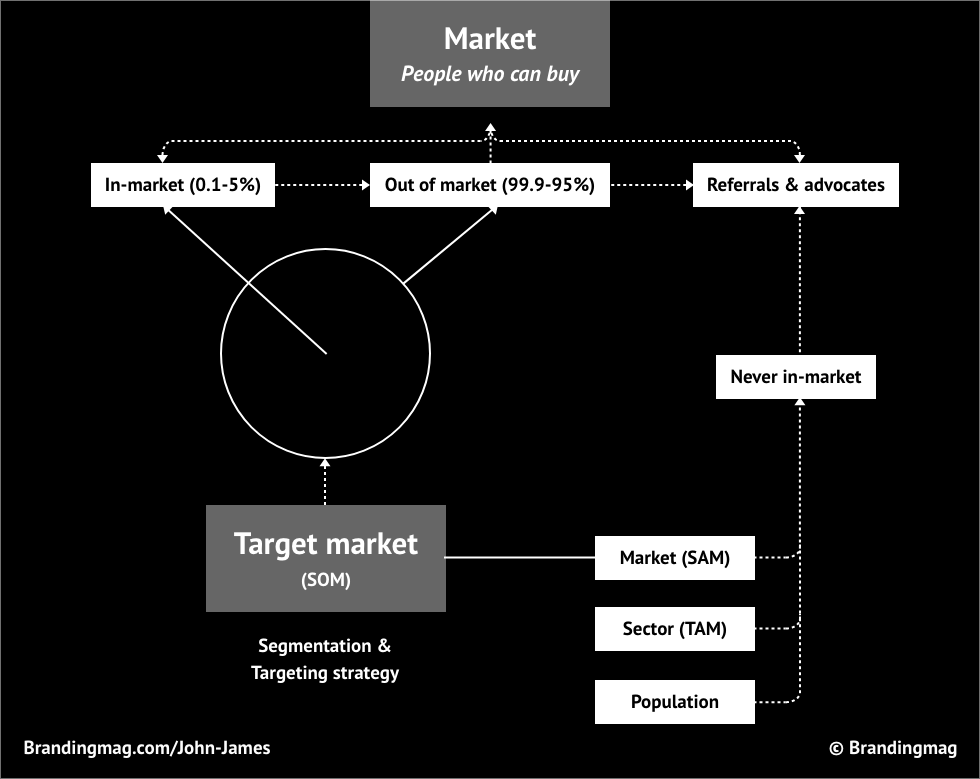

Companies can become too focused on exclusively targeting “heavy”, “in-market” buyers and ignoring the fact that “light-buyers” or even non-buyers provide the larger growth opportunity (19 to 20 times larger, for that matter). To grow and pursue this larger audience, companies need to advertise to people that are “out-of-market” (e.g., people that have already purchased within your category, but might purchase again in the future).

“A brand campaign is mostly focused on getting the attention of a broader audience that is not per se ‘in market’ (the other 95%) through stand-out creative content (paid or organic) with the goal of linking your brand to a certain need(s) (category entry points) but also making sure they are familiar with your distinctive brand assets, even if that is done unconsciously.” – @stefhamerlinck

Even if the brand campaign itself isn’t directly effective, it can help everyone appreciate the value of investing company funds in those who may never buy! In fact, one of advertising’s strengths is its ability to create a shared public understanding of your brand (i.e., fame).

