In case you got the wrong idea, I’m not anti-advertising, anti-agency, or anti-brand. I just don’t have the luxury of entertaining company activity that doesn’t contribute to the bottom line. That’s because I specialize in commercial strategy, a chunk of which involves measuring the financial returns of marketing investments in order to optimize the expense. And because the majority is always wrong when it comes to high performance, you’ll get a very different side of the story from me than what prevails throughout our industry.

Now, before you read this, I highly recommend reading at least Part 4 of this series. That’s where we explored the 16 pros and cons of brand campaigns, many of which reveal themselves throughout this real-life case study. While you’re at it, Parts 1, 2, and 3 wouldn’t go astray either. If you’ve read them already, then you’ll understand why I say it’s too simplistic to have binary views on the marketing discipline.

We don’t live in a world where there are simple black or white answers to an incredibly complex profession. But unfortunately, many people seem to believe in false dichotomies, especially when it comes to the topic of brand. Brand campaigns are somehow over to one side, busy building “brand”, while all other campaigns and activities are some place else generating sales (or whatever they’re supposed to do). This, as we demonstrated in Part 3, shows a fundamental misunderstanding of how advertising works.

The problem with brand campaigns in particular is that the concepts are so intangible that the campaigns sold by scammers versus those sold by skilled professionals can appear identical to the untrained eye. Which is why I’ve written this whole series in the first place–so you can learn to spot the difference.

Fair warning: This part of the series goes pretty deep into analyzing Apple’s famous brand advertising campaign. I can already hear you saying, “Why do you have to hurt my brain again, John? I can’t take this anymore!” But it’s our failure to dig deeper that perpetuates these falsehoods in the first place. So, it’s kind of necessary.

Good news is I’ve spent months doing all the digging and heavy lifting for you. All you have to do is grab your favorite beverage, find somewhere comfortable, sit back, relax, and enjoy the show.

The crazy ones

Remember Apple’s famous “Think Different” commercial? The one Steve Jobs launched on stage in 1997 talking about how important it was that the brand rediscovered its identity? How Apple needed to define what they stood for in order to compete in a noisy world? It’s one of those rare videos that does the rounds on LinkedIn and Twitter feeds on heavy rotation (not common for a video from the 90’s). The TV commercial that follows his speech is iconic and, by all accounts, was a roaring success.

Steve said the ad was made so Apple could better communicate their values to the market and refresh a brand suffering from neglect. Because that’s the secret to effective advertising, right? Finding your “why”, your brand purpose, and communicating it to the world. It’s what we’re all striving to do as we follow Patagonia’s footsteps.

Well…turns out that’s not why this Apple ad was made.

It was made so an agency could get their client back. It was made even after Steve firmly rejected it. But most of all, it was made because, quite simply, they had nothing else to talk about. Lucky for everyone, it just happened to become a global hit and is now admired the world over.

The more I dug into this campaign’s backstory, the more I realized how misleading this viral video really is. Few had bothered to question the campaign’s real impact. I know I hadn’t. And this has led to decades of copycat behavior based on a mixture of half-truths and lies.

So, here’s the red-pill story if you’re game to hear it. The full story–including many parts you may find surprising–to the best of my knowledge. It’s quite different from the dominant narrative within marketing circles and reveals some inconvenient truths industry folks probably don’t want you knowing about.

This may change how you think about advertising forever. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Defiling a deity

A few months ago I sent advertising Twitter into a tailspin by suggesting brand campaigns were a scam. In the comments that ensued, a lot of people kept referencing this particular Apple campaign as counter-evidence, motivating me to dig deeper. What exactly was the original purpose of “Think Different”? How did the idea start? What short- and long-term effects did it have? Surely a campaign of this magnitude would easily reveal itself in Apple’s financials. And yet, this is where things got even more interesting because it didn’t.

But “Think Different” (a.k.a. “The Crazy Ones”) is a multi-award-winning TV commercial, frequently labeled one of the best ads of all time. Best for whom, though? How do we even judge effectiveness in the first place, and what did the campaign do to Apple’s bottom line? Because brand values, beliefs and awareness are all great, but senior marketers know that if you want respect at senior levels, commercial impact is the key.

