Is there anything to learn from the success of Google, Facebook, Uber, or Didi (the Chinese equivalent that acquired the Uber brand in China) that can be applicable to any regular company? Besides the business principles underlying these companies that are commonly discussed and researched, there is little discussion about the branding positioning themes, themselves, that these new brands are investing in.

This article is an attempt at analyzing the underlying themes stemming from several local and international platform brand communications and initiatives in China. 2017 was a turning point in China’s global influence, which was seen reaching higher scales through geopolitical redistribution carried by the One Belt and One Road program and urban transformation initiatives such as Mobike (a bike sharing platform that started in China and is now active in several cities across Europe and Washington state in the US).

Platform Brands and the Economy

Platforms are a new type of firm. According to Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism, they are characterized by providing the infrastructure to intermediate between different user groups, displaying monopolistic tendencies driven by network effects, employing cross-subsidization to draw in different user groups, and having a well-designed core architecture that governs all interaction possibilities.

The recent writing Machine, Platform, Crowd from Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson connects the platform economy analysis with two important business trends: Artificial Intelligence (that questions the role of human labor in a relatively short future) and Crowd Resource [that we find in user-generated content (UGC) brands]. A combination of Platform, AI, and Crowd source already happens to be in place improving Google search and, more often than not, working in pair with platform businesses. These complementary business and technological innovations, along with new emerging technologies such as blockchains, are a powerful toolset for the creative exploration of future platform business ideas. Platforms are set to grow, with the effect of monopoly and public reaction against giants such as Google or Facebook possibly being the only threat to this development.

Hence, in light of this development, our urge to find out: What is there to learn from the success of platform brands?

Access to the technology may not be the only bottleneck, as cloud platforms are examples of on-demand technology that can be used by any company in combination with their own.

Therefore, it may not be about replicating business dynamics with technology alone, but more so about catching the cultural trend that these platforms are carving into the fabric of the economy.