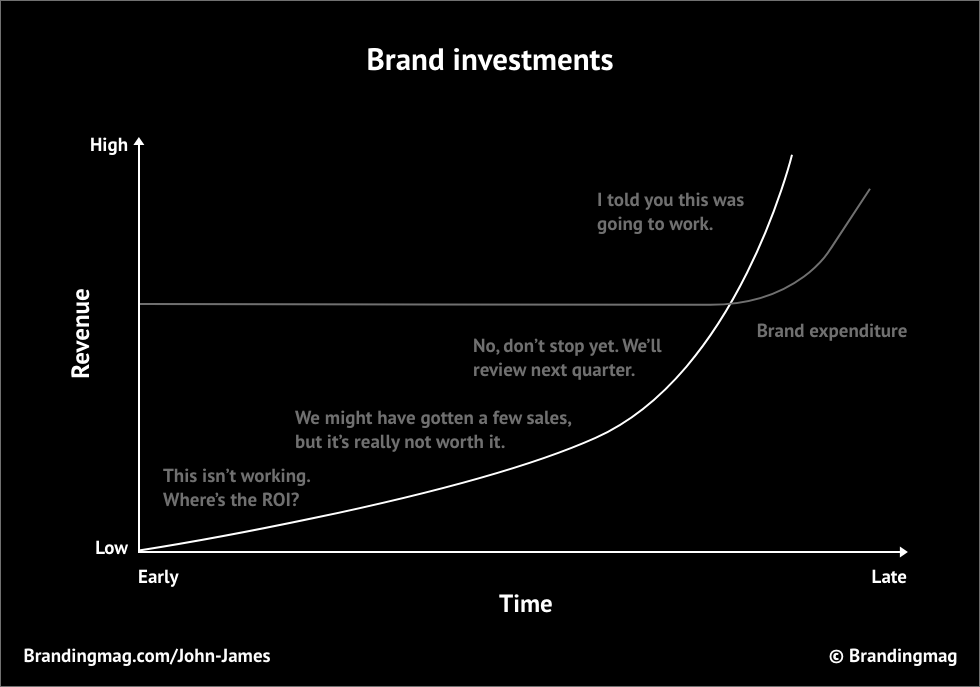

Non-linear measurement

If your firm’s full of data-driven bean-counters, then be prepared for their overreliance on the most obvious, immediate, primary effects of upstream action. They’ll look at marketing in a very linear, input-to-output manner and naturally isolate variables from the whole. But brand investments need people to embrace uncertainty, appreciate complex systems, understand how non-linear intangible growth assets work, and have (as mentioned) a higher risk appetite. This requires a massive shift in thinking.

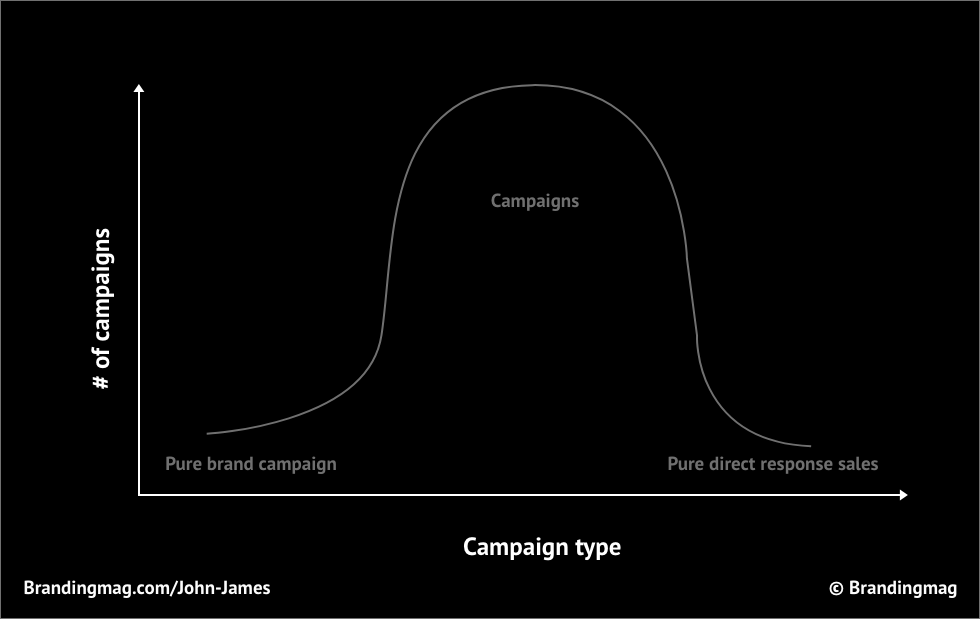

Channel yields

I’ve seen a lot of firms pursue brand campaigns after experiencing declining yields from their preferred, direct-response-style digital marketing investments. They had typically been using these channels to acquire customers at the lowest cost and in the easiest, most measurable ways. Money goes in; the most immediate, obvious metrics are measured; customers come out; and a crude customer acquisition cost or “return on investment” is calculated. Repeat ad infinitum. But with prices going up and yields going down, even “performance” channels themselves are now forced to explore the merits of brand advertising.

“A year after Meta began selling ads on Reels, the company is struggling to convince marketers that advertising on the TikTok rival can drive new business, ad executives say. Marketers typically view Meta’s properties as venues to run ads designed to persuade people to do something, like buy a product or download an app, whereas quick video ads that run on Reels are better to promote a brand.” – Sylvia Varnham O’Regan

Gumball machine marketing

As we just explored above, the marketing/growth function can easily start to be treated like a gumball machine. Jon Miller recently penned a piece exploring how this lazy thinking around digital media is unsuitable for an era with mature digital channels. Ironically enough, this article was written by an evangelist for a demand-generation software firm, Demandbase, that resells digital “performance” media wrapped up in a SaaS…

“Gumball” marketing eventually leads to diminishing returns as companies exhaust their pools of easy-to-reach customers. And privacy updates have skewered the accuracy of large data chunks that used to make this approach lucrative.