When you ask marketing what the campaign did? pic.twitter.com/oNoJPzNA9M

— John James (@adoseofjohn) November 12, 2023

Yet Steve’s speech above wasn’t impromptu. It was rehearsed. Actually, this particular announcement is also an extreme outlier. The entire campaign, in fact, is an outlier because it’s one of the only–if not THE ONLY (correct me if I’m wrong here)–Apple campaigns that doesn’t mention a product.

If you watch that video again–very closely, with fresh eyes–you’ll notice just how rehearsed it is. The hand to chin pensive poses. Intentional pauses and gestures at just the right time. Eyes down at his feet when talking about struggles. Glancing up to the crowd with forlorn eyes just as he makes an important point. It’s a world-class example of persuasive delivery.

And persuade he did. Steve was a master communicator and this speech sets the scene perfectly for what comes next. He’s priming the audience and pre-selling the creative idea even before the film starts to roll (something every advertising exec knows is key to a successful pitch). The 60-second TV commercial that follows is simply a piece of art to spearhead Apple’s first brand advertising campaign in 6 years.

But is it too good? Are we getting trapped inside a halo, basking in the glow of Jobs’ aura instead of assessing the campaign and Steve’s foresight objectively? Was Bill Burr right?

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a brilliant speech either way–a speech that makes marketers nod in agreement as they sense the irresistible urge to tag their CEO in the comments. And the ad remains a brilliant piece of moving image that’s so engaging, creative directors consider sacrificing their fedora collections to the advertising gods.

But at the same time, every fan of the ad I came across had no idea why it was created. And it seems the story has become so embellished over time that much of the original truth has been lost, which wouldn’t be an issue except that marketers still use it to justify something the campaign was never intended, nor achieved.

History is written by the victors

“Think Different” first aired September 28, 1997 at the tail end of that year’s $90m annual advertising budget. Apple bought big. Airing first via two prime-time slots during the debut of A Toy Story (Pixar film). This premium TV buy was heavily supported by other broadcast, print, and outdoor media running late into the 1998 financial year.

You have to remember, this was a time before digital media was a thing. YouTube wouldn’t be launched for another 8 years! E-commerce was a foreign concept to nearly everyone and the World Wide Web was in its infancy. In this era, TV was lucrative because it could capture massive swathes of public attention in one fell swoop.

The ad creative was world-class. The media buys were smart. And “Think Different” quickly became an iconic ad, winning a slew of industry awards along the way, praised by critics worldwide. It leveraged the power of a simple message delivered in poetic fashion to devastating effect. This choice of creative was a significant departure from competing ads at the time that were product functionality-focused. Feast your eyes on this classic as an example:

After Steve rolls the commercial, he explains the crux of their new media strategy:

Steve Jobs’ explaining the media spots for the Think Different campaign. Part 5 of the article series dropping soon! pic.twitter.com/bVH6hOZuwK

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 30, 2023

This campaign became so iconic, it inspired a whole generation of people around the world. A string of books about Apple’s design philosophy hit the shelves. Copywriters became so enamored with Apple’s inspirational prose that they emulated the writing style for other clients. Leaders emerged from the shadows of the boardroom to launch products on stage, as well. Executives even started talking less about financials and more about company values. People started dressing like Steve, which led to a shortage of turtleneck sweaters in the Bay Area. “Think Different” cults sprang up. Decades later, even Elizabeth Holmes would tap into Steve’s 90s image to the disadvantage of her investors.

And today, marketing commentators continue to heap praise on this campaign. It’s become a poster child of sorts (for creative directors especially) on the virtues of brand advertising. Many marketers believe this ad is a timeless, shining example of advertising done right. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who would tell you otherwise.

But, is it?

Correlation–every marketer’s favorite snack

The idea for writing this article came to me years ago while watching a YouTube video. In this video, a marketing commentator attempts to explain the reasons for Apple’s stock market success. This person speaks in a way similar to how most marketers speak about marketing they love. They talk about how brilliant the ads were before going on to claim these campaigns were responsible for the company’s current financial position.