Beyond the Economy, Platforms Are Establishing New Subcultures for Businesses

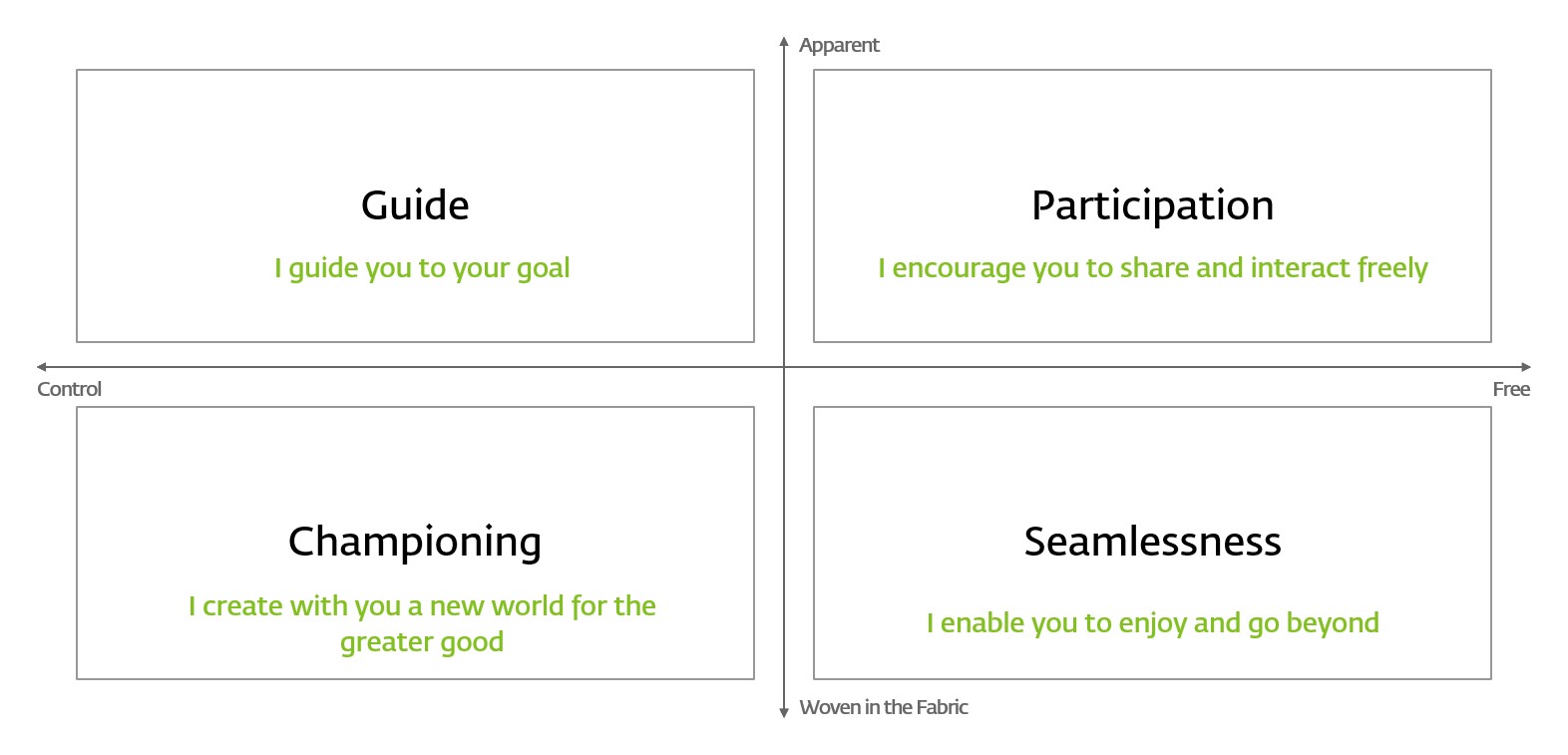

After a retrospective analysis of our experience with leading platform brands, we have identified 4 subcultures structuring the movement underpinning the development of today’s platform economy. These waves enable us to better tame than resist the fact that a platform tsunami is on its way. We invite brands to pick up ideas from it, ideas that can be leveraged in existing businesses with or without a technological shift.

1. The Guide Subculture

In this subculture, the platform acts as a guide or, in extreme cases, as a commander. In other words, the platform brand exerts control over users to follow established rules and steps. As stated before, it “governs interaction possibilities.” Its user interface is apparent and straightforward. Every single step is guided and precisely designed to lead us on paths created by the platform brand. Google’s search engine is the epitome of this subculture. From the first letter typed, Google shows a limited set of possible directions suggested by its big data. Results are well classified to form and strengthen our Internet search experience. It becomes a functional tool and our habitual search engine in life. Indeed, it is the synonym for search and reliability.

In fact, this subculture has been so well established that competitors such as Chinese Baidu and Microsoft Bing still feel compelled to follow the routes and user experience set by Google, as users feel awkward when they see something different from the industry standard they’ve been accustomed to.

Guiding interface platform brands go beyond emphasizing the benefits brought about by functionality. Recently, Tmall launched its new brand strategy, shifting its positioning from a ubiquitous shopping platform – Tmall Is Enough (上天猫就够了) – to the pursuit of an ideal lifestyle for different customer segments: Ideal Life, Go to Tmall (理想生活, 上天猫). Incorporating deep consumer understanding and insights, instead of directly selling products based on isolated functional needs, Tmall portrays several “living status models” for users to relate to and builds association of relevant product brands around. Through this soft yet guiding approach, Tmall regroups its user segments into Healthy lifestyle pursuer (乐活绿动), New single fabulous (独乐自在), Dare to be free (人设自由), Technology savvy (无微不智), and Amateur master (玩物立志), thereby creating a new set of rules for guiding activities around the platform. Besides reliability and usability across different scenarios, platform brands that are a step ahead communicate a sense of belonging by presetting consumer archetypes to lead users on planned routes throughout the platform.

2. The Stimulation Subculture

Most UGC-based platform brands are built on this ideology. Facebook, for example, encourages participation from users and presents itself as a space for others to interact in. It allows developers to produce apps, companies to create pages, and users to share information in a way that brings even more adoption, as long as they follow some fixed – yet generative – politics set by the platform brand.

The platform brand acts as a moderator, providing stimuli and tools that consistently encourage participant creation and production. UGC is presented via the platform brand’s framework and is organized to re-stimulate sharing and communication among its users. Chinese Douban, with its brand positioning of “Our Spiritual Corner” (我们的精神角落), creates spiritual belonging for different people that share a similar interest in a particular movie, music, book, DIY activity, hobby, etc., and provides stimulation for participation in everything from photography and travel to buying and selling goods in an online marketplace.

Connecting more people from different places is the driver of stimulating participation platform brands. However, with so much global content coming in from people with different values and interests, making it easier for others to understand, absorb, share, and recreate is a big task to accomplish. Streamlining information flow, simplifying participation steps, customizing content push, and grouping shared interests are all important in creating more user-friendly experiences. Moreover, a balance between individual freedom and non-interrupting organization is key to the success of stimulating participation platform brands. These are the fixed, yet generative, politics set by the platform brand. (Also, note that this positioning is not limited to UGC platform brands only.)