Heterogeneity

In an episode with Daniel McCarthy, he reveals how finance people often use an oil well analogy to explain how company growth works. To grow, companies need to expand past their closest, most efficient oil wells and venture out to explore the yields of other wells. Wells others might already be tapping into, where the yield can be lower, but the pool larger. All companies eventually need to venture into other wells (i.e., targeting lighter buyers, wider markets, and more expensive customers). This sometimes necessitates changes to the brand. If you’re interested, Roger Martin explains how homogenous market thinking can pose massive problems in this article here.

Brand campaigns and growth

Entertaining the new and unfamiliar creates uncertainty within organizations, which in turn, causes a conundrum. Businesses are far more comfortable staying in their lane than pursuing uncomfortable growth. There’s often no clear winner, so tradeoffs are inevitable and choices are hard.

Brand campaigns can be the first step where these firms concede a need to spend marketing budget in a way that:

- Services their entire total addressable market

- Embraces the notion of “waste” and secondary/tertiary effects

- Allows for the step-change opportunities that come from serendipity (luck surface area)

- Relaxes restrictive practices and allows for greater commercial creativity

- Helps everyone see the bigger picture.

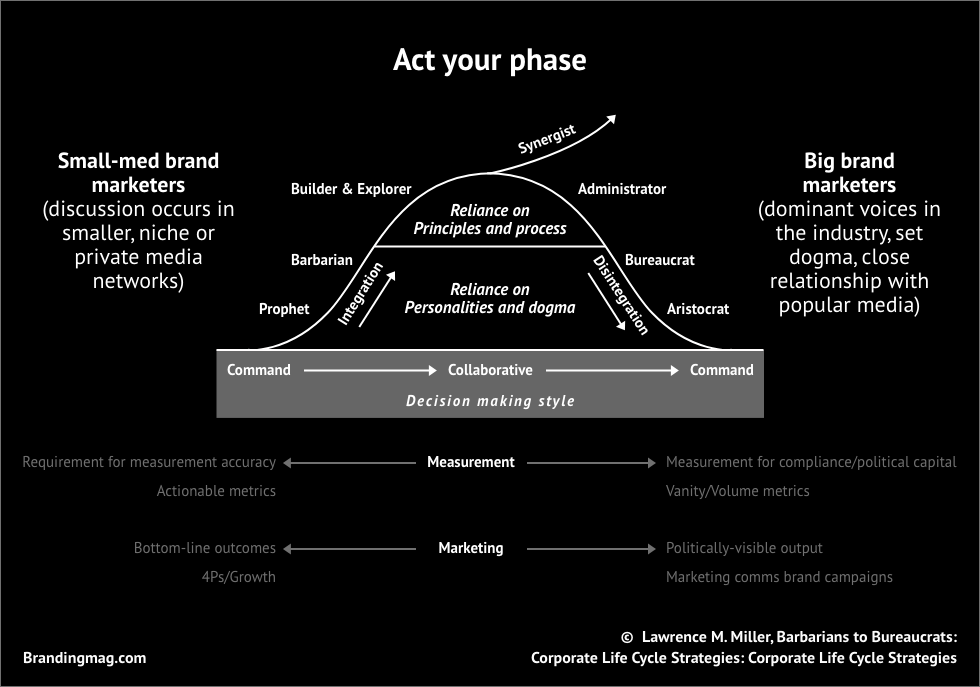

9. Delay and denial

Brand campaigns are sometimes a byproduct of the lifecycle stage a business is in. In his timeless book, Barbarians to Bureaucrats, Lawrence M. Miller explains how a whole raft of behavior stems from companies trying to be at a different point in their lifecycle than they are. And he’s right; a lot of brand initiatives are commissioned to entertain this gap.

The larger this gap, the more marketing will detach from bottom-line accountability. Just think about the times you were working in a role that benefited from a positive, sector-wide headwind. Now, compare that experience to the reverse. You’ll suddenly find the need to entertain viewpoints that are increasingly detached from reality. In these moments, executives want to maintain order, prevent panic, and avoid the glare of disgruntled investors. This is when brand campaigns really come into their own.

“When I told my old CEO we had a business model issue, his next hire was a brand girl to run brand campaigns. Their business model didn’t change one bit. I even proposed a new business model. The issue was, he was happy to ‘hold the CEO seat’ for the three years – tread water – and then retire. Lol.” – Anonymous CMO

A world-famous company valuation expert, Aswatch Damodaran, explains how fighting your place in the corporate lifecycle is perhaps the most dangerous thing companies can do.

Don’t choose brand campaigns for…

1. Short-term sales

This hopefully doesn’t need to be said, but if your primary objective is sales revenue, do not invest in a brand campaign–even if it’s true that, in some circumstances, they can have sales effects superior to those of other campaigns. As a general rule, if you’re looking for quick wins and instant sales boosts above baseline, you shouldn’t even be entertaining the thought of a brand campaign. And if someone is selling you one based on this promise, watch out!

Most people fail to understand brands are more a byproduct of net customer acquisition than any other factor; in other words, brands grow via sales (penetration). Therefore, if the campaign doesn’t result in more sales relative to competing brands, you aren’t really “growing the brand” no matter what you call it. Overlooking this fact is often the source of all disappointment with brand initiatives.

“…Will a brand campaign typically convert to closed-won immediately? Nope. But will it get them into a funnel or move them along? Yes. It all comes down to your attribution model. Personally, I would never expect a brand campaign to close business. I also do not expect a billboard to close business. But both contribute towards awareness and reputation.” – @ohpinion8ted

2. Efficiency

Brand campaigns are not an efficient use of marketing expenditure. This poses problems for smaller brands where budgets are more constrained. For example, 98% of companies in Australia have under 200 employees, meaning the majority of companies there shouldn’t be entertaining the idea of a brand campaign at all. In fact, one of the unique strengths of brand campaigns is their deliberate inefficient use of funds (the costly signaling we mentioned earlier).

3. Small brands

I’ve witnessed many small firms fall into the brand trap because they were desperate for revenue. They misdiagnosed their situation (e.g., stalling or declining sales) and tried to solve it with a risky brand campaign, all because their head of marketing or agency vendor recommended it. Small brands looking for growth would be better off ignoring these temptations and focusing on customer acquisition at all costs. This is how small brands grow into large brands.

The details of this growth process can vary though. You could acquire another company and their customer base with it. Improve distribution or pricing; strike partnerships, affiliate deals, or co-promotions; do sales promotions or referral incentives; or create product ecosystems, communities, direct response advertising, or (yes) even a brand campaign. As you can see, brand campaigns are not the only way, nor should they ever be the default way companies seek growth.

Keep in mind that big brands are often executing a defensive play with their brand advertising. They’re refreshing memories sown many years before. They could also be promoting social causes to meet environmental, social, and governance targets or to cover for previous mistakes. Sometimes, they’re just using it to compensate for deficiencies like poor customer service or product issues. Other times, companies advertise just to keep trademarks legally active in certain countries or to appease investors. Worse, it could be that the lead marketer is burning money to help ensure they get the same budget next year. Even more sneaky though is when firms use game theory to throw competitors off their scent. A flashy brand campaign can be a great way to obfuscate your real source of competitive advantage.

Regardless of these details, if you’re a smaller brand emulating what bigger brands are doing thinking it will “grow your brand”, you’re nearly always mistaken. If you want an example of how to do it without resorting to an expensive advertising campaign, listen to Jon Evans dive into the steps he took for a challenger juice brand:

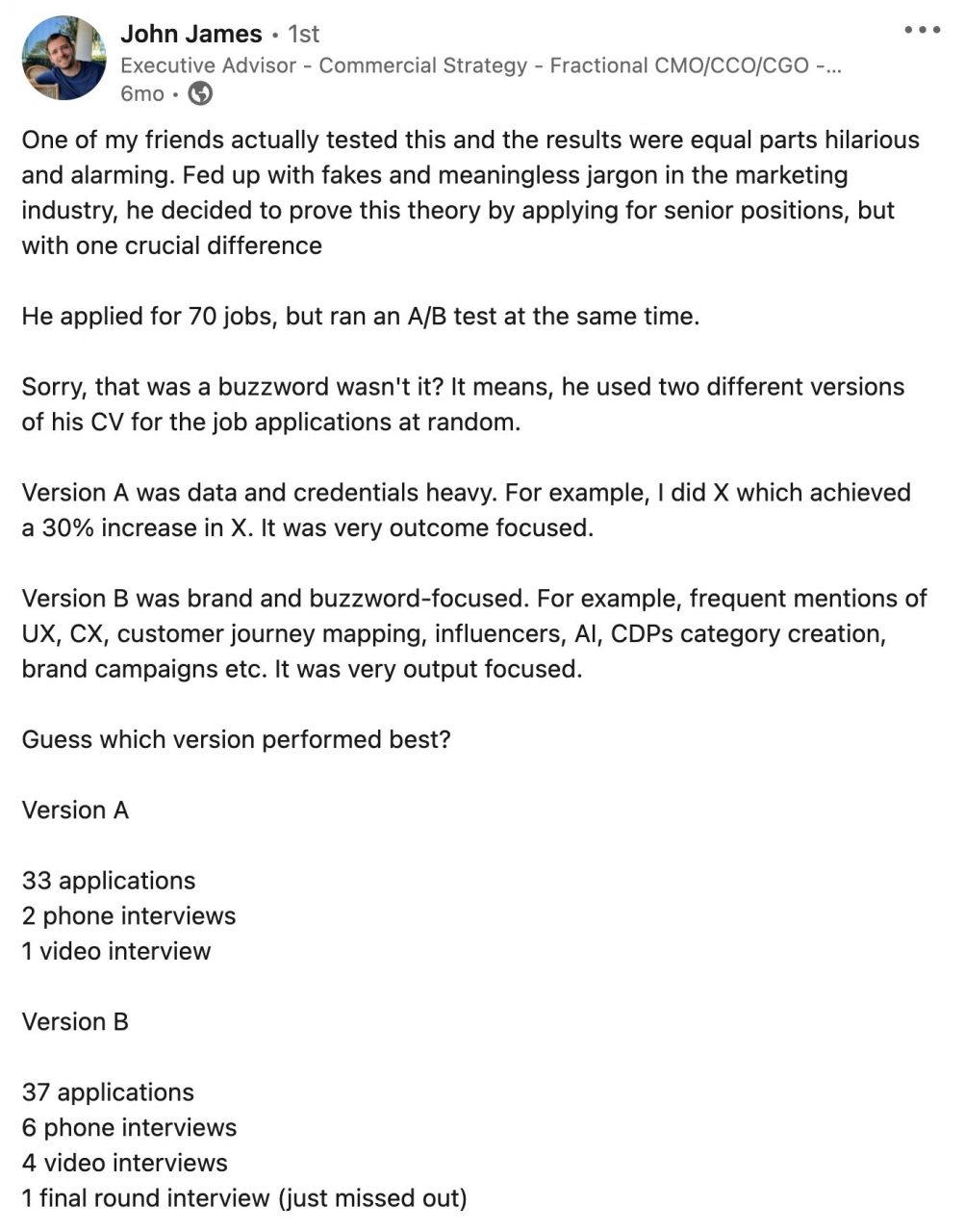

4. Portfolios and politics

There are a lot of career marketers who don’t really care about the business they work for and just want to add a feather to their CV cap. In an interview, if you talk about how you helped increase distribution, optimized pricing, generated 125 leads worth $160k in revenue, or spent 6 months improving operational hygiene…this doesn’t exactly impress anyone.

But if you can show them a slick 90s brand TV commercial that won some awards and claim you were the project lead, it’s much more compelling. Besides, almost no one understands marketing or brand. They love hearing buzzwords and the names of shiny new tech platforms. They’ll fawn over pretty designs and well-produced videos. Unfortunately, visible, rich media–rather than their ability to affect commercial results–is what helps further marketers’ careers. And brand campaigns provide all of this in spades.

Don’t believe me?

“Brand + anything” is very popular with new CMOs that are under pressure to quickly make a mark. They’ll invest in brand campaigns typically as part of a rebrand or refresh. Lots of visible busy work will ensue, together with big promises and lots of company resources.

5. Novelty and titillation

When children are given lots of money and low parental oversight, they typically spend that money on frivolous things for instant gratification. Marketers do something similar. They’ll seek out fun, novel, glamorous, and creative ways to spend the marketing budget instead of focusing on the things the company needs.

Everyone’s got to have some fun at work, but the less supervised marketers are and the lower the commercial oversight, the more this will be the case. By default, marketers will not act in the interests of the company. They’ll avoid sales accountability and invest most of their time in buzzworthy tech and brand fluff. They’ll even convince themselves this work is important and noticed by customers, something Amy humorously explores in this video:

@amy.charlotte.kean FINALLY #fyp #viralvideo #brands #marketing ♬ original sound – Amy Charlotte Kean

6. Pogo-sticking desperation

Brand campaigns are a popular choice after previous efforts–especially sales-focused “performance” marketing–have failed to hit the mark. This instead of diagnosing, improving, or iterating. Immature management will flip-flop back and forth between extremes, often with a new head of marketing, agency, and campaign to boot. They do this because they think marketing is relatively simple and binary.

They’re wrong.

7. Single brand

Brand campaigns make sense if you have multiple businesses or units tied together in a branded house structure, but if you only have one or two products, you rarely need a brand campaign. A better course of action would be to focus on getting the basics right. Acquire customers and use advertising for its strengths. Show your product, make sure it’s clear who’s doing the talking, and connect it with the category you’re in.

Unfortunately, I’ve had to watch first-hand many early-stage, single-product companies invest in brand campaigns and waste large sums of money chasing ethereal brand constructs. Or chasing awareness and fame instead of revenue. It’s painful to witness, and the opportunity cost is so high that they rarely recover.

8. Myopia and strategy

Brand campaigns are often covering up a whole raft of deficiencies within the marketing function. They require less robust research, less diagnosis, less technical skill with media buying (broad targeting), and less measurement accountability. And as we illustrated in Part 1, few people can even explain what a brand is to begin with. They’re the perfect hiding place for brand marketers.

“An expensive ad campaign is the answer. What was the question?” – Anonymous CMO

Brand campaigns arise off the back of unchallenged ideas: “Our brand isn’t [something] enough” or “there isn’t enough brand [something]”. And that’s used as an explanation for why the company isn’t performing as desired. But unless this is validated by proper, independent research (which it rarely is), it’s probably not true.

Brand campaign affinity is amplified for companies operating in highly competitive, mature categories. Here, there can be a tendency to live in denial about the true state of the market, leading to the tendency to chase one brand buzzword–one brand construct–after another. Brand campaigns are proposed as solutions to problems that are actually caused by raw competitive forces. In other words, marketing is often just used to bridge gaps and plug holes.

In these situations, messaging can easily move away from core buying reasons (which help generate sales) and into the brand clouds of ethereal desire (which don’t). When your marketing starts to sound like the kind of yoga-babble WeWork’s founder was sprouting prior to their collapse, you know you’re in the “brand ego tripping” camp.

“‘Brand Laddering’ is one of the most common marketing tools. To drive growth and loyalty, marketers frequently work to elevate benefits of the brand from technical to functional to emotional. But there’s a risk of over-reaching, particularly when brands aim for abstract emotional benefits not really supported by the product story. Brandgym founder David Taylor calls this phenomenon ‘brand ego tripping.’” – Tom Fishburne

Tom goes on to quote David Taylor as he reveals that even the famous “Real Beauty” brand campaign by Dove was firmly rooted in a product context:

“They originally developed three different ‘brand anthem’ campaigns that tried to get women to stop judging themselves so harshly (‘Beauty Has A Million Faces One Of Them Is Yours’, ‘Give Your Beauty Wings’ and ‘Let’s Make Peace With Beauty’). However, as the planner from Ogilvy agency commented:

‘Unfortunately, women were not impressed. They found our ideas patronising. The top-down approach seemed to lead to rather didactic, theoretical and distant work. So we decided instead to work bottom-up – product first, wrapped in beauty theory.’

I love that last line: ‘Products wrapped in beauty theory’. Tell a product story, but in an impactful, emotionally engaging way. This led to the launch of Firming Cream, with the now famous advert of real ladies in their undies. It was fresh. It was honest. And it plugged a product: ‘As tested on real curves’. ‘Real-ness’ and ‘honesty’ was the brand’s personality, but not the idea itself.”

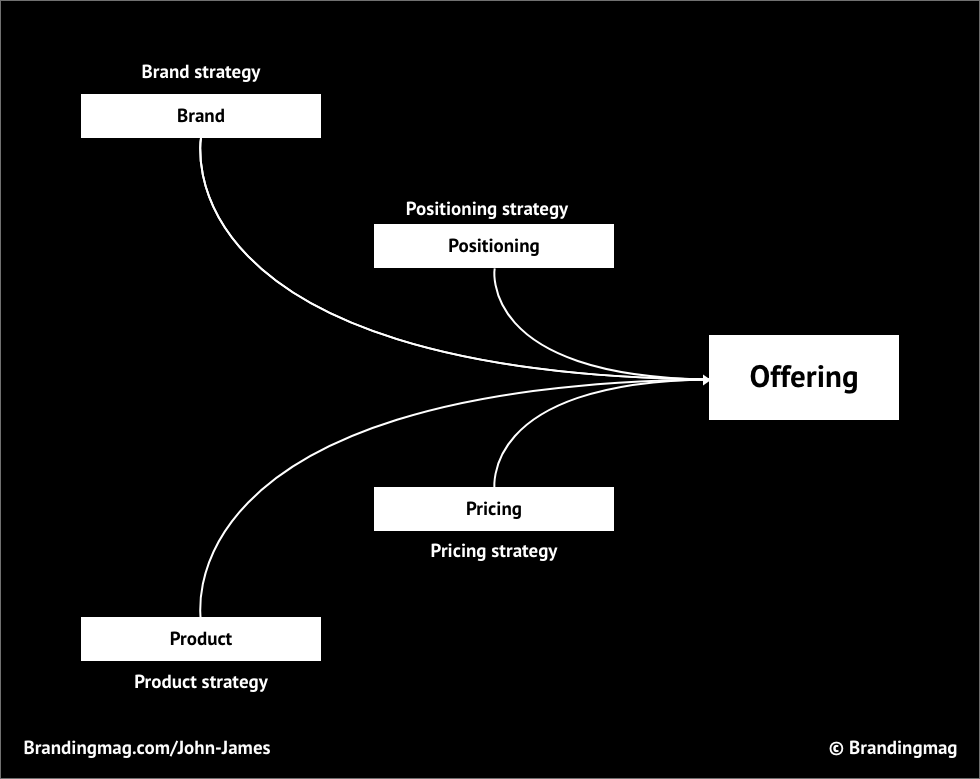

This means that any brand campaign not born from a product context should bring up a major red flag. If your marketing team is trying to convince you that your brand needs to support sustainable circular economies, solve world peace, or hinge on the plight of some endangered animal, watch out! Brand and product are inextricably linked and combine to form your offering. This is why thinking brand is superior and separate from everything else; it’s like saying the key to human health is carbon.

At the same time, focusing too much on tangible, functional product benefits and not understanding all the intangible constructs that can make or break a sale is also myopic. Find a balance. Your offering (the thing customers buy) = Product + Brand.

Lies, more lies, and brand campaigns

There’s a pretty standard list of excuses you’ll routinely hear as to why a campaign isn’t performing as well as hoped. These are the types of excuses you’ll hear from your agency or head of marketing when justifying why a brand campaign isn’t meeting expectations. And it’s natural for everyone to shy away from accountability when something is unsuccessful. But while some of these excuses may be legitimate, others are far from it.

- Time excuse

- It takes time. You need to run it for longer. The creative has to “burn in”.

- We haven’t reached the end of the campaign schedule yet. Just wait a bit longer.

- Creative excuse

- Wait for the second version of the creative to start running.

- We need more/better creative–let’s reshoot. Do another version. A new campaign!

- The creative wasn’t edgy enough to cut through.

- It didn’t work because you made the changes we didn’t recommend (creative dilution).

- Your legal departments and committees got involved and ruined the ad creative we said would work.

- Metric excuse

- But it’s already got [insert correlated volume or vanity metric here].

- Be patient, we’ll see an uptick soon–these things take time.

- We’ll do a full brand recall study after the campaign’s finished. We need to account for the lag effect of brand.

- Budget

- You need a bigger budget to cut through.

- You didn’t spend enough to get past the threshold of attention.

- You’re getting outspent by your competitors. You need a higher “share of voice”.

- We could only do so much with that budget. It was lower than what we said was required.

- Externalities

- The campaign was successful–it must be your product or the macro environment.

- Consumer confidence is down. Look at the news!

- Competitors are outspending you and they’re better–look at their products.

- There’s only so much one campaign can compensate for.

If you read Part 3 of this series, you’ll be able to tell which of these excuses are valid or not. If you’re unsure, reach out and message me. Christopher Lochhead and his team have a great article on the “Big Brand Lie” if you’re interested. It makes some great points, although you should be aware they’re also selling “category design” underneath.

Just remember, any advertising (brand campaigns included) is a great way for vendors to keep their clients on the ferris wheel.

How the advertising industry works pic.twitter.com/YMvLLOGLCy

— John James (@adoseofjohn) September 4, 2023

Can you become a large brand without brand campaigns?

To test whether this is true, all we have to do is find companies that have grown large without investing in brand campaigns. In fact, some of these below have never invested in any type of official advertising campaign!

- Australia: Dominos, Bunnings, JBHiFi, Step One, Harvey Norman, Chemist Warehouse, Youi

- Japan: PKK

- UK: Dyson

- US/Global: Berkshire Hathaway, Zara, Gargill, TSMC, Ryan Air, Foxconn, Tesla, George Foreman, Huy Fong Sriracha, Dollar Shave Club

“Ryanair Tried something like a brand campaign around 2017 – but it was still 99% price + destination and CTAs everywhere… I did an analysis of their spend compared to Easyjet back in the day: Ryanair spent 2/3rds less.” – @colinalewis

We could also look at this another way. We could look at companies who’ve heavily invested in brand campaigns but shrunk, stagnated, or failed completely. While there are too many to mention, some notable examples are Quibi, Uber, Afterpay, John Lewis, Myer, David Jones, and Enron. Curiously, Apple is also quite famous for their 1997 “Think Different” brand campaign, but they haven’t invested in another since. Why? Find out in the upcoming Part 5.

Now, if you’ve read Parts 1-3 of this series and have experience building a brand from scratch (most marketers don’t), you’ll learn that brand is a non-linear revenue opportunity. The mistake people make is believing brands are built quickly and that the best way to do that is by advertising. The sobering reality is that brands are built slowly and mostly via customer acquisition.

Brands work as a halo effect over the entire organization. They operate like planetary gravity. The bigger the planet gets, the more things are sucked into their gravity and the harder it is for things to escape. We all know planets don’t grow overnight (no matter how much we want them to), yet this is exactly how brand campaigns are sold.

Don’t believe me? Hear it from Coca-Cola’s Chairman and CEO, James Quincey, himself:

“In ASEAN and South Pacific, we grew top line and profit by linking our brands to drinking occasions, coupled with strong execution…We continue to see away-from-home channels outperform at-home channels…Within sparkling soft drinks, elasticities are holding up well, and we continue to drive quality leadership with Coca-Cola, Sprite, and Fanta. For example, our systems stepped up in-store activation on Sprite lemonade legacy with increased displays at point of sale, which drove higher household penetration and repeat purchases.”

Takeaways so far

I leave you (for now) with the following summary of what we’ve learned from this series so far:

- Brand campaigns are an agency invention. This should tell you everything you need to know.

- All advertising works along the same first principles outlined in Part 3, regardless of how you want to label or group certain types together.

- There is some merit to using brand campaigns if you’re a large company or if you have a specific brand problem that needs to be rectified.

- Brand campaigns can offer superior political advantages that other marketing activities and campaign types do not.

- Copying a big-brand playbook when you’re small is an error-prone strategic misstep.

- Most people can’t agree on the basic definitions of brand or advertising, let alone explain how they work or are measured. So, purchase brand-related services with extreme caution, especially if you care about commercial outcomes.

And remember, star pupils can mislead

People who argue for the merits of brand campaigns often refer to a few famous advertising campaigns to prove the validity of their opinions. They all love to cite one campaign in particular as evidence of brand campaigns being superior: “Think Different” (aka “The Crazy Ones”) from Apple in 1997. The campaign coincided with the return of Steve Jobs as CEO and was so “successful” that it inspired hundreds of copycat advertising campaigns during the decades that followed.

Just listen to Andy Cunningham (Steve Job’s former publicist) speaking about the campaign:

“I think it was the ‘Think Different’ campaign that took it from a downhill slide to an, ok, now we’re going to go on up. That is Steve’s greatest gift. is that he’s incredibly emotionally intelligent. He understands what people want before they do. He understands what people are going to do before they do, And that’s what he capitalized on when he came back with the ‘Think Different’ campaign. So now he realizes, ok we have a cult here. Let’s protect that cult. Let’s feed that cult and see if we can get it to grow.”

But was this campaign even successful in the first place? Did it provide significant commercial upside for the company? Check out Part 5–where we put everything into practice via an applied case study–to find out, and you’ll be able to decide for yourself.

In the meantime, don’t miss out on the other articles in this series:

- Brand Campaigns, Part 1: What Exactly Are They?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 2: Where Did They Come From?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 3: How Does Brand Advertising Work?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.1: Thinking Different about Apple’s “Think Different” Campaign

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.2: Debunking Apple’s “Greatest Ad of All Time”

“The best marketing doesn’t feel like marketing and the worst marketing is always some type of brand campaign.” – @adoseofjohn

Cover image: Velishchuk