[Disclaimer: Highly recommend you read Part 1 if you haven’t done so already. It’s where we define what a brand campaign actually is.]

Sometimes, to truly understand why things are the way they are, we need to first explore how they came to be. Brands and advertising may have been around for thousands of years, but we often forget that the marketing discipline is still quite young. And brand campaigns? They’re even younger.

Marketing media have risen and fallen in popularity over the decades, but featuring a product in your advertising has always been somewhat of a constant–until brand campaigns came along, that is. And the reasons they came onto the scene (I discovered three) are actually quite interesting: practicality, competition, and culture.

The historical drivers behind brand campaigns

Back in the day, most companies had a very small range of products or services, but in modern times, brands became large enough to support a line of somewhat similar products. Sometimes, these products can be grouped under one brand umbrella (aka a branded house). Advertising tends to be expensive, so it makes sense to lump multiple products into one campaign instead of advertising each individually. This is one reason why Nike doesn’t have to produce individual ads for each product unless they want to: They can just tell the story of an athlete covered head to toe in Nike apparel, instead.

But it wasn’t just practical efficiencies that led to the rise of brand campaigns. They’re also a byproduct of modern competition and business culture. And this battle goes back much further than people think. As you’ll soon discover, the “brand” vs. “performance” tussle is just the newest version of an old theme. So, bear with me; this backstory explains many things necessary for this entire discussion.

“Those who forget history are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

History of the agency battle

Like George says above, if we don’t understand the past, we’re doomed to repeat it. And as evidenced in Part 1 of this series, we already are. By the end of this history lesson, you’ll be able to understand why many marketers have become trapped within binary views on various topics (brand campaigns included).

Genesis

While outdoor advertising is officially the oldest marketing medium, print gave birth to the first advertising agencies. And the first agency belonged to Mr. William Taylor in London. In 1786, Taylor became an agent helping print and newspaper companies sell ad space. He acted, however, more like a pure sales agent for the publisher instead of how we’d describe the typical agency today.

It wasn’t until the 1790’s that another gentleman by the name of James “Jem” White planted the seeds for the modern ad agency. He began testing whether it would be easier to sell print media if he helped the client write and design the ads, too. Turns out it was not only easier, but quite lucrative, as well.

Improvements in print technology and newspaper circulation spurred a spate of advertising agencies across the US starting with N.W. Ayer & Son in 1869, Lord & Thomas in 1873, BBDO (Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn) in 1891 and J. Walter Thompson in 1896. More agencies including Ruthrauff & Ryan (1912), Young & Rubicam (1923), Blackett-Sample-Hummert (1923) popped up during the roaring ‘20s, followed by the launch of commercial radio in the late 1920’s that saw the agency landscape expand even further.

Then, disaster struck. The Great Depression hit hard and funds became scarce. Newspapers became very cautious ad sales for fear of non-payment from clients, so they leaned heavily on brokers to help hedge the risk. Much like William Taylor did one century before, these agents guaranteed payment from advertiser to publisher. In return, they made a cut from the deal–typically, a 10% commission from the publisher, plus another fee (around 7.5-10%) from the client.

Before this, most advertisers would bypass agents and buy space directly, so ironically, agencies benefited from this economic malaise. Larger clients actually found it was more convenient to hire agents, especially when bookings with multiple publishers had to be made. Agents had very quickly become both poacher and gamekeeper. Thus, the principal-agent problem that still plagues vendor relationships to this day was born.

Broadcast boom

As broadcast media boomed over the next few decades, radio, billboards, and TV became big business. High prices and technical creative production meant clients couldn’t do everything themselves, so winning client contracts became a lucrative source of income. The industry was rolling in money, attracting the brightest talent. Agents started banding together into larger groups to better compete and–cue Don Draper–the Mad Men era of advertising was born.

Print disruption

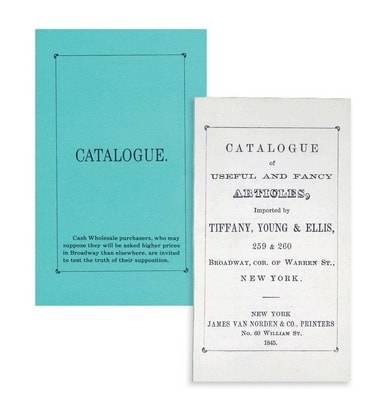

These newer broadcast media disrupted older media like mail-order catalogs, door-to-door sales, competitions, coupons, and signage. Funnily enough, by catalog is how one famous jewelry brand started… Tiffany’s Blue Book, launched in 1845, was one of the first catalogs. The medium became a very popular way for people, especially those living in rural areas, to buy goods directly. So, contrary to popular belief, direct-to-consumer is not a new business model by any means.

Data-driven marketing

While catalogs fell out of favor by the 1950s and 60s, modern postal services, variable printing, and data warehouses sprang up in tandem. These three technologies completely revolutionized print media. Companies could, en masse, send personalized mail directly to customers at a cost lower than ever before. In fact, American Express originally started as an express mail dispatching company; they took advantage of this new tech to launch their first credit card in 1958 via direct mail.

This new way of marketing needed a name. Lester Wunderman, a fan of this media, popularized the term direct marketing–reflecting brands’ newfound ability to market directly to customers via media they had more control over. They could optimize their targeting by measuring the sales effect off the back end. The more mail they sent, the more sales they got; the more sales they got, the bigger the brand became. All for a cost much lower than broadcast media like radio and TV.

David Ogilvy was also one of direct marketing’s main champions. In fact, he was famous for being a big proponent of both direct response copywriting and direct mail. He was also a pioneer of split-testing different ads in print publications to determine which creative was superior. Again, contrary to popular perception, data-driven marketing is actually much older than people think.

The agency divide

Unfortunately, the low costs of direct-to-consumer media also meant potential commissions for sales agents weren’t attractive enough. Direct marketing agencies decided to use a different business model. Instead of relying on commissions, they charged a loading on all the head hours for creative and execution work. This work wasn’t nearly as scalable for the agency, but clients received commercially-focused and effective marketing service in return.

Meanwhile, traditional advertising agencies continued relying heavily on income from media sales–not too fond of the direct marketing model because they couldn’t make as much money. As you can imagine, radio and TV stations weren’t so happy either as they relied on these agencies to sell large chunks of advertising space each year.

This is where the “brand agency” vs. “performance agency” battle arguably begins.

Money vs. scale

The fight was and always has been over money. Brand agencies could scale revenue by selling more expensive advertising media at high volumes, packaging it up with a creative big idea to boot, and limiting their head hours. Direct marketing agencies, on the other hand, made more money by doing the opposite.

Confused as to why they couldn’t get both services from the same agency, clients started asking direct marketing agencies to help with brand advertising, too. Those agencies responded by repositioning their agencies as “brand response agencies”.

At this point, we had advertising, direct marketing, and direct response agencies. Friction between the factions ensued, but a well-known company called Procter and Gamble (P&G) was about to inadvertently put a spanner in the works.

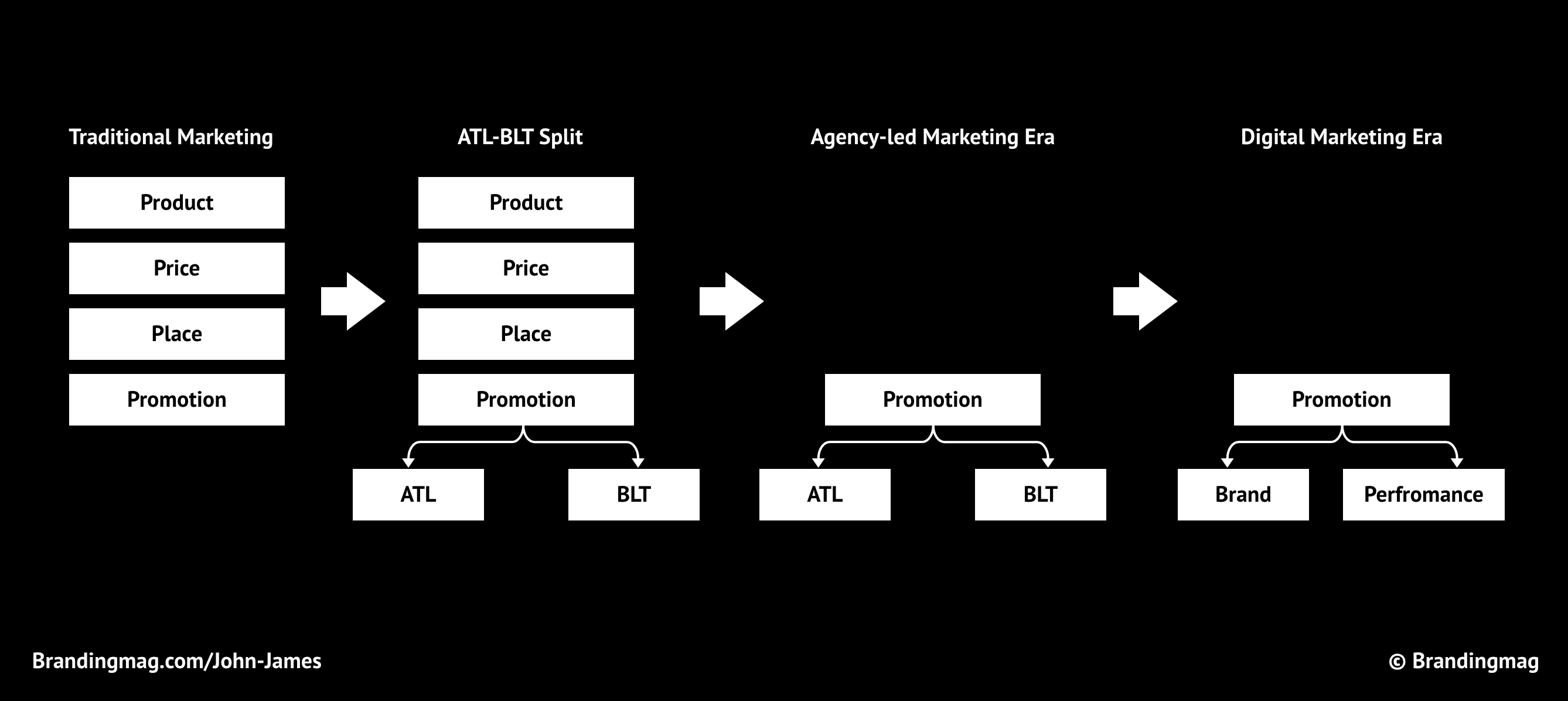

Above-the-line vs. below-the-line

P&G just happened to be one of the world’s largest advertisers at the time. The terms above-the-line (ATL) and below-the-line (BTL) were first used internally in 1954. It’s how accountants delineated different types of marketing expenditure within their budgeting system. Marketers had to separate, with a line, the promotional activity billed by their advertising agency versus all the other promotional activity they ran.

Appearing BTL were internal promotional efforts such as sales promotions, sampling, competitions, direct mail, sponsorships, affiliate deals, and discounts. Larger, more expensive line items (including commissions) appeared ATL. Agencies who serviced P&G became exposed to these terms and usage trickled down throughout the wider marketing industry.

Over time, ATL became synonymous with big brands with larger budgets who could afford more expensive media (like TV, radio, and outdoor). It was associated with more prestigious, higher-status advertising work, while BTL represented the front-line sales-focused work internal staff were often forced to do themselves.

Hollywood actually uses the same two terms with a similar treatment. ATL denotes higher-status staff involved with a film’s creative production, whereas BTL refers to the day-to-day, often lower-in-rank staff. (These terms hold certain connotations–in both advertising and film–to this day.) Advertising and film have always shared a close connection, mostly because making a TV commercial is essentially creating a short film. For this reason, there’s always been a certain level of social cache involved with TV commercial production, and these commercials have traditionally spearheaded “brand campaign” efforts.

Art and creative directors also saw advertising as the first step toward a career in moviemaking, with many leaving the industry to try their luck in film after building up their TV portfolio. Vice versa, movie directors were sometimes seconded by agencies to produce TV ads. Apple’s famous 1984 commercial was directed by Ridley Scott. Scott actually began his career in television as a designer and director before moving into TV commercials and then film.

Until very recently, video production involved large teams of people at high expense. Creative directors, hot actors, catering, glamorous location shoots, etc. It doesn’t take much to understand why marketers enjoyed producing a TV commercial and only serious, big-budget brands could afford to do so. Running a competition, Google search, or snail mail campaign doesn’t exactly hold the same prestige. Nor does it have the same political optics.

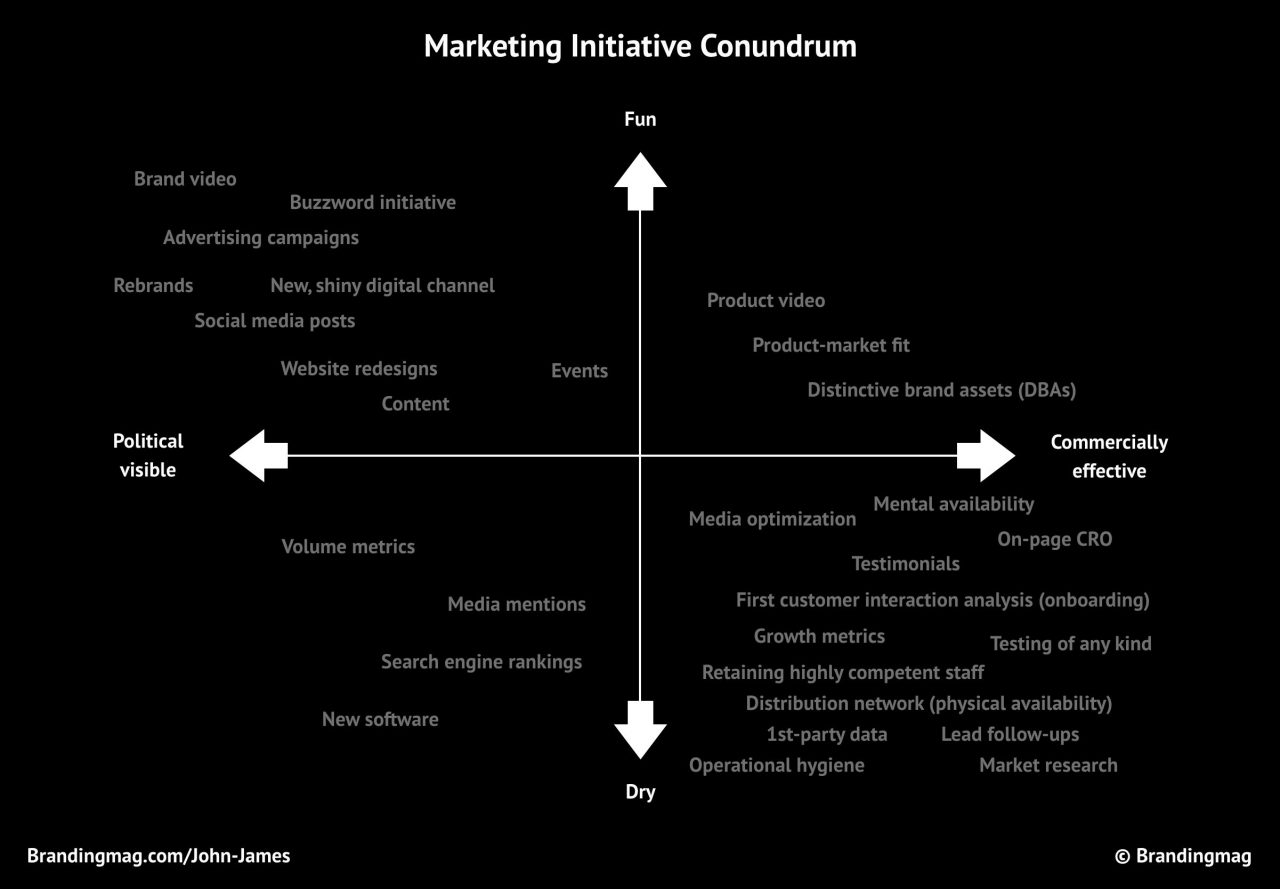

To win politically at large firms, coaches will recommend CMOs to ensure they’re in charge of a large project that uses lots of labor, incurs large expenses, and is hard for people to ignore. Brand campaigns offer all three in spades–executing commercially effective, low-visibility direct marketing initiatives does not.

Brand vs. non-brand divide

By now, holding groups had successfully dealt with the direct marketing agency threat by either spinning off a direct marketing agency or buying one and folding it into their group. But they still took every chance to belittle their enemy. Their business model was definitely superior in terms of earnings potential. With an advertising media sales-based model, any inflation in media cost or addition of new media to the landscape meant agencies could still make more money regardless of how effective it was for the client.

These agencies were incentivized to maximize aggregate billings via media expenditure in order to increase the profit they stood to gain on a percentage basis. It wasn’t about recommending media and services that would help ensure their clients’ commercial outcomes. They were directly incentivized to recommend higher-priced media at higher volumes, more frequently, for longer. Does any of this sound familiar?

How media is bought and sold pic.twitter.com/C6DQbKPW76

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 2, 2023

To cut a long story short, there seems to be a historical carryover effect with these two “categories” of marketing and related media. They’re still treated differently–a stigma that continues to affect business leaders’ thinking and how media channels are chosen today.

The loss of 3 Ps

On the client side, staff were happy to oblige as long as they could get away with it. Besides, their role internally was pretty dull. Their responsibility was for the 4 core P’s of marketing (product, price, place, and promotion). Most of their days were spent in product, packaging, trade marketing, analytics, and reporting. It was effective but hard work and not very glamorous. These people jumped at any chance to escape the office and mix with their fancy agency pals. Making short films together via exotic shoots on location sure beats negotiating distribution deals, working on packaging, or digging deep into spreadsheets.

So, they funneled more and more budget toward higher-cost “brand” media without caring too much about loss of effectiveness. This is when the advertising subset of the promotional ‘P’ of marketing started to break away. It was now becoming such a large part of marketing budgets that a dedicated team was necessary. Instead of marketers being responsible for optimizing the complex system that is product, pricing, packaging, distribution, and promotion, their discipline became fractured and siloed.

Globalization

Globalization in the 80s and 90s increased competition and lowered production costs, placing pressure on legacy brands. Companies that had spent decades investing in production prowess and brand equity were now under attack.

New media disrupted the way we thought about and bought brands. We didn’t need to rely on our memory or neighbors’ opinions. We could do some quick Googling, visit a forum, or post on Facebook to crowdsource the answer instead. Spending millions building brand awareness in target consumers’ minds via expensive broadcast media wasn’t necessary anymore.

Passable, functional product quality became table stakes, a fleeting source of competitive advantage. By tapping into outsourced manufacturing and wholesale networks, every brand could now claim they featured X, Y, or Z. Any differences could be quickly imitated. On top of that, online distribution was starting to erode the value of physical distribution networks. Why support an expensive network of storefronts when you could just sell it all online?

So, as the strategic advantage of product differentiation diluted, the next logical step was brand-level differentiation.

Art of the deal

Around this time was when the agency landscape started to be managed by a generation of commercial optimizers. Media was a big business. Corporate raiders were floating around and executives were always looking for new ways to maximize earnings. Remember, the 80s was the time of the art of the deal (Trump), mergers and acquisitions, roll-ups, leveraged buy-outs, and initial public offerings.

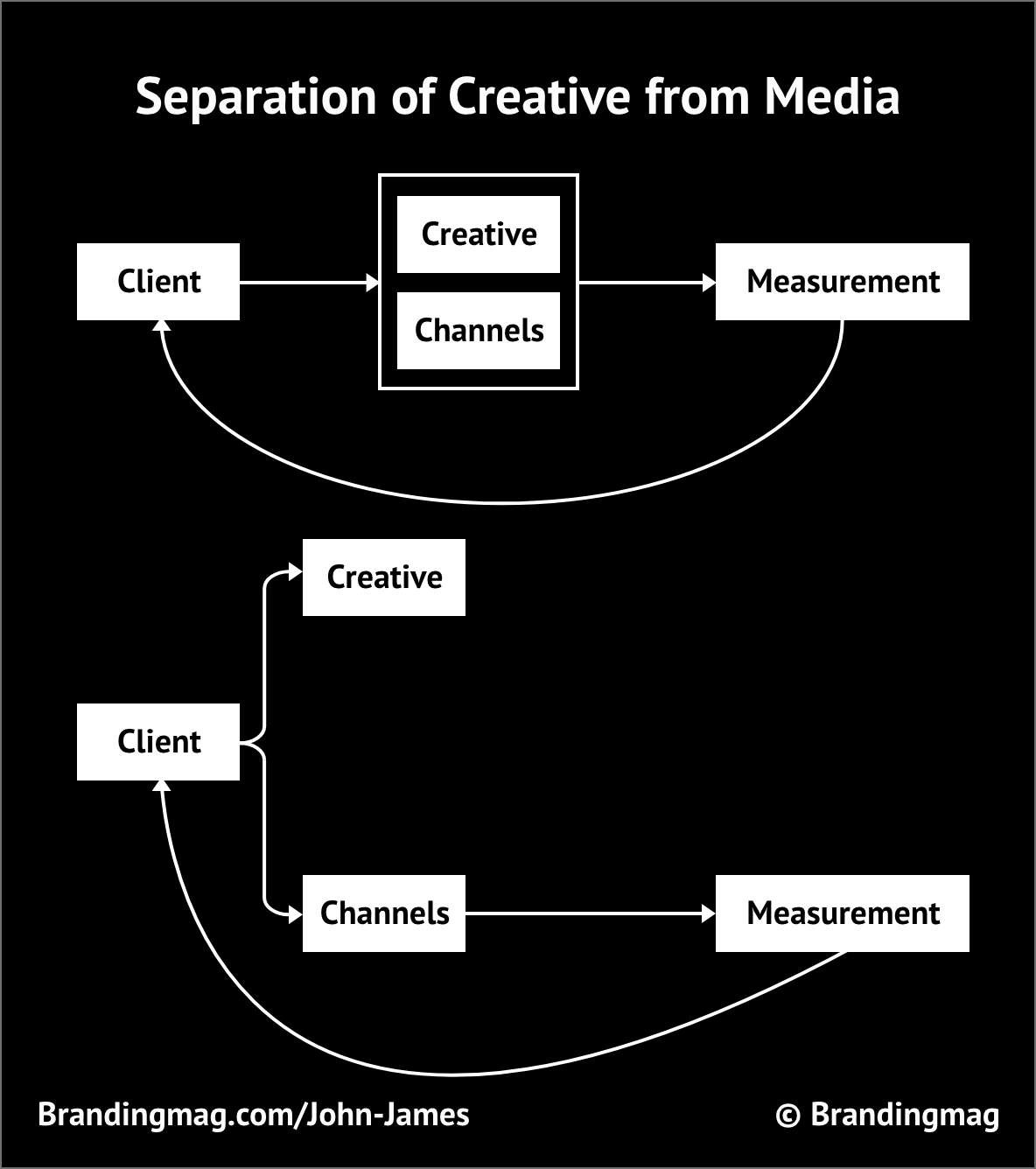

John Hopkins at Ogilvy Australia was one of the first to split the creative and media functions from within the agency in two. Prior to that, creative was often given away for free or at discount rates in order to win new clients. By splitting up a full-service agency into multiple business units, more fees and small percentages of funds could be harvested from all transactions.

Pitch proliferation

While pitching was by no means a new concept, this separation of creative from media further amplified the pitch culture creative agencies now relied on to win work. It also meant the critical connection between the two that’s necessary for effective advertising was now lost.

This trend spread throughout the agency landscape anyways. At the time, globalization and scale was everything in business. You could make a lot of money striking the right deals. A spate of acquisitions and roll-ups followed. Agency groups became so big they transformed into what were now essentially financial clearing houses with a marketing project management arm. The marketing agency mega factory was here (i.e., Agency Holding Co.). The problem was, if your business model is based on making a cut from the entire factory’s production, there’s no incentive to simplify, consolidate, or seek efficiencies. It’s the total opposite, in fact.

Things got complex fast. Agencies popped up left, right, and center, all fighting (sometimes even within the same holding group) for the same client budget. Why? Because there were now so many agencies in each group that they started competing with one another. Agencies then discovered this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. In this era of agency churn and burn, the holding group could lose a creative account in a pitch with one agency but still retain the media account with another. They could lower client churn risk by funneling the media spend back to the mothership.

Meanwhile, clients thought they were switching agencies (due to a house of brands strategy), when their money was actually going to the same corporate entity. Not sure they really cared though, since all they wanted politically-speaking was a new team with fresh ideas working on their account–which they got.

This induced a culture where clients were pogo-sticking between creative agencies more regularly than before. Clients went back and forth between agencies when results were poor or when they needed a change, or when a new CMO was hired. Agencies became the perfect scapegoat for any performance issues. CMOs could easily avoid accountability by churning through agencies.

Digital disruptors

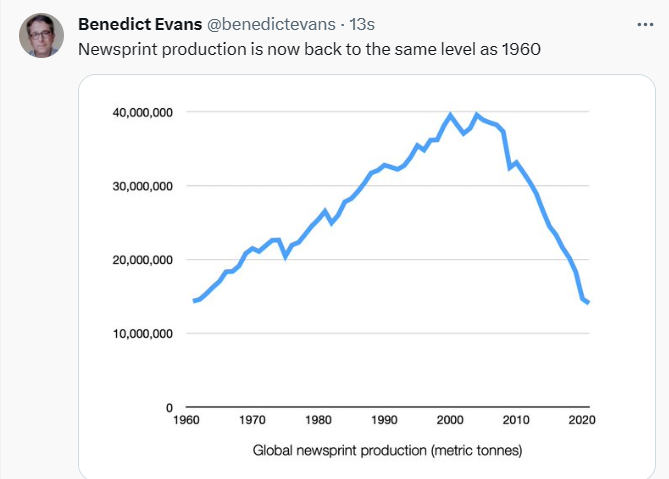

The pogo-sticking went on for a while until the mid 2000s when the rise of Google and Facebook started to rain on the agency parade. These new, upstart digital media platforms weren’t too fond of fitting into someone else’s distribution model. They were busy building all-in-one platforms with do-it-yourself capabilities, commission-free direct payment, and measurement all included for free on the back end.

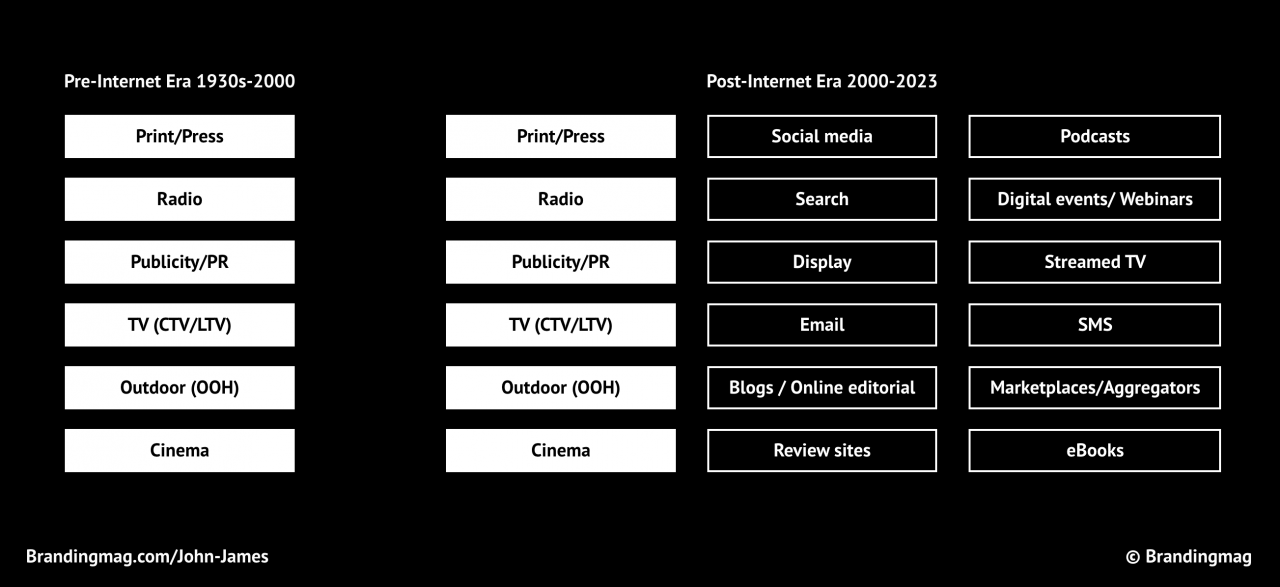

This greatly affected print media (as you can see below). Possibly worse, however, is that the rise of digital media meant you didn’t even need to hire a team of skilled professionals. Dramatic increases in targeting capabilities meant you could both easily reach in-market customers and save large chunks of your budget.

You didn’t need a creative, copywriter, media buyer, strategist, production agency, or even trained marketer. You didn’t need to hire an experienced business development manager. You just needed a 20-something “ninja/guru” who knew their way around Google and Facebook’s ad platforms. It was like dropping money into a gumball machine: You could now target and acquire customers at far lower cost–with the analytics to back it up. Finance departments loved it and more budget started to shift toward digital media.

As you can imagine, this was not welcome news to the high-cost base of traditional agencies, especially since they made most of their margin selling expensive broadcast media. The creative formats mandated by these new digital channels didn’t exactly get a creative designer’s juices flowing either. On top of that, agency suits weren’t keen on buying these media either, mostly (or entirely) because they couldn’t earn commission. All of this to say it’s unsurprising agency groups didn’t like these digital media startups very much at first.

Finding your why

In the Global Financial Crisis fallout (post 2008) a new movement began spearheaded by Simon Sinek. Sinek just happens to be a former advertising agency executive who rose to fame with this 2009 TED talk:

Sinek’s fame was quickly followed by others like Brene Brown in 2010:

Together with their acolytes, emboldened by an era of cheap money, they ushered in a new wave of corporate “thought leadership”. Companies suddenly found themselves entertaining discussions about their company’s why. Gone was the requirement for leaders to be technically proficient and commercially savvy. Modern executives now needed to be empathetic, visionary, and inspirational. Internal culture, social causes, diversity, equity, and inclusion were the new soup du jour. Communicating your values and beliefs became the new currency of a successful corporate career.

Agency connection

Not ones to be left out, advertising agencies caught wind of this trend and started leaning into these themes to win accounts. Instead of pitching campaigns about selling products, they were now pitching brand virtues instead.

Tech companies started talking about how they were changing the world, making it a better place, which helped distract legislators from the fact that they were monopolies. Oil companies started touting their investments in green energy–while making billions selling hydrocarbons at scale on the side. And banks started promoting their commitment to community rescue choppers while facilitating payments for overseas child exploitation.

In this state of flux, a whole new generation of marketers emerged. Instead of being bound by a need to sell products and be accountable for revenue, they now had permission to work on higher constructs. Brand was a place where they could mix with the upper echelons of the company hierarchy and flex their creative muscles at a whole other level. All the big corporations were doing it, so why couldn’t smaller brands do it, too? Like little brothers and sisters, they began emulating their bigger siblings.

Meanwhile, no complaints were heard from the agency side. They rejoiced at the creative freedom these new brand campaigns provided, reveling in the relaxed measurement accountability. Dove started challenging social norms and expectations instead of selling soap. Apple created a cult following by telling us they were a brand for the world’s rebels and trouble makers–going as far as to award ambassadorship to the deceased. Uber’s team started tripping on mushrooms with this corker leading up to their IPO. Unfortunately, touting one’s prowess with atomic particles didn’t have a positive effect on their share price and earnings. (Who would have thought?) And then, there was Bud Light. We can’t forget them. A company who, as it turns out, had the practical marketing nous of college interns. A lesson they learned the hard way.

We can’t lay all the blame on poor marketers though. Executives were approving and signing off on all this expenditure. So, what was it to them? Well…this is where it gets interesting.

Brand campaigns allowed executives to tap the marketing and sales line item for political gain. Not only could they use these campaigns for getting staff onside and attracting talent, but they were very useful for influencing other stakeholders, too. Especially when one needed to redirect investors’ gaze towards a bigger, grander vision of the future and perhaps away from any disappointing short-term realities. Plus, you could look hip and cool.

Divide and conquer

We were now at peak brand hubris. Marketers appeared to be in a competition trying to all outdo one another, seeing how far they could push the brand purpose envelope. But in this haste to jump on the bandwagon, many didn’t pause to consider whether this approach was appropriate in the first place. These campaigns may have been winning industry awards for “bravery”, but if you looked at commercial impact, there was very mixed success. And no one was talking about the brand campaign failures that were piling up.

“Don’t let the internet rush you. Nobody is posting their failures.” – Wesley Snipes

To protect their patch, traditional agencies were now slandering the effectiveness of the digital channels their rivals were selling. They started saying things like digital media were “short-term performance”, “not suitable for brand-building”, “risky”, “not working”, “unable to target older people”, “full of ad fraud”, etc. You’ll notice some of these arguments still do the rounds today. At that time, digital media were becoming so popular, they became a threat that could no longer be ignored.

So, what did the agency holding companies do? They leaned on the same playbook they used in the 60s. They brought digital agencies into the fold via acquisitions or spun-off sister agencies specialized in digital media. Most crucially for this story, they made sure to brand them separately as “performance” agencies. This way the higher-priced, high-status brand advertising work remained protected.

Unfortunately, in this heedy era of brand ego tripping, respect for marketers’ commercial acumen deteriorated even further.

Amorphous ambiguity

With more channels and agencies than ever, the number of phrases that ended in “marketing” exploded. Brand marketing, growth marketing, performance marketing, digital marketing…the list went on. As Matt Watkinson says in this video, you can make a lot of money selling combinations of two or more abstract nouns or verbs. Complexity and confusion also provide more opportunity for vendor billings, as well as lowered accountability for their clients.

Not only did we now have an ever-expanding list of words with a marketing suffix, we also had new categories of agencies added to the list. Creative agencies, media agencies, direct marketing agencies, and digital agencies. Even mobile and GenZ agencies were popping up. Because we couldn’t possibly get all of these services from one!

Katy Dally (former GM at Thinkerbell) summarizes this best:

“…there is this swing back to brand based communication and it’s funny because we all sort of look over there at the shiny new toy, get enamored with it and start running after it. And obviously we saw that with the decoupling of media agencies many moons ago. Why on earth that happened I don’t know. And then sort of the split off of eight specialized agencies. And so everyone’s sort of running in all different directions all the media budgets are following and then all of a sudden there’s actually nothing good in the world. There’s just lots of stuff everywhere and it’s not particularly well considered…

Media is so fragmented. Gone are the days where I recall vividly having the next client brief on my desk which was one thirty second [TV ad] two fifteen seconds [TV ad] one print and one radio and thank you very much. And that is just not how it is anymore. It’s far from it.”

To Katy’s point, instead of relying on one agency to book all media and help with creative production, we’re now forced to deal with a fragmented media environment that is far more complex than it has ever been. This, of course, led to even more competition and arguments over whose approach, channel, or type of marketing was superior. Digital vs. traditional. Performance vs. brand. TV vs. OTT/CTV/BVOD. Commentators had a field day polarizing these arguments and stoking the fire. You’ll notice this tribal warfare still goes on today in some form or another. And while I don’t need to mention names, I’m sure you’ve noticed a string of commentators who specialize in wallowing in all of this confusion. Cue Scott Galloway’s lecture about agency disruption and the advertising industrial complex here.

Today’s situation

Not only has the marketing function itself become splintered and trapped inside a pure communications role, the advertising industry has separated into countless subcategories, as well. While some of the heat from the Sinek/Brown era may have subsided, the allure of brand campaigns remains.

What’s more surprising is how quickly brand campaigns have started to trickle down into the playbooks of some of the most marketing-skeptical companies in the world. Performance channels are now selling brand campaigns to advertisers. And tech companies, now faced with inflated competition and diminishing channel yields, are jumping on the brand bandwagon–albeit starry-eyed–making all the same mistakes everyone else learned the hard way.

Which brings us to the whole point of this article. Why?

Heuristics

What was the point of that trip down memory lane? What you might not be aware of is just how much this historical reliance on agencies has conditioned us to think and act in certain ways without realizing it. There are things we think we understand about marketing, brands, and advertising, things we take for granted each day without pausing to consider whether those beliefs are true.

Making matters worse, past behavior tends to affect future behavior even if that behavior remains a byproduct of a time that no longer exists. What everyone else is doing also influences what we do, even if it’s not necessarily the right thing to do. So, the history of the profession still flavors our decisions–especially when it comes to budget allocation–whether we like it or not.

In fact, I can use this information to predict how nearly every marketing department will operate. Tell me if any of this sounds familiar.

Advertising über allies

One of the simplest tests for prejudice you can do is ask a marketer what’s the best way to acquire more customers and grow. Those who come from an agency or communications background will answer every time with the “P” of promotion (advertising et al).

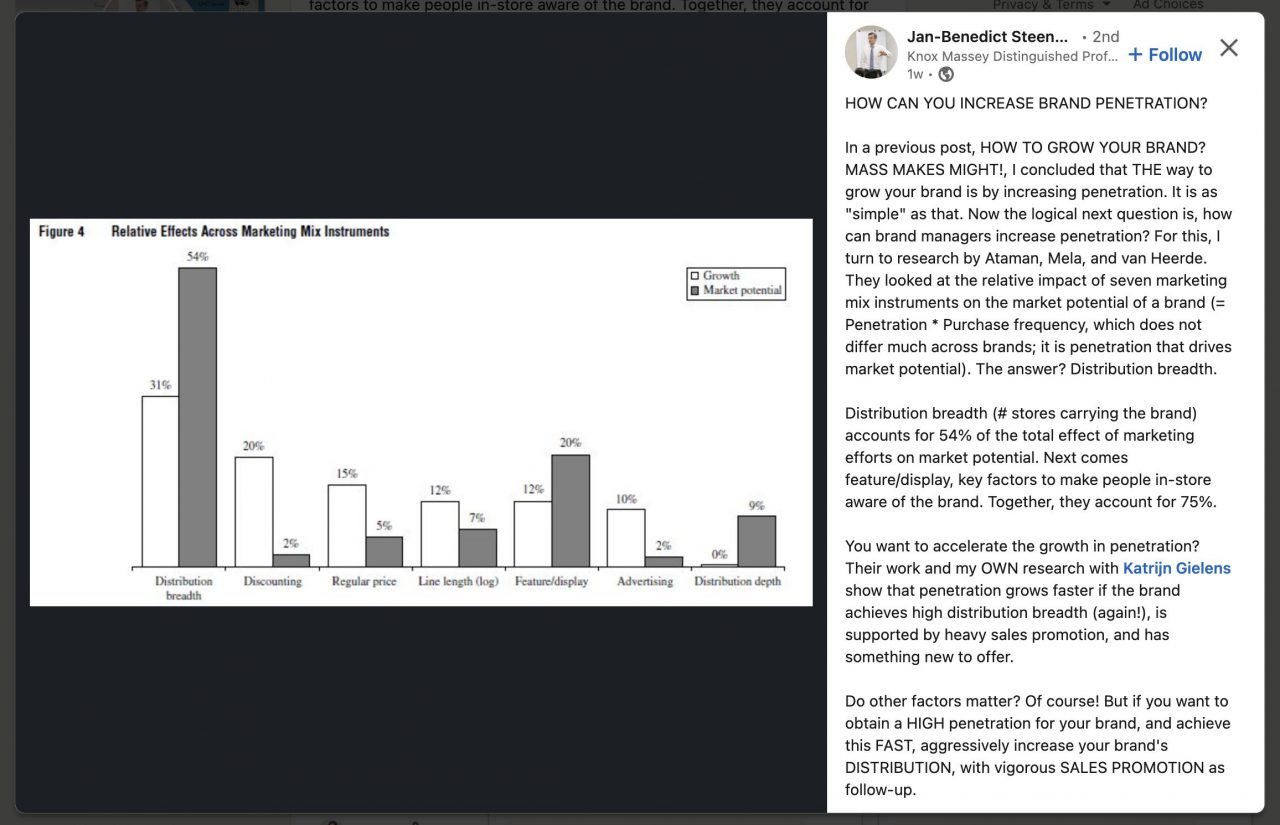

But is this correct? Let’s take one of the prime examples advertising folk love to talk about: CPG or FMCG. If we looked at which “P” is the biggest driver of market potential and growth, research shows advertising is the weakest–and that we should also complement the number one driver with investments in sales promotional activity. Something all advertising folk argue strongly against for fear it will “devalue the brand”.

“If you want to obtain a HIGH penetration for your brand, and achieve this FAST, aggressively increase your brand’s DISTRIBUTION, with vigorous SALES PROMOTION as follow-up.” – Jan-Benedict Steenkamp

Distribution is such a critical part of Red Bull’s operations they even have a separate company dedicated to this function. Same goes for Coca-Cola. Even worse, I’m halfway through a worldwide study testing people’s definition of the word marketing. Early results show that decades of advertising agency reliance has caused the general public (executives included) to believe marketing is just promotions, which partly explains where the Silicon Valley “growth” movement came from.

Vendor squabbling

Competition between vendors for a slice of client budget is perennial. But sometimes, we forget to realize a simple truth: Channels are forced to market themselves, too! This can warp our thought process because it’s something we don’t notice. And they use all sorts of sneaky methods to do this from the creation of contra deals and value banks (which have largely replaced media sales commissions) to discreet sponsorship of marketing industry personalities (who will write articles with a certain tilt), to the infiltration of industry lobby groups. And don’t forget those “independent” research white papers–studies which just happen to show how one channel (or category of channels) is superior to another. Media channels even invent their own metrics to make direct comparisons difficult.

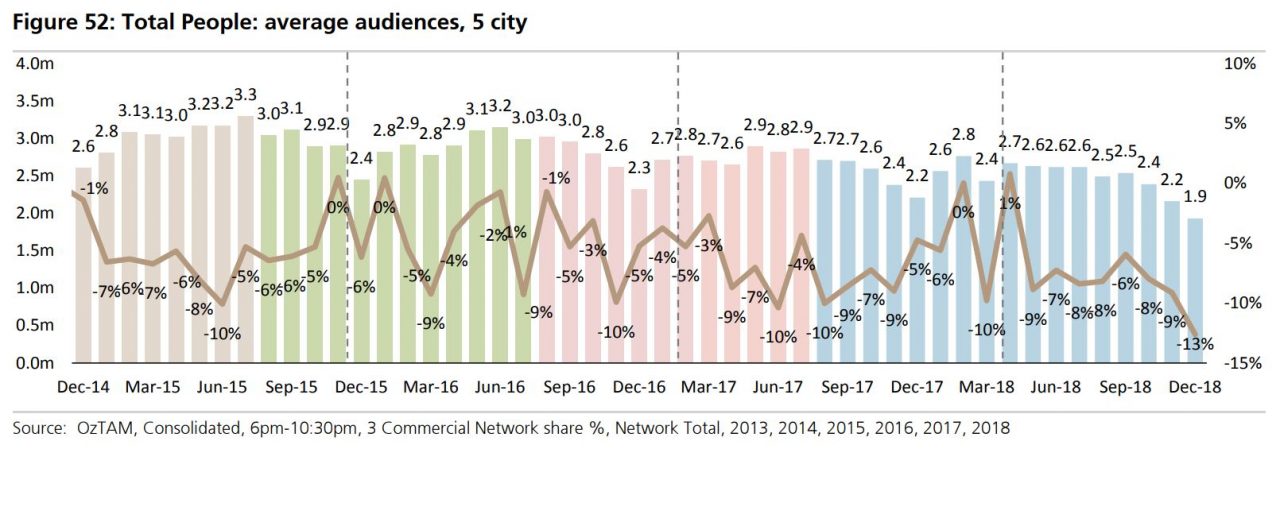

Take Oztam in Australia as an example. It’s a company that measures the state of broadcast media and feeds this information to industry analysts. Spoiler alert: It happens to be owned by a collection of the country’s largest media broadcasters! They used to report on the average combined viewership of the major TV channels in the country (see below). That was until the graph kept showing an unfavorable downward trend.

In response, a few blended metrics were created which combined the old “linear TV” with new streamed versions of TV called OTT or CTV. This way, the numbers showed a rosier story. Locally, the target audience rating point metric is also used for buying and selling TV media, although it’s not used anywhere else. All this time, they’ve been able to keep the price of TV media high even in the face of dramatic declines in human viewership. A job well done!

Complexity = default decisions

None of this is illegal, but it sews even more confusion into an already fragmented, increasingly complex media ecosystem. It’s no wonder business leaders throw their hands in the air and give up. It’s far easier to just take someone else’s word for it or, even worse, force teams to run around like headless chickens trying to cover an unlimited scope of work under the pretense of being “agile”.

The industry is so complex now that weeding the truth out from all the subterfuge often takes more energy than it’s worth. And it’s like this by design. Vendors have learned that if you invent acronyms and increase the complexity, everyone becomes so confused they eventually stop thinking for themselves and follow the leader.

Agency addiction

Have a quick think about the channels you use right now. Why do you use them? Usually, it’s because of distribution. Which means your choices are ultimately dependent on the options vendors provide you, not an independent media planning process.

If you’ve hired a digital agency, they will mostly push website design and development, search, social, display, digital content, and maybe a smattering of other niche digital channels. Most also help with some elements of their client’s IT or marketing operations infrastructure too, which is especially sticky (CRM, data, dashboards, etc.).

If you’ve hired a full-service agency from one of the large holding companies, they will still use the production of a 60-second TV commercial as their central pillar. These then get cut-down into 30-, 15-, and 6-second clips for TV, CTV/OTT, YouTube, and other social media video placements. They will also try to sell full-page print ads, outdoor, radio, digital radio/streaming, display, and maybe a smattering of search and other digital channels on the side (perhaps partnering with a digital, PR, or events firm when necessary).

If you retain a creative agency, they will partner with full-service agencies and digital agencies for media and work with you to execute the creative production of material. You’ll be doing lots of work around brand design, website redesigns, and copywriting. Plus, of course, all the conceptual work for video ads before they get shipped off to a production company to shoot and edit.

Unfortunately, decades of agency dependence has led many senior marketers to stop thinking for themselves. Instead, they’ve become sales agents for the agencies they employ.

How vendors are really selected at your firm pic.twitter.com/HH9zM9TTF9

— John James (@adoseofjohn) June 23, 2023

Commercial vs. political choices

Marketers often find themselves balancing politics with commercial effectiveness. So, while some initiatives can produce step-change improvements in a firm’s commercial performance, they probably won’t be chosen internally, especially not in political environments where status and visibility is key to political survival.

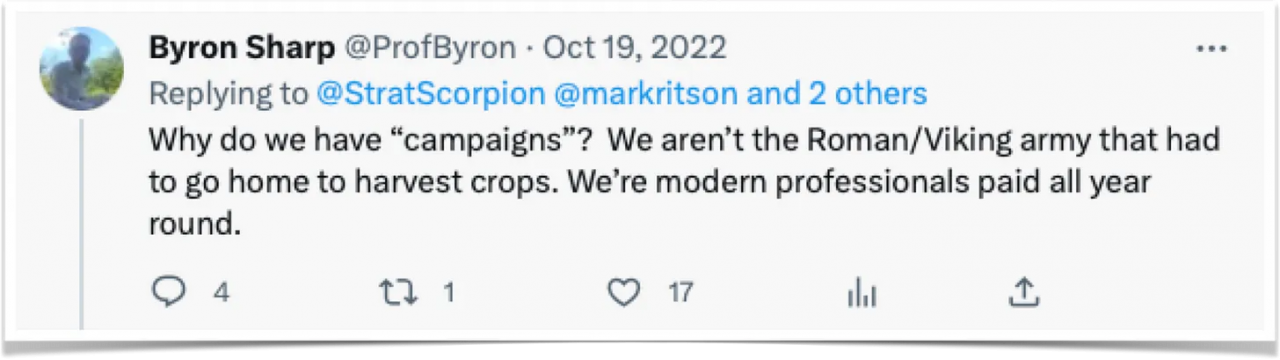

Campaign-first thinking

Why do we call them “campaigns”? Why not do something for an extended period of time? Campaigns are a political construct, sold by agencies and willingly accepted by clients. But customers don’t think in campaigns.

So, why does so much of marketing revolve around campaigns? Because just like any project, stakeholders can attach themselves to a campaign and use that project’s success or failure as political leverage.

Up next: Find out how all advertising (brand advertising included) works or doesn’t work in Part 3 here.

And don’t miss out on the other articles in this series:

- Brand Campaigns, Part 1: What Exactly Are They?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 4: Why and When Should You Use Them?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.1: Thinking Different about Apple’s “Think Different” Campaign

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.2: Debunking Apple’s “Greatest Ad of All Time”

Cover image source: tuayai