3. The Championing Subculture

These platforms, besides their apparent functional benefits, promote new ideals and calls for action to be delivered by users, thereby making each of us an agent in the creation of a new order – a different and enchanting new world.

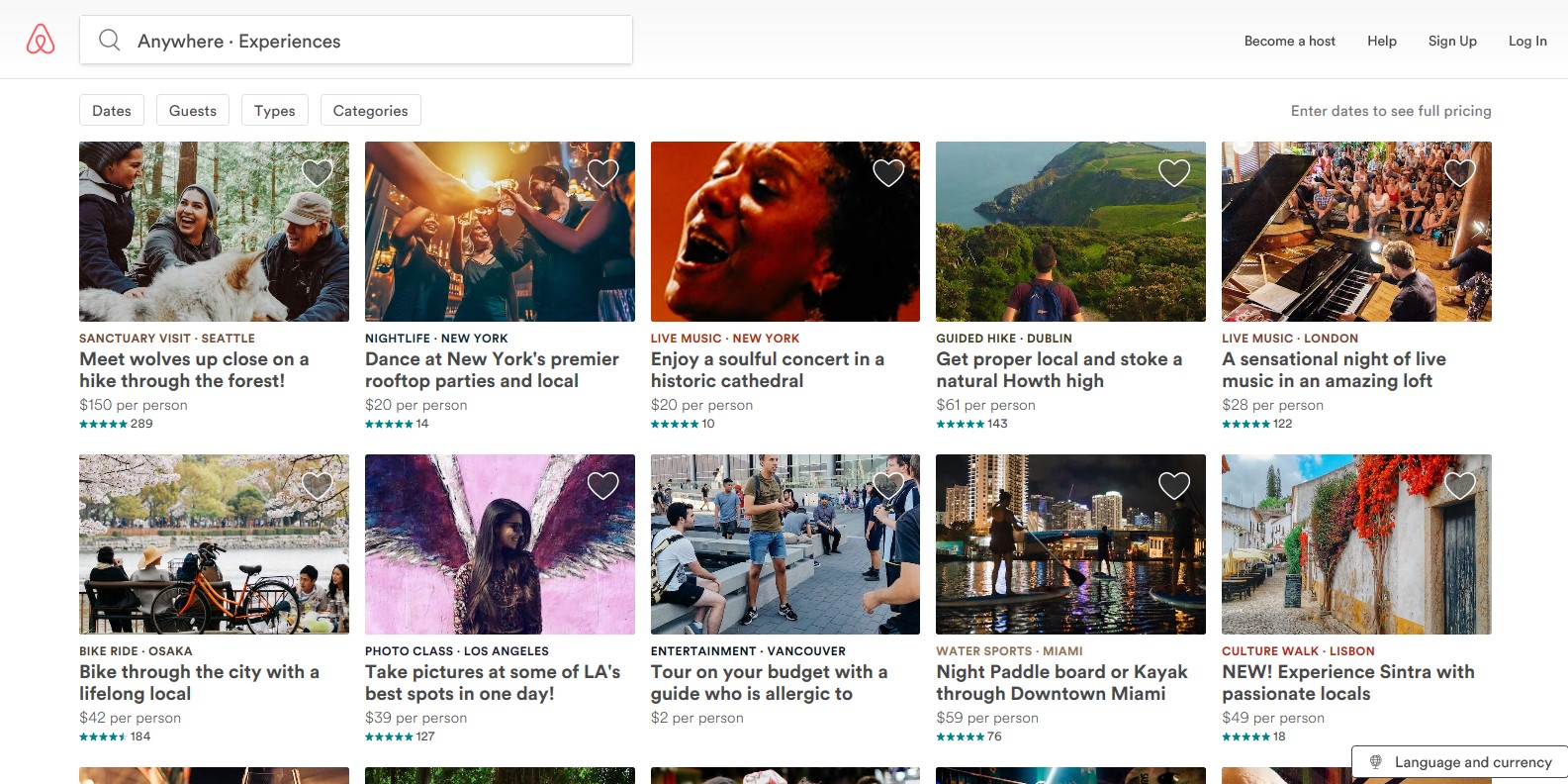

For example, Airbnb initially started by creating value in vacant rooms, connecting hosts with people looking for a value-for-money, short-term stay. Yet, Airbnb is also known as a hospitality industry disruptor and an advocate of the inspirational vision “Create a world where 7 billion people can belong anywhere.” As such, it goes beyond being a simple intermediary between tenants and domestic hosts to deliver a call to action for the world to view travel – and hospitality – in a new way. It aims to change the routines of the world and give a new set of responsibilities to its user groups by raising the stakes of what it means to be a host meeting travelers and creating experiences in the city. This is the meaning behind Airbnb’s recent Magic Trip initiative where unique, enchanting experiences are prepared and delivered by various user groups. Also, it gives Airbnb space to develop more services around the “live as a local” concept – services including introducing local dining, entertainment, destinations of interest, and more.

As Didi becomes the monopolistic mobility services platform in China, it has begun to deliver a brand message of “inviting all hailing companies to jointly develop better mobility solutions for people,” which suggests a tendency towards stimulating participation. The imagery used feels like a system: building integrating resources for the city is reminiscent of the responsibility shouldered by governments and its citizens.

4. The Seamlessness Subculture

While championing platform brands emphasize the changes they bring to the world out-loud, seamless intuition platform brands take the quiet and unnoticeable route of supporting customers’ lives with intuitive solutions (such as carefree, quality services) that deliver emotional benefits. This shifts the focus from what the platform offers or creates to an experience focused on life and people. Platform brands become invisible, immersing themselves into users’ daily lives and offering not only a user-friendly platform, but also a “living body” intertwined with its users. The brand’s duty extends from simply helping users “make it” to providing solutions that “make things better and more suitable for you.”

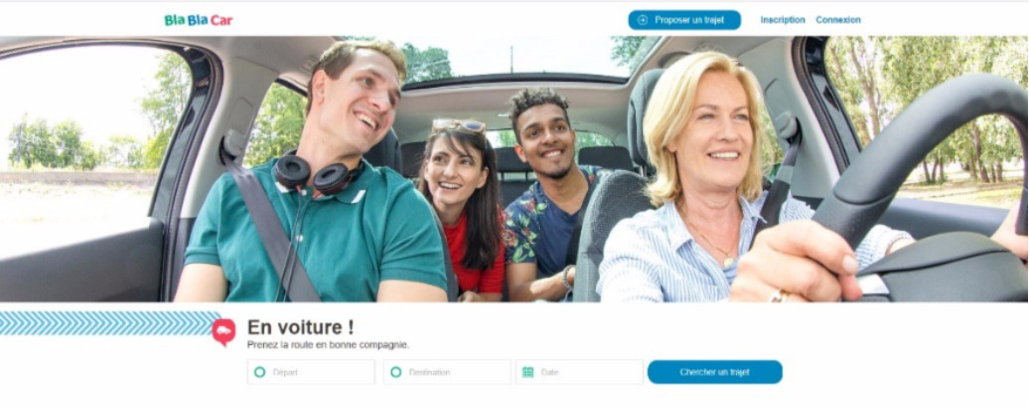

For example, BlaBlaCar and Didi communicate less on product offerings and more on emotional resonance, showing how much they care about delivering an enjoyable moment to users. No matter how bad users’ days are, these platform brands want their users to continue believing in a good quality of life.

Going further, platform brands are more than caretakers. The platform is not definitively important; the enriching experience, the enlightening adventure, and the positive possibilities that the platform brand enables are more relevant. For example, inspirational working hub WeWork positions itself as an enabler through its tagline “You are the creator of your life” (生活由你开创) in China’s market.

Conclusion: The 4 Positioning Spaces of Platform brands

A closer look at the different types of platforms brings to light surprising variety and adaptability: advertising (Google or Facebook), cloud (Amazon Web Services), industrial platforms that are revolutionizing factory production (GE), product-as-service platforms (Zipcar, Spotify), retail platforms (Tmall), and lean platforms that appear asset-less apart from their data ownership and control of the core architecture beneath user group interactions (Uber, Airbnb). Platforms have colonized the economy and are already ubiquitous.

The 4 positioning spaces identified have told us different success stories for platform brands. It provides direction for others to overcome common, negative perceptions surrounding monopolies (driven by network effects), and governs interaction options as platform brands access an increasing number of activities across different categories. And, for regular companies, this provides inspiring themes for innovation.

- Guide – “I guide you to your goal.”

- Stimulation – “I encourage you to share and interact freely.”

- Championing– “I create with you a new world for the greater good.”

- Seamlessness – “I enable you to enjoy and go beyond.”

Platform brands are shifting the focus from what platforms offer to what helps make the experience better. Target audiences become the center of brand positioning; platform brands comfort, facilitate, and empower users to enjoy a better mood, indulge in more special moments, and achieve more – all while being less visible and woven in the fabric.

Cover image source: Martin Reisch