And while this might be true on rare occasions, what’s more telling is what’s omitted from the discussion. Product, distribution, and pricing are rarely mentioned. Not to mention less glamorous promotional activities like sales activation or point of sale. Nor is business strategy mentioned–neither partnership deals, ecosystems, network effects, talent, nor R&D. And especially not investor relations and financial mechanisms.

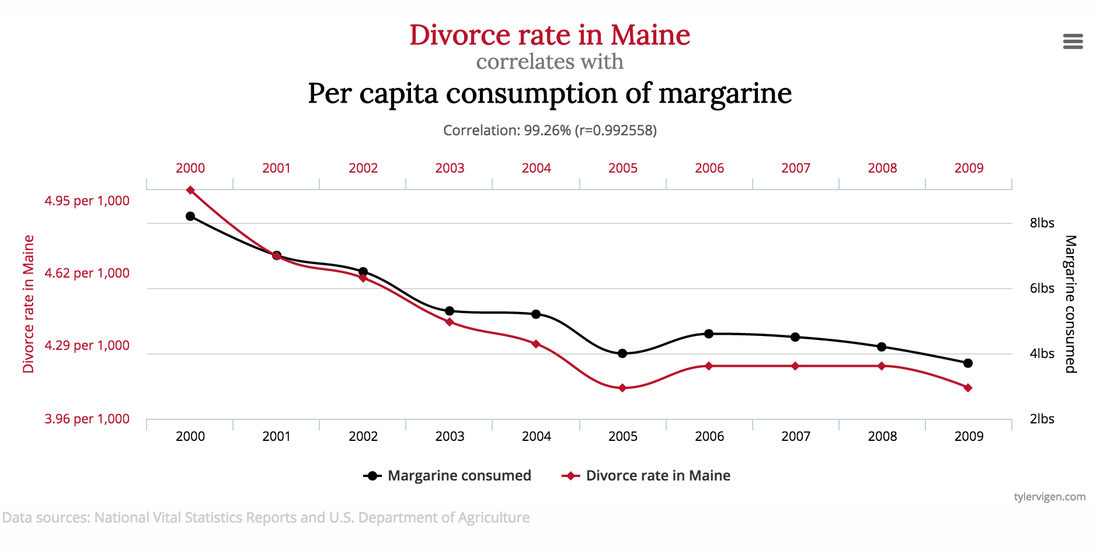

There’s nothing wrong with this, sure. I mean, we can’t all be experts in everything. But it’s a common trap even the most experienced marketers routinely fall into. An oversight (mistaking correlation for causality) that actually stymies their executive career potential. Here’s an example that shows just how easy it is to make this mistake:

There’s a whole page where this came from if you fancy a chuckle. My personal favorite is still…

In truth, many factors contributed to Apple’s financial performance at the time, and the same goes for any company. It’s myopic to attribute any single business function, let alone one advertising campaign, to a company’s financial performance without considering all the other variables.

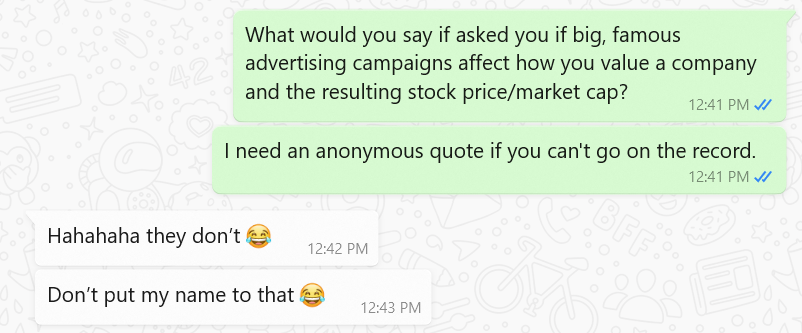

A colleague of mine just happens to specialize in public company valuations in the media and technology sector. He’s worked for some of the largest investment banks in the world, so I asked: “What would you say if someone claimed that one ad campaign (or a series of them) had a significant impact on a company’s public value?”

Once he stopped laughing, I pressed for a longer answer. Putting down his Caldwell Cigar and gently resting a glass of Macallan 25 onto its ivory coaster, he opened the top button of his Super 130’s Zegna suit, leaned over, and said…

“An individual campaign is almost always going to have a negligible impact on valuation.

One of the most important things analysts are trained in is to not get caught up in the hype and emotion these companies try to generate. To quote Warren Buffett, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.’ Capitalizing higher earnings as a result of one campaign into perpetuity is almost always going to drive an unsustainably high view of the business’s future earnings and its valuation.

Individual campaigns are unlikely to drive meaningful long-term valuation uplifts because, how can you measure their impact in 1, 2, 3, or 10 years time? Maybe they can boost near-term sales at best. A business’s valuation should be based on your view of the net present value of all future earnings.”*

*P.S. If you want to get a seat at the boardroom table, you need to understand these bolded terms.

A finance personality on Twitter takes this a step further, making the humorous point that market value is even more divorced from a company’s activity and earnings than many believe. Whether you agree with him or not, it would be misleading to overlook macro-economic factors or ignore everything else that was going on internally at Apple while “Think Different” was circulating.

Employees: Why is our stock down?

Me: Ummm… Interest rates. Student loans. Ozempic. Jerome Powell. Recession fears. War in the Middle East. Oh and a company that kinda does what we do but not really did poorly

Employees: Wait, nothing we do matters?

Me: No, no, not at all

— BuccoCapital Guy (@buccocapital) November 2, 2023

The complexity of commercial success is hard for many people to grasp. Thinking is a high-energy activity, and there’s a natural tendency for us to simplify things down to more digestible, easier to understand versions (reductionism). Then, we tend to select one or two variables from the entire mix (selection bias), make sure they align with / reinforce our own belief systems (confirmation bias), and claim that these factors contributed most to the final result (attribution bias). It’s simple, and it feels good–but it’s more often than not, wrong.

In fact, there’s one major omission in the viral Steve Jobs video we referenced earlier. And it’s the first 3 minutes of the talk! At the beginning, Steve gives the audience an overview of the turnaround strategy where he details the other 3 P’s of marketing (pricing, distribution, and product). Yet this part doesn’t make the cut in the 6-minute version marketers post on social media. Why? That’s a good question.

The start of a famous Steve Jobs’ speech that’s omitted by marketers. Part 5 of the article series dropping soon! pic.twitter.com/j9sNJd1yCj

— John James (@adoseofjohn) October 30, 2023

The political dynamics at play in our professional lives also provide a strong incentive for us to ignore what is true. If you’re a marketing commentator with various advertising industry sponsors behind the scene, it’s only natural for you to project a certain “pro-advertising” line. As an agency, you’ll cherry pick information from case studies to help retain clients or win new ones. And as a CMO, if you don’t claim credit for success, someone else certainly will.

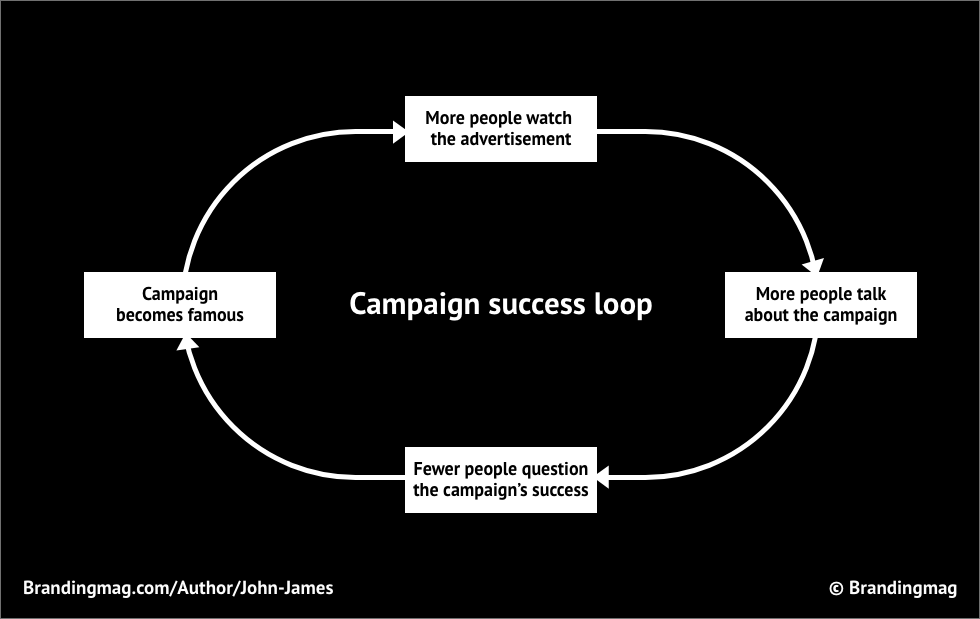

All of this means there’s little incentive for any of us to question the validity of “successful” campaigns because they can have both political and commercial value. The problem is that this creates a self-reinforcing loop.

“Don’t let the internet rush you. No one is posting their failures.” – Wesley Snipes

Mr. Snipes seems to be well aware of the concept of survivorship bias, and the same applies to marketing campaigns. Few talk about campaigns that fail and even fewer question what makes the others “successful”.

The tweetstorm

That said, it wasn’t totally unexpected when some advertising industry personalities became defensive after I criticized their deity’s (brand campaigns) effectiveness on Twitter. They immediately went on to reference famous ad campaigns from Apple and Nike as irrefutable proof points. In their eyes, “Think Different” and others like it provide concrete evidence of the superior role brand campaigns play in company growth, especially when compared to the evil nemesis that is “performance marketing”.

Not only were these people insulted by my reference to brand campaigns as a “scam”, they were adamant “Think Different” was effective. Oh, and I was an idiot for even daring to question it. But when asked for evidence, these same voices became silent, struggling to provide concrete evidence or figures (not that I could at the time either). Nor could they define with any consistency what a brand campaign even was, which was strange. How could they believe something was effective if they can’t first explain what it is we’re all talking about? (See Part 1 for the answer.)

Now even more intrigued, I wondered what commercial impact this campaign actually had. Had anyone bothered to crunch the numbers? Or were we all just relying on second-hand information and taking someone else’s word?

Lucky for you, I went through the trouble of finding out.

Romeo returns from exile

Just like any good Shakespearean play, we first need to set the context of this period because it will become important. Two computer companies, both alike in dignity, in fair Cupertino, where we lay our scene.

It’s 1997. Jobs has just returned to the CEO helm after Gil Amelio left following a period of poor performance. Apple was left holding a large portfolio of products which weren’t selling particularly well. They were also rapidly losing market share to upstart rival duo IBM/Microsoft. Investors and customers were nervous, and Apple was facing the grim reality of bankruptcy.

But Jobs’s return was no light appointment. Even though he co-founded the company with Wozniak back in the late 70s, there was a history of bad blood with certain board members. In fact, Steve’s last stint as CEO ended unceremoniously following a power struggle. This forced departure in late 1985 by all accounts left him quite spiteful. But to his credit, instead of wallowing in anger, he founded two new companies. Pixar and NeXT Computers both ended up becoming successful multi-billion dollar companies in their own right. Successful enough for others to notice–and notice they did.

According to MBA Knowledge Base, “Microsoft’s release of Windows 95 in 1995 forced Apple’s CEO, Dr. Amelio, to respond with the release of their next generation operating system code-named ‘Copland’. But Copland was so behind schedule they looked outside the company to purchase a new OS, ironically deciding to purchase NeXT Computer from Jobs. The board became impatient with Amelio when sales didn’t rebound quickly enough and he was replaced with Jobs.”

So, Steve was only returning to Apple as part of a software acquisition deal–one that also included a range of personal computers being used by people like Tim Berners Lee at the time. It’s also easy to overlook just how old Apple was at this stage. Founded in 1979 and public since 1980, Apple was a very mature, multi-billion dollar company when Steve returned. Their first brand campaign (“1984”) and their second (“Think Different”) occurred 8 and 22 years after their IPO–an especially important fact to acknowledge if you’re a small, early stage company thinking about investing in a brand campaign like Apple. “1984” may have been lauded by marketing industry pundits and touted as the best ad of all time, but it actually didn’t fare too well commercially (or help further Steve’s executive career).

World’s Best Ad… or maybe not? 🤔

Sales Decline: After an initial strong interest, the sales of Macintosh couldn’t sustain and started to decline.

Layoffs: Apple laid off 1,200 employees, which was about 20% of its workforce in 1985, due to financial struggles.

Leadership… pic.twitter.com/7t5vacWSdb

— Brat V (@bratinceptly) November 2, 2023

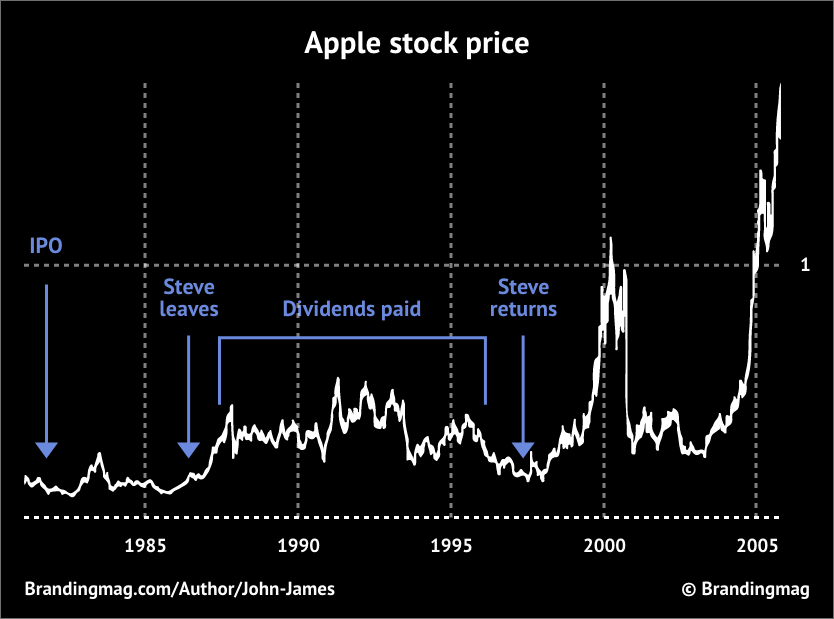

But that’s a story for another time. The problem in 1997 was a financial one and investors were losing confidence in Apple’s leadership, a predicament reflected in the company’s stock price and market cap.

To illustrate just how bad things were, Apple’s market capitalization (stock price x number of shares) when it first floated in 1980 was $1.8bn and, by the end of December 1997, dropped to $1.6bn. This means that, in the 16 years since their IPO, Apple had decreased in value. Making matters worse, they had incurred large losses in the 2 years prior, totalling a combined $1.87bn! So, when Jobs returned, he was immediately under pressure to turn the ship around…and quickly.

The stage was perfectly set for someone to sell a turnaround strategy, improve performance, and claim all the credit for it. Lucky for Steve, his timing was impeccable because this would coincide perfectly with the tail end of the dot-com boom.

Clearing the decks

Contrary to popular perception, Steve started his turnaround strategy with another marketing “P”: product. One of the first things he did was refocus their product portfolio, cutting poor performing ones and initiating the development of new ones.

The Pippin, Apple Quick Take, and the over-priced 20th anniversary Mac were all cut, followed by the Newton PDA a few months later. He also phased out software license deals they had with other computer manufacturers, which many schools were using at the time.

In fact, he cut so much of the product range that, by the end of 1997, only 4 products remained. 70% of the product portfolio was gone, along with 4,100 employees! But these cuts helped immediately lower expenses and took some pressure off earnings in the short term.

Executives always like quick wins. And just like a new coach hired for a team rebuild, Steve was being decisive and delivering straight out of the gate. He was squarely focused on setting Apple up for long-term growth. But we all know you can’t cut your way to growth. So, in August 1997, he also leveraged a legal predicament Microsoft found themselves in to convince Bill Gates to invest $150 million.

Fresh talent was next on the list. The board was overhauled and key hires were made, including people like Johnny Ives who ended up being a pretty good choice. A new, leaner, meaner Apple team then got to work designing new products that would form phase two of the turnaround.

Product trinity

While “Think Different” was still playing in the background, 10 months of R&D finally resulted in a new product that kickstarted the growth phase. In August 1998, iMac was released. It was colorful, distinctive, fairly priced, and packed lots of computing power in a visually attractive box. Luckily, it was also an instant hit, becoming the first product to start a new cult following that “changed the world”.

By this time, “Think Different” was still in circulation but was playing second fiddle to product-specific campaigns, starting with “Un PC” to promote the iMac:

The release of a portable computer iBook followed in 1999. It targeted a similar audience, a segment Apple believed had been underserved by the monochrome products that dominated personal computing at the time. And it wasn’t just their ads that were distinctive. Apple’s products were distinctive, too. Instead of dull gray and black boxes, Apple products were now brightly colored, curvaceous, and quirky. Both the iMac and iBook sold well and revenue trickled in. Momentum was building.

By the early 2000s, the “Think Different” campaign was no longer the promotional star of the show, having been reduced to a limited number of print and outdoor ads. This is important to note when we get to the financial analysis in a minute.

In 1999, Apple launched the “Hal 2000” campaign promoting Macs, followed closely by “iMovie” in 2000 and “Beat” in 2001 promoting the iPod. All of these campaigns explicitly showcased products in the ads. None were what we would call “brand campaigns” nor did they reuse any elements from the “Think Different” campaign. And by 2002, Apple would stop using the “Think Different” campaign altogether.

So, what did “Think Different” do?

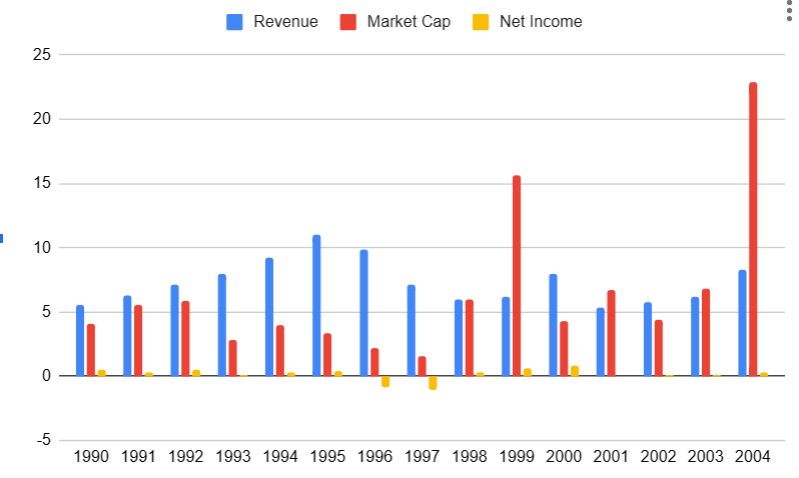

Did this famous brand campaign do anything during its lifetime (1997-2002)? Let’s quickly look at some key financial measures around that time period.

At face value, you might say the campaign had a mild short-term effect on market capitalization (red) and profit (yellow), but I was expecting to see a much larger bump. Especially for such a famous campaign. By 2002 (5 years later), it even appears Apple was back to where they were 12 years earlier (1990).

I can already hear you say, but John…

- Market capitalization increased–look at 1999!

- Profit was positive for 3 years after 2 negative years

- Revenue stabilized and then increased in 2000

- Brand campaigns can have long-term trailing effects that are not easily measured.

All fair points. And in the next article of this series, we’ll go through each and check. Fair warning once again, though: You may end up thinking differently.

In the meantime, don’t miss out on the other articles in this series:

- Brand Campaigns, Part 1: What Exactly Are They?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 2: Where Did They Come From?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 3: How Does Brand Advertising Work?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 4: Why and When Should You Use Them?

- Brand Campaigns, Part 5.2: Debunking Apple’s “Greatest Ad of All Time”

Cover image: Photology